Carving Up the TPU

Leftovers for Jensen or Just Gravy on the AI Trade?

The first words of our August State of the Themes AI section were direct: Long GOOGL.

We elaborated…

OpenAI is compute-constrained. Without their own datacenters or their own chips, they are at significant disadvantage to Google, which not only is an ascendant hyperscaler but also a chip designer that has designed the only mass produced chip competitive with Nvidia’s core offering across many metrics and has optimized their entire research, training and inference pipelines for it [...]

Google has low customer acquisition costs, best-in-class first party data, full vertical integration and TPUs enabling cheaper training [...]

It’s clear that both the technical and market tailwinds favor Google, but the market does not seem to be pricing that in.

While the writing has been on the wall for some time, the market’s perception of Google has dramatically reversed over the past several months – transforming from an AI loser bleeding its search dominance to a stalking horse destined to undercut the most consensus AI winners.

We can see this shift occurred around the time we wrote up Google (or, perhaps, around the time the legal overhang lessened) on this chart from Coatue:

This sentiment has only accelerated in the past week with the release of Gemini 3. Not only is Google now firmly positioned at the cutting edge of frontier models, but it’s doing it on its own terms, or TPUs. It is indeed possible to train a frontier model without NVDA... that is, if you’re an ML-pioneering hyperscaler who has spent the past 10 years developing and optimizing for this custom silicon.

The announcements that both Anthropic and Meta are planning to implement TPU chips raise further questions about NVDA’s dominance. Surprisingly, META reportedly wants TPUs for training, not just inference. None of this information is truly new (see above) but the one-two punch, combined with growing skepticism of OpenAI seems to have culminated in a passing of the public torch.

While we are happy that the market has caught up to the trade – Google remains our largest allocation in our Dynamic AI basket – we are also wary of over-extrapolation, recency bias, and consensus crowding. After all, as Oracle has shown, you can go from a 40% gap up to CDS watching in a matter of weeks.

Is Google’s vertical integration both a cost and structural advantage? Is the CUDA moat shrinking? Are NVIDIA margins at risk?

Perhaps.

But maybe there are two ways to think about this:

Switching costs for architecture/ecosystem is high for AI accelerators. Gemini 3 should be bullish for compute demand as labs locked into NVDA rush to buy more of the next gen chips to compete.

NVDA’s margins are so high that any competitive threat must be aggressively priced in even if it means higher volumes.

In other words, isn’t a breakthrough model broadly bullish?

The market is clearly leaning on the #2, but we could find ourselves tempted to dip back into NVDA if sentiment overshoots reality. Regardless – if a TPU scale-up is on the horizon, who else stands to benefit?

First, we will run through some technical details, then highlight where we think the broader “TPU trade” goes from here.

TPUs for Idiots

At its core, a neural net is just a machine for doing enormous numbers of weighted sums. For myself (an investor, not an AI engineer), I find it useful to reduce neural nets to:

Inputs x Weights = Outputs

Inputs are arranged as a matrix (a batch of tokens, images, whatever). Weights for a layer are another matrix. Take a simple example: handwritten digit recognition. A 28x28 grayscale image is 784 numbers - the “8-detector” neuron holds 784 weights (28x28). For that individual neuron, the core operation is multiplying each pixel by its weight, adding everything up, and then finally comparing the score against other digits.

Once you scale this up to our modern AI/ML models you’re doing trillions of these “matrix multiplication” (abbreviated as matmul) operations – in effect, a bundled batch of all those weighted sums.

Enter: CPUs, GPUs, TPUs.

A CPU is like one very smart and capable worker – good at anything but slow at repetitive jobs. A GPU is like thousands of generalized workers. A TPU is like an automated factory line built specifically for one task, with the machines arranged so the work has almost no back and forth.

It’s important to recognize that even within the AI/ML space, different functions require different chips. Google itself publishes the following guide for how to choose chips depending on the task at hand.

As we laid out in Interconnects 101, the layman’s understanding of the difference between a CPU and GPU is that a CPU is built with a relatively small number of cores, but with each of those cores capable of executing hundreds of specific instructions over dozens of units. Consumer CPUs generally have up to 16 cores with data center chips up to 128 but even with significantly higher clock speeds, this is no match for the parallelization that GPUs allow.

What we think of as a ‘core’ in a GPU is known as a streaming multiprocessor (SM) in Nvidia-parlence. Rather than focusing all of the core’s resources on routing instructions through specialized units, GPU SMs leverage dozens or hundreds of copies of the same units simultaneously. For example, Nvidia’s Blackwell architecture SMs each have 4 “tensor cores” and 128 “CUDA cores” for a B200 with 192 SMs, that totals 768 and 24,576 physical cores respectively.

Though not comparable on a core-to-core basis, TPUs take this philosophy to the next level and dedicate nearly the entire silicon area to crunching matmuls. They can do this because cores aren’t instructed in the traditional sense, but data is drawn through them more like an assembly line than a laboratory.

The architectural driver behind the TPU is the systolic array. Though reports differ on the size and arrangement of the array across TPU versions, the philosophical departure from GPU SMs is consistent.

The array is made up of MAC cells, short for multiply-accumulate, which Google describes as ALUs (arithmetic logic unit) which is a classic computing building block. The difference is that MAC cells are ALUs that don’t accept instructions, just data. They don’t have to choose between FMA, ADD, SHIFT, or any other of hundreds of possible instructions that a less specialized processor might see – they just multiply and accumulate. This saves on space by eliminating unit-level instruction caches while also essentially eliminating data caches as data flows through the array in a predetermined fashion and saves on power by pushing utilizations to the max.

This is why TPUs can offer very high performance per watt and per dollar on machine learning, but are essentially useless outside that domain. You get extremely high throughput on the kind of linear algebra that defines neural nets which means lower power per operation and a smaller die area for a given level of ML performance. However, this comes at the price of much less flexibility than a GPU.

Google has made Gemini’s per-prompt footprint a PR point, so Gemini likely has a real advantage in energy per text call – helped by TPUs and their own tuning – but there is no transparent or quantified comparison for the training runs. Inference, at least, looks to be much more energy efficient per user interaction on TPUs.

In short, the TPUs are hyper-specialized ML chips that sacrifice flexibility for efficiency. But as AI increasingly moves to the “mass-production” phase, even small efficiency gains can prove very meaningful.

What Does it Mean for NVDA

We’ve been wary of the competitive risks from ASICs to Nvidia for a while (and a TPU is in fact an ASIC). But we’re also wary of headlines that declare Nvidia dead. If our own DeepSeek coverage taught us anything, it’s that the easiest way to move the US stock market (which is a KPI for many financial media outlets) is to target Nvidia.

As we’re indifferent to moving the market and more focused on what happens over the long term, we’re trying to minimize sensationalism.

One key thing to emphasize is that switching from GPUs to TPUs means learning a new language – i.e. switching ML frameworks from PyTorch to JAX. Switching software environments is a significant task – non-trivial, disruptive and expensive. After all, the first TPU was created by Google back in 2015, and the giant has spent the last ten years developing internal workflow, physical infrastructure and model architecture around it. For others, particularly smaller players, the learning curve will be far steeper.

However, Nvidia’s silicon stranglehold and pricing power does provide a material incentive to at least attempt to diversify. Anecdotally, OpenAI has been trying to build an internal JAX equivalent for the last year – newer startups deciding to build initially on JAX rather than PyTorch can result in new “locked-in” users. Moves by Meta and Antrophic demonstrate that major players are indeed seeking silicon diversity.

But the reality is that CUDA and PyTorch are still dominant today and will probably mean that Nvidia will continue to see strong demand in the near term regardless of Google’s plans for TPUs (i.e. whether they sell, rent, or keep it as a walled garden). Keep in mind, despite its use of TPUs, Google is still one of NVDA’s largest customers.

We can certainly understand the market’s sensitivity to any risk that might jeopardize NVDA’s competitive dominance – even if it doesn’t materialize until 27/28. It isn’t surprising that the kneejerk reaction was for NVDA to trade lower. Still, it should be understood as a reaction to the potential of future risks – and future risks to margins, not to volumes. The market is not valuing Nvidia on what happens in 2026, and Nvidia’s margins are (historically speaking) unsustainable over the long term. As seen in the reaction to NVDA’s great earnings last week, the market cares much more about what things look like in five years than what they look like in six months.

Right now, NVDA is still able to deliver volume into a tight market, and overall we view this TPU development as much more positive for GOOGL than it is bearish for NVDA – in fact, we don’t really think this specifically is bearish for NVDA or their supply chain.

Rather it’s probably quite bullish for the supply chain. Both Google and Nvidia are going to be fighting for the exact same CoWoS capacity at TSMC, which will remain the rate limiting factor.

To recap:

Gemini’s success reinvigorates model competition - reinforcing broad demand for compute, which is still dominated by NVDA

CUDA/PyTorch is still a major switching cost, and Google’s success on TPU may not be as easily replicable for third parties

Both supply and infrastructure bottlenecks, not demand, is the key bottleneck today

Will Google Sell TPUs?

Another open question is Google’s TPU distribution strategy:

Do they keep TPUs for themselves as a competitive advantage?

Do they rent out TPUs (which they do already, via GCP)?

Do they become a merchant TPU vendor and alternative to Nvidia?

The first alternative – full in-house proprietary advantage – risks under-monetizing an incredibly valuable asset (remember, NVDA is worth more than GOOGL today) and has already been contradicted by chip sales to Anthropic, Meta, and Fluidstack.

In the second alternative – the “cloud route” – Google is limited by both TSMC capacity and the physical availability of their own data centers. Here, they may maintain ongoing cloud revenue, but are still both committed to and constrained by infrastructure.

However, if Google decides to become a selective merchant vendor (shipping TPUs into neoclouds, sovereigns and selective hyperscaler datacenters i.e. META) they would generate revenue and gain presence without committing to infrastructure. In a world where stocks get hit every six months on capex fears, this might be a good way of hedging. Data center and power capex is very long-duration and hard to unwind. By contrast, selling TPUs is essentially a pure margin game with variable production that can be ratcheted down. This shifts risk and produces optionality, making Google harder to kill.

In a somewhat reflexive way, we think the market’s reaction here is going to force Google to sell TPUs. If they don’t break out TPUs as merchant revenue and data center/power constraints cap GCP capacity growth, then the narrative will become a refusal to monetize the silicon while being subjected to an infrastructure bottleneck they do not control.

Further, if Google does not sell TPUs, they will end up creating space for a new merchant silicon threat in the medium term (think 4-7 years). It would be much better to broadly distribute TPUs and gain the telemetry advantage rather than risk this business going to a competitor (especially a Chinese one).

Back in September, it was reported that Google approached Crusoe, Coreweave (CRWV US) and Fluidstack to give them access to TPUs. Fluidstack, for example, has a deal where it deploys TPUs in a Terawulf (WULF US) leased data center in NYC – with Google providing a $3.2 billion backstop and taking 14% equity. In doing so, they’re using the “franchise” model versus the “merchant” model (you find the power and build the shell, we will drop in our TPUs). Furthermore, this week, we saw headlines about Meta (META US) buying TPUs from Google. Meta has its own silicon (MTIA), but if Google offers TPUs at a better price/performance ratio for serving Llama models, Meta is rational enough to use them.

In short, we believe the decision has largely already been made to begin selling TPUs.

So, what’s the trade?

First-Order Beneficiaries

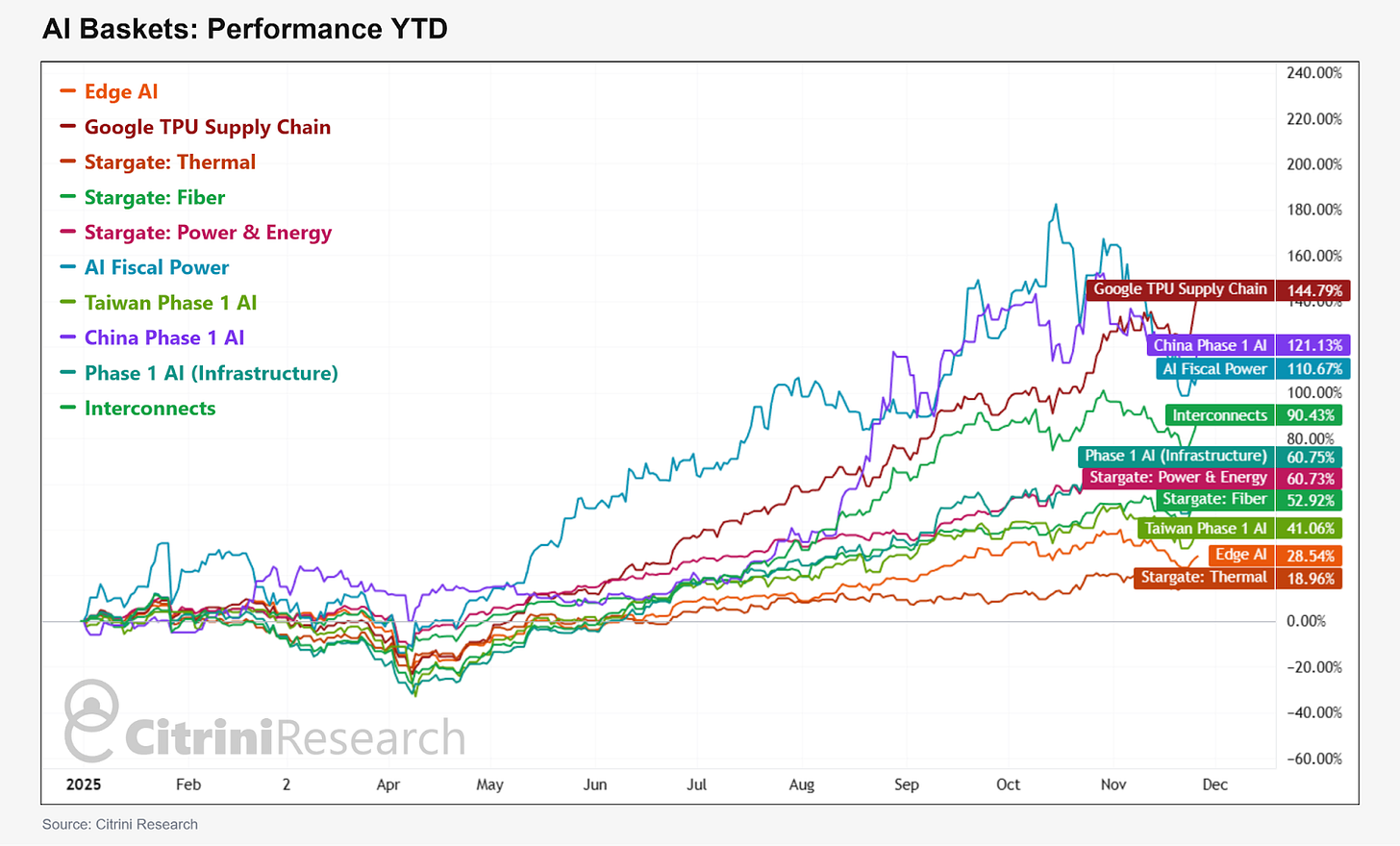

Comparing an equally weighted basket of our 25 highest-confidence TPU suppliers to our broad 125-name Phase 1 AI Infrastructure basket, we can see that they’ve taken off recently in relative terms:

Across the various AI categories we track with our baskets, these direct TPU suppliers have been the best performing group YTD with the majority of that outperformance beginning around August:

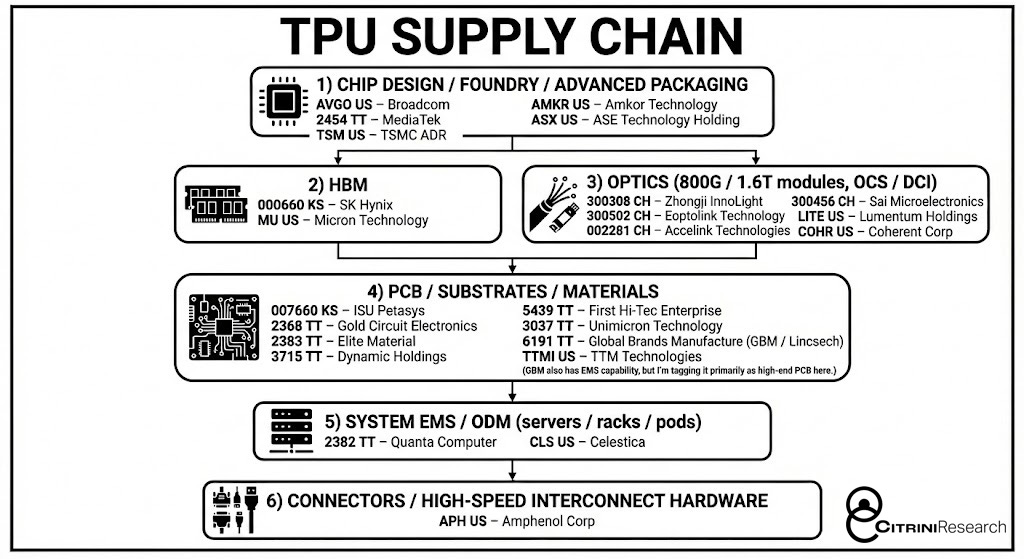

Here’s the list of names we are looking at as TPU suppliers. We’ve been relatively picky in this list, and have left out some names that have been mentioned in association with TPUs but for whom the relationship seems less clear or direct.

View our equally weighted TPU Supply Chain basket on our portal here.

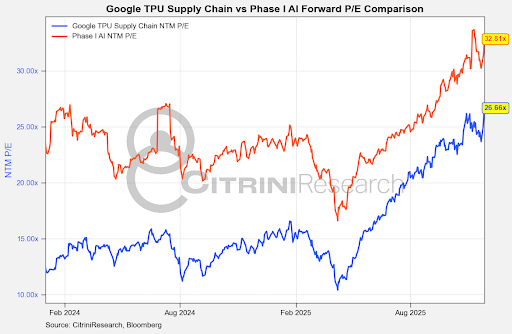

As a basket, these names still trade cheaper on average than our broader Phase 1 AI infrastructure basket that is heavily tilted towards GPUs. Some of this is due to the more cyclical nature of a lot of these suppliers, but if increased TPU demand drives a sustained upcycle in advanced PCBs, substrates, and high-speed networking boards (and their upstream suppliers in copper foil, resins and specialty laminates) we could continue to see a re-rating.

One thing to emphasize, though, is that there’s a huge amount of overlap in the NVDA and GOOGL supply chain – and the same overall capacity constraints haven’t changed. To the extent that two giants are competing for the same production capacity, it should benefit the pricing and bargaining power of these supply chain players.

We like the upside for names in advanced packaging – the obvious being TSMC (TSM US), but also ASE (3711 TT) and Amkor (AMKR US). These should do well as competition heats up. Memory (HBM) remains the bottleneck, with SK Hynix (000660), Samsung (005930 KS) and Micron (MU US) supplying memory (in that order).

We also think this could provide a catch-up impetus for Mediatek (2454 TT) – a name that seems to be well positioned from a markets perspective having participated in very little “AI” upside over the past year due to poor performance in mobile.

Focusing on the key differences in suppliers for TPUs and GPUs leads us to a few conclusions for our basket. First, TPU boards are denser with proprietary interconnect routing, benefiting niche high-end PCB makers such as Isu Petasys (007660 KS), TTM Technologies (TTMI US) and Unimicron (3037 TT). NVIDIA boards are also complex but follow a more standardized form factor (OAM/UBB).

Second, we see benefits for pluggable optical transceivers. Unlike GPUs that use electrical packet switches (InfiniBand/Ethernet) for this layer, Google uses MEMS-based optical mirrors to physically redirect light (called OCS or Optical Circuit Switches). This eliminates the need for power-hungry electrical transceivers at the switch level. Google has increasingly partnered with Lumentum (LITE US) to mass-produce these switches (specifically the Lumentum R300 and newer R64 series). While Lumentum designs the system, the actual MEMS mirror chips are often fabricated by Silex Microsystems, a pure-play MEMS foundry owned by Sai MicroElectronics (300456 CH). Also, while Lumentum supplies the MEMS mirrors for Google’s internal OCS (Project Apollo), GOOGL is driving the OCP (Open Compute Project) standard for OCS to wider adoption. Huber+Suhner (HUBN SW) is the other critical player in this niche.

Some other names worth an honorable mention as well are:

Alchip (3661 TT) which was mentioned alongside Mediatek in a TrendForce write-up on Trillium in chip design but has no incremental headlines since, and is additionally tied to AWS (Inferentia/Trainium) rather than Google

Global Unichip (3443 TT) is the likely backend design partner for Axion - Google’s custom ARM-based CPU that will be utilized instead of Intel Xeons

Jabil (JBL US) and Flex (FLEX US) in System EMS which were mentioned in a secondary source Taiwanese supply chain piece but did not have the same level of confirmation as Celestica

Panasonic (6752 JP) and Furukawa (5801 JP) which were mentioned in that same piece but also lacked confirmation.

Monolithic Power (MPWR US) has been gaining share in the 48V server rack architecture for Google’s TPUs. There are also names which deal with aspects like the Liquid Cooling (Deschutes CDU and Cold-plate Loop) - the clearest direct manufacturing partner being Boyd, who sold its thermal management segment to Eaton (ETN US) recently. Still, these are broader and other players have compatible solutions that would work with TPUs.

Second-Order Winners

Who else might materially benefit from the proliferation of TPUs and Gemini 3 becoming a viable state-of-the-art model?

Apple: A Google AI Customer?

Somewhat surprisingly, one of the biggest indirect winners might be Apple (AAPL US), who may see its patience and discipline pay off with the compute platform of their dreams. Apple and Google already have a strong working relationship, so competitive dynamics shouldn’t preclude their collaboration here.

From a product philosophy standpoint, Apple and Google are already converging on a few shared ground-truths: first, that reducing round-trip latency and jitter is imperative to user experience. This most notably manifests itself as lagging Siri, spotty chat-bots, or frozen applications. Second, both Apple and Google are, for lack of a better term, control freaks. While both experiment, neither is remotely comfortable with the unpredictability of truly dynamic LLM inference… remember the debut of Google Search’s AI features?

Both of these issues can be solved in one fell swoop by leveraging the static determinism of a TPU pod’s systolic array. If Apple wants to position Siri as a fast, reliable, transactional personal assistant rather than a superintelligent, conversational chatbot, TPUs offer a perfect engine for nearly any workload that can’t be run locally. While Apple has made great strides in reducing barriers to local inference on mobile devices – security features like FaceID will never be offloaded for example – much of the token volume that Siri and Apple Intelligence will handle is likely to require quick, cheap cloud-based inference using information straight from the web, which you may have heard is another Google specialty.

Even if Apple wanted to maintain a fully closed loop here, they would still need to incorporate external information for requests like sports scores, restaurant reviews, or thousands of other everyday requests and Google just happens to have the best of both. Apple isn’t locked in to Nvidia’s ecosystem to the same degree that others are, and Google ramping Gemini might be the path to finally getting a Siri that doesn’t suck.

SiTime and MACOM

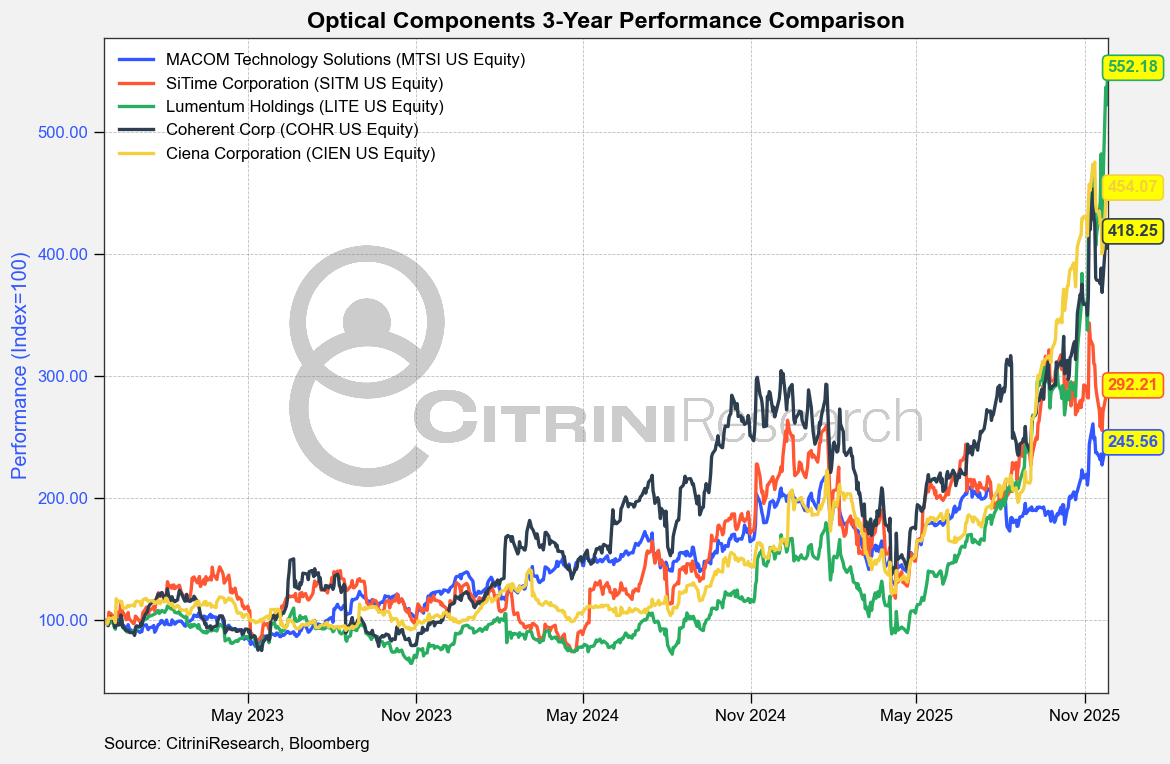

In our July 2024 article Can You Hear Me Now? Telco Suppliers New Dawn and the Coming Optics Shortage, we highlighted Lumentum (LITE US), Ciena (CIEN US) and Coherent (COHR US) as big winners of optical demand. There’s been a renewed focus on optics demand amidst the TPU take frenzy for good reason. Google’s internal TPU forecast for the next cycle has been revised from ~2 million units to ~4 million.

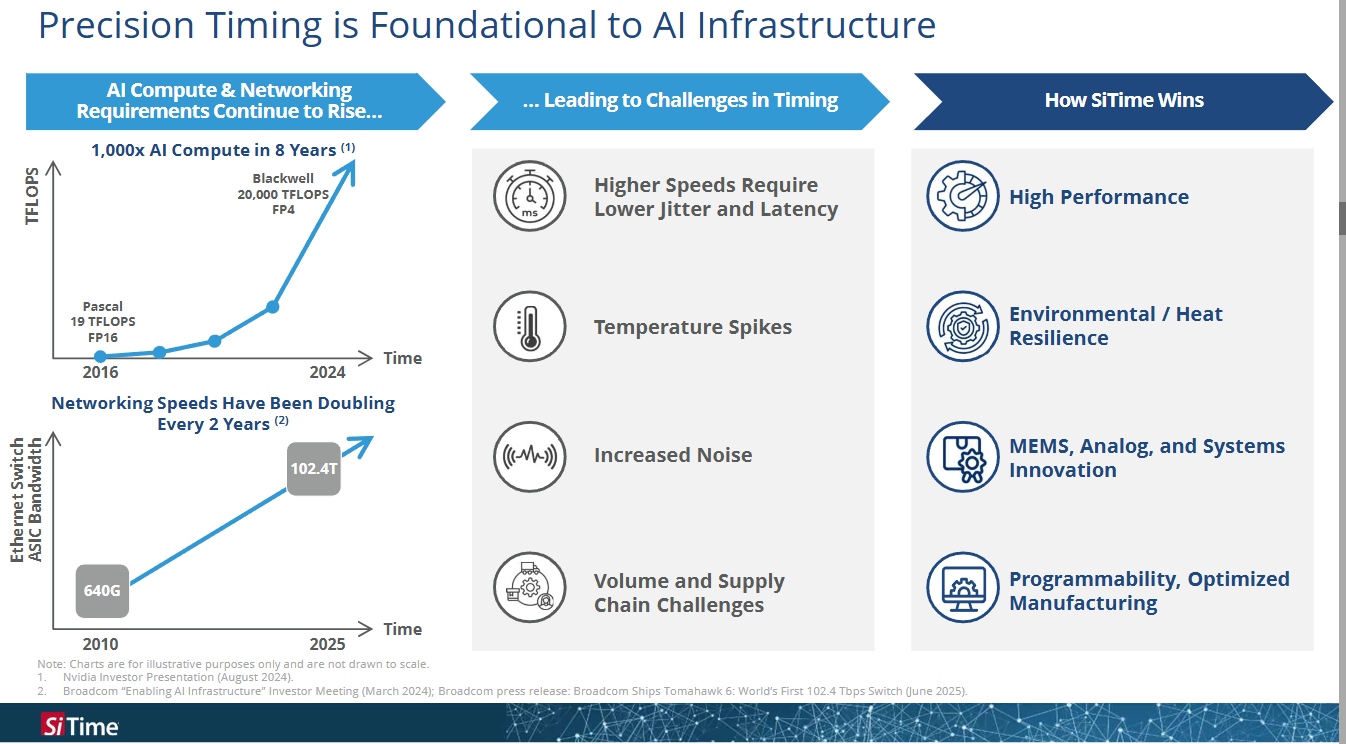

That step-up in TPU V7 servers is being viewed as a key driver behind a jump in 1.6T optical module demand from roughly 3 million modules in 2025 to ~20 million in 2026, with Google alone consuming between 6-10 million of those via TPU V7 racks.

We do think there’s a real risk to the lazy long who just says “more TPUs = linear growth in optical modules”. Bandwidth efficiency could end up being a genuine headwind to a naive links per GPU/TPU model. We think it’s important to focus on where the odds of capturing the next rate transition are much higher related to expectations. Our read is simple: TPUs shift bandwidth.

Google can flatten pods and keep more traffic local, but the surviving links still need to jump from 800G to 1.6T to keep panel counts, thermals and power budgets under control. The chip count is also compounding fast enough that total endpoints rise even if links per unit fall. Inside the rack, short-reach copper and linear architectures carry part of the load, which changes the product mix but not the opportunity set for two names we like.

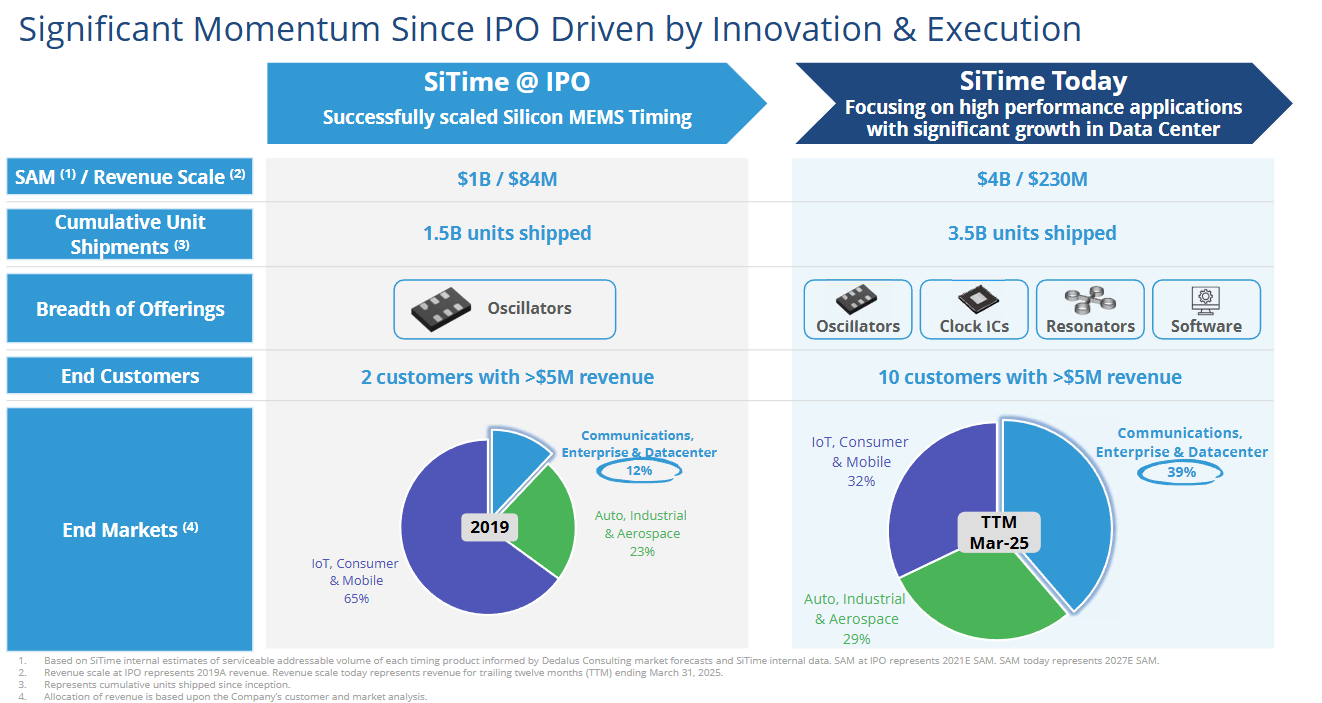

We came across these companies that aren’t directly in the TPU supply chain but could ultimately do quite well in their slipstream – SiTime (SITM US) and Macom (MTSI US).

SiTime sells the timing layer that every high-speed system depends on: oscillators, clocks and synchronizers that live inside 1.6T modules, NICs, switches and accelerator boards. Macom sits in a similar structural position on the photonics and copper side. Their products aren’t tied to one architecture; they follow the rate transition itself. If AI operators use 1.6T pluggables, then MACOM ships 200G photodiodes, TIAs and drivers. If they push traffic onto short-reach copper, MACOM ships linear equalizers and reach-extension silicon. If they experiment with near-packaged optics, MACOM sells the same photonic front end into that form factor.

SiTime will see their MEMS oscillator content in a 1.6T optical module close to double (to about 2 dollars per module), and Macom maintains >60 percent share in the 200G photodiodes used in those same 1.6T modules. Both of these companies posted beat and raise quarters, with stronger revenue and margin expansion. MACOM’s 200G per lane products will see a significant ramp in 2026, along with their photonics products.

Since the AI trade kicked off in earnest, SiTime has lagged in performance relative to Coherent, Lumentum, and Ciena due to their exposure to IoT and mobile.

They don’t operate in the most sexy niche – after all “precision timing” doesn’t really have the same draw as “AI Accelerator”, but they are pretty much the only player in this space.

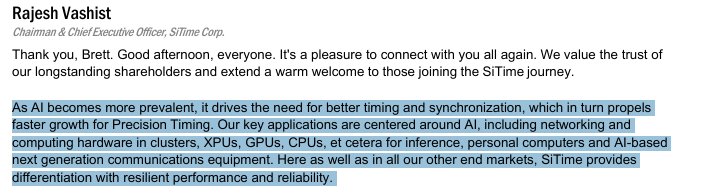

Over the past five years, SITM has become a much more diversified company. While IoT, Consumer & Mobile still make up a significant portion of their revenue, Communications, Enterprise & Datacenter (CED) has more than tripled.

The CED segment is set to make up almost half of its revenue, and the company is guiding to $100-103 million in Q4 revenue with around 60% gross margin. This implies an exit revenue run-rate above $400 million annually - driven heavily by AI infrastructure. It’s an entirely reasonable assumption that CED/AI revenue compounds at something like 30% annually over the next three to four years (as hyperscalers keep building out AI capacity) and as SiTime increases content per rack through products like SiT5977 and TimeFabric.

As we mentioned earlier, TPUs use OCS rather than DSP retimers – if the entirety of NVDA GPU volume became TPU volume it would likely be negative for SITM. Since we don’t see that happening, we see the higher demand for high speed optical modules being an overall net positive.

This renewed focus on 1.6T could not come at a better time to position here – the recent market volatility saw SITM’s shares drastically appreciate following earnings and then sell-off on little more than beta. SITM reported a blow-out quarter, with revenue up 45% YoY, expanding gross margins and EPS more than doubling.

Rough back of the napkin math: estimating ~20M 1.6T optical module units in 26 with $2 content per module, gets us to ~$40M of MEMS timing TAM in 2026 purely from 1.6T modules. SiTime is likely to secure between 25-50% of this. While these aren’t heroic numbers compared the whole company, consider this is just one socket in the AI rack, it’s driven by a specific, visible product cycle and it is incremental to their timing content in NICs, switches, routers, baseboards and other accelerators.

The company has cited multiple times the demand for their oscillators in increasing GPU efficiency and lowering latency. On the opportunity for 1.6T, they said:

“For example, optical module bandwidth is doubling to the 1.6 terabit level and these new modules are beginning to ramp now. Demand for the 1.6 terabit modules has recently doubled, indicating a sharp transition to 1.6 terabit technology in first-half 2026. Additionally, SiTime’s oscillator ASPs in this application are higher because of the higher frequency and performance requirements.”

If the first bull-case for SITM is the move from 800G to 1.6T optics in AI data centers being pulled forward by Google’s TPU build-out, where SITM’s oscillator content per module roughly doubles, the second is much more firmly in the tail. As we mentioned earlier, SITM has failed to keep up with peers primarily due to the tough handset environment and their still-significant mobile segment. As Apple begins to integrate with Google to improve AI, we’ll likely begin to see more investor focus for inference-on-device (see our memo here) and AI-centric wearables. Similar to our expectation that ASICs end up taking up more share of the AI Accelerator market, our view on AI devices has taken a bit longer to play out. Still, we would not be surprised to see that it is dominating the discussions on AI hardware towards the end of next year.

What does that look like? While data centers will continue to train and host large models, handsets, watches, medical devices and other wearables will increasingly run distilled, on-device models. These edge devices need very small, low-power, highly stable timing components that can live inside the RF front end, radios, and sensor hubs without blowing the power budget.

SITM is firmly in that world today. Apple has chosen SiTime as the exclusive supplier of MEMS oscillators for its in-house 5G modem, which should translate to ~$240M of revenue in 2027 just from that modem win. Their Symphonic integrated clock is another vector of growth in AI wearables – collapsing multiple clocks into a single, low-jitter, low-power device. That will become increasingly important for battery-constrained AI endpoints (think earbuds doing on-device translation, watches doing health inference or medical patches doing anomaly detection).

On-device AI will drive a new set of constraints: always-on sensing, local neural nets, real-time sensor fusion (for glasses and AR devices) and continuous-learning. Lower power despite more complexity has been a crucial pathway to outperformance in the AI complex, and it will only be increasingly important in the AI device complex.

In late 26-27, they’ll begin recognizing revenue from their new resonator Titan. This is the first time the company has gone below its oscillator products and targeted replacing the quartz resonator itself. Titan is a chip-scale MEMS resonator, with the smallest timing device footprint (~0.46mm x 0.46mm), ~50% lower power, 3x faster startup and stability across temperatures.

Conclusion

We are still on cautious footing into the end of the year (we’ve reduced from +100% net long to +80% net long and significantly hedged, while planning to raise more cash). However, keeping track of the implications of the AI accelerator market and general data center capex will continue to be important regardless of the macro-gyrations of the market and give us a good list of names to buy in any further volatility.

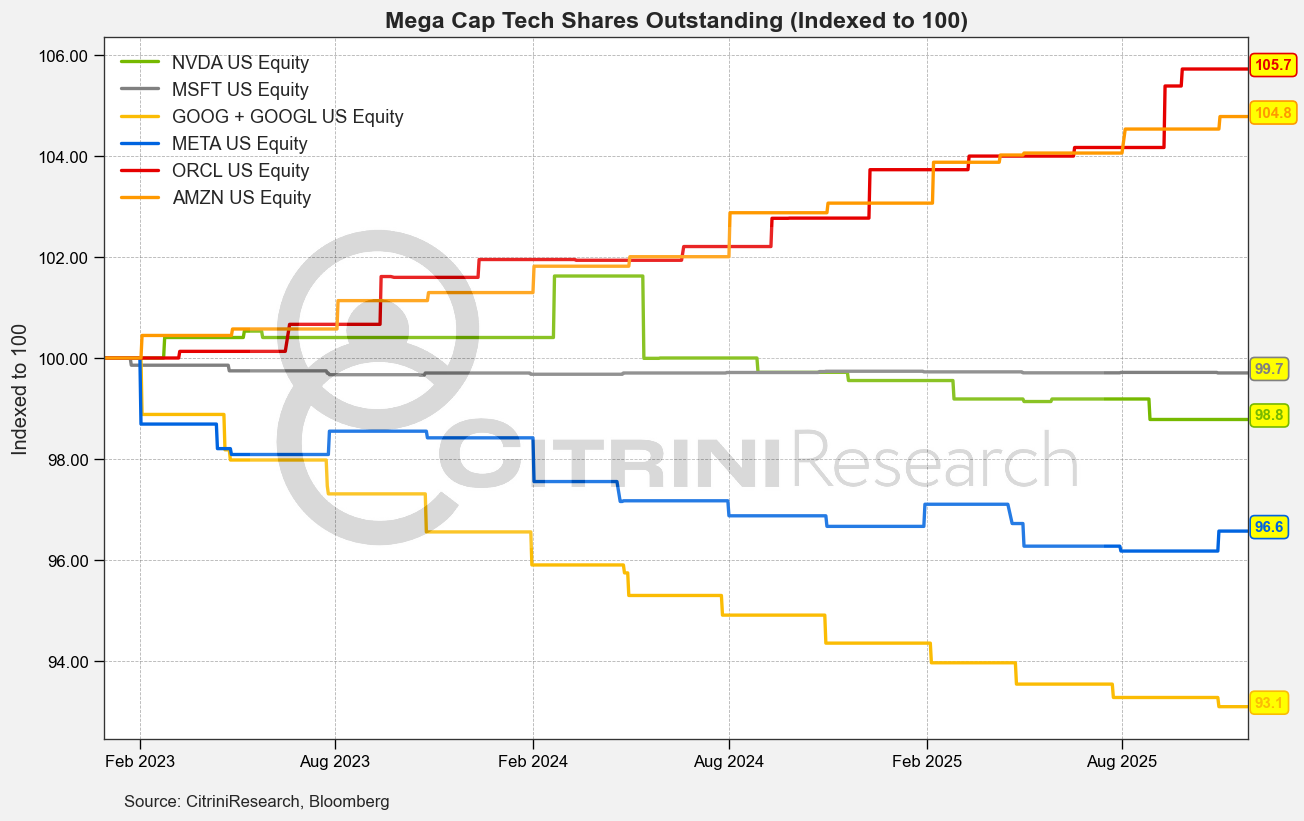

One point we’ve heard on the bearish side is the concern around MAG7 cash flow going towards capex rather than buybacks. As shown below, share count reductions have slowed or reversed for much of big-tech. To be fair, some degree of this has been offset by Nvidia’s own increased buybacks.

To the extent that these companies have a low cost of capital and believe in the ROI of AI capex, they will be less focused on returning shareholder capital. AMZN and ORCL shares outstanding have climbed, while MSFT is maintaining buybacks at a level that’s just enough to offset stock-based compensation.

Google and Nvidia have kept pace with buybacks since the AI capex craze kicked off, but with Google potentially ramping up capex on TPUs and Nvidia having to reinvest more capital to compete with them, it’s possible that we could see a simultaneous erosion of Free Cash Flow (FCF) for both parties and a structural contraction in shareholder yield. In short, the industry at large is shifting from a high-margin ecosystem to a capital-heavy utility model where cash is trapped in silicon rather than returned to shareholders.

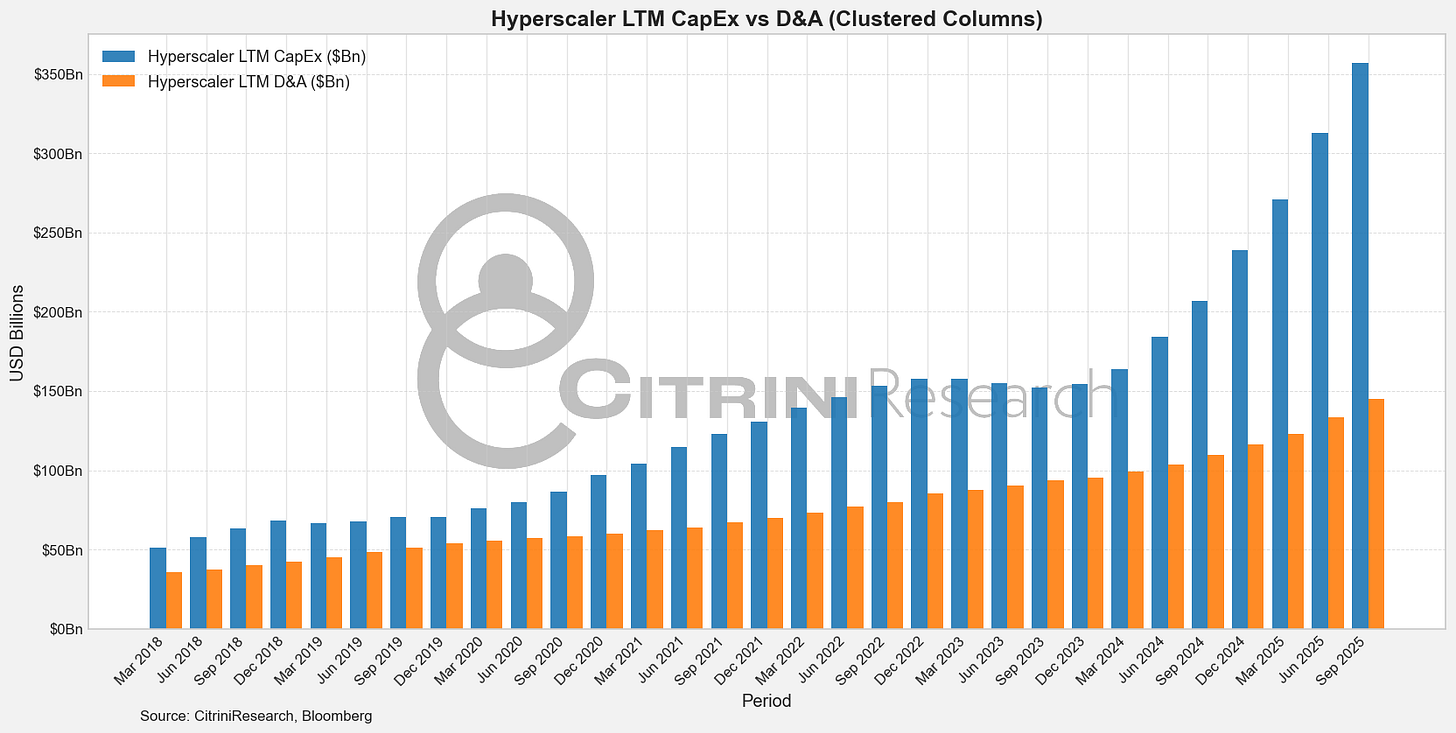

Further, the sheer pace of capex acceleration does mechanically result in an overstatement of earnings relative to cash flow. Usually we can ignore these sort of accounting discrepancies as rounding errors, but over the past twelve months the gap between hyperscaler capex and D&A has exploded to over $200 billion – a material portion of the entire market’s earnings.

We flag this as a point to watch. We don’t think it’s something that will drive markets currently, but we could see the narrative forming in a downturn.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t flag that it seems Jensen has gotten really, really concerned about Nvidia’s share price. See NVDA’s very odd tweet about Google:

And Nvidia taking the time to address 20 different bear theses in a communique…

…is just kind of weird. I’m used to small cap companies being very bothered by short theses but not the largest company in the world.

We will continue to position for the changing dynamics of the industry while also recognizing the potential risk of a broader reset in expectations.

I see you intentionally left out Broadcom.

Great piece, would just add 2 things: First, the (fairly obvious) fact that Gemini taking marketshare at the model level alone will create massive TPU demand, and that probably gives this basket a margin of safety. Second, JAX is open source, so very much like android, it will attract OEMs to invest in the ecosystem.