Zoltan Pozsar: Confidently Incorrect

Misleading information masquerading as expertise

Zoltan Pozsar: Confidently Incorrect

“No neon, no chips.”Zoltan Pozsar, either lying or being woefully uniformed

Zoltan Pozsar, Credit Suisse’s Global Head of Short Term Interest Rate Strategy, has recently released a letter titled “Commodity Chokepoints and QT”1 in which he states that there will be a neon shortage that severely affects the semiconductor industry, that the military demand for chips will push consumers out of the picture and finally, in the most egregiously diminutive and terribly misinformed take, implies that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was motivated by a desire to secure neon production capabilities…it’s bad. It’s really bad, because it’s not just wrong but it’s hyperbolically wrong - inducing panic over an already uncertain situation that requires none be added. In the article below, I’m going to tell you why Neon is important for semiconductors, why the market for it is already tight, why the invasion of Ukraine will have little to no impact on this fact and, finally, why - far from being the reason for the invasion in the first place - neon has essentially zero impact in the motivations for warfare here.

The Basics:

Among all, today the most important use for neon is in ultraviolet (UV) lasers, called excimer lasers. The term excimer is a short for excited dimer. This can make clean and precise cuts in the range of hundreds of nanometres. UV lasers produce no heat, meaning it does not cause scarring or risk burning the material it is used on which makes it popular in laser eye surgery (LASIK).

Neon is used in the lithography process of semiconductor fabrication, specifically in argon-fluorine excimer pulsed lasers (ArF lasers). In semiconductor manufacturing, it is used for lithography. Simply put, these lasers etch patterns onto the silicon wafers. Because its wavelength is so short it can create patterns in the wafer chip down to 193 nanometres. Neon enhances the rate of formation, and replacing with helium results in lower rates. These lasers are also used in flat panel annealing for polysilicon-displays and LIDAR. The semiconductor industry is responsible for about 75% of Ne demand.

A little more than half of the global neon supply with the purity necessary for semiconductor fabrication was produced in Ukraine up until the invasion. Two companies, Cryoin and Inagas, are responsible for up to half of the global supply of Neon gas.

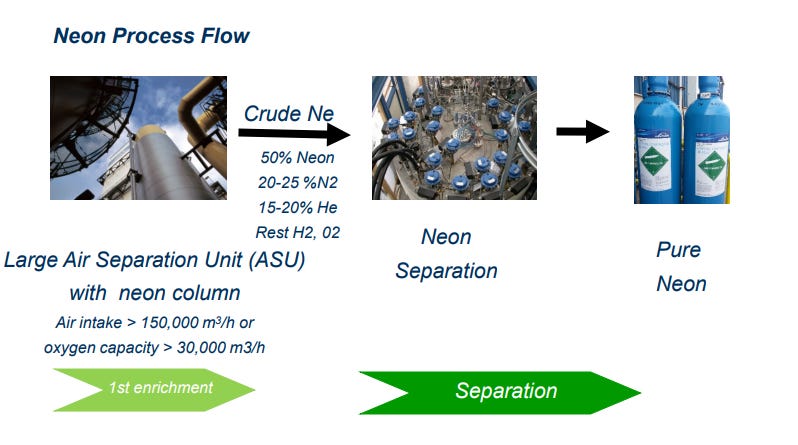

Neon is recovered and extracted via cryogenic Air Separation Units (ASUs) as a byproduct of steel production (or any application where rare gases are used but not consumed). These units separate the components, including rare gases, with columns and membranes. Rare gas purification can be achieved using these same systems. Neon is also recyclable after being used in the process.

The semiconductor industry has experienced supply chain shortages since 2020, Zoltan Pozsar’s most recent letter would like you believe that the endgame is when Ukrainian neon is taken off the market and all chips end up in the hands of military because there’s not enough neon to make them anymore. While prices could rise due to general tightness in the market, it would not impact semiconductor manufacturing costs significantly as the cost of neon is a tiny, tiny fraction of overall costs.

The chips that would be the most significantly affected are NAND memory chips and, to a slightly less significant extent, PMIC, Wi-Fi, RFIC, and MCU some other chips that utilize 248 & 193-nm deep ultraviolet wavelength. Western Digital, Micron and SK Hynix have all come out publicly and stated that they currently have more than 6 months worth of neon, that they can rely more heavily on recycling Neon if they have to and that they have effectively sourced enough to backfill the supply for years into the future. Global demand for memory is expected to decline in 2022 and trough sometime in 2023, so it is unlikely their projections and secured supply will be inadequate.

Not just that, but many of these preparations were taking place well before the invasion of Ukraine. Neon is rare, and therefore expensive, but these constraints were predicted well in advance of the 2022 invasion of Ukraine by China and the United States. Planning for this eventuality begun as early as 2014 with the Russian annexation of Crimea. While short term interest rate analysts may have just begun paying attention to this situation, semiconductor companies have kept abreast of it for years.

Any potential gap between demand and supply has already been filled with reserves, and any potential issues from lower-quality “contaminated” neon have already been resolved. The more expensive neon gets, the more steel producers are incentivized to add capabilities to produce it. There are no geographical restrictions or technological capacity issues. If you produce steel and you have enough money to buy the required equipment and hire the operators (if you haven’t already, which many already have), you can produce Neon. The same equipment can be used to purify it, although this step takes some fine tuning.

Preparation for this eventuality has lead to more capacity for pure neon production in China and the US, which has been ramping up since the invasion. Additional technological advancements including the enhancement of much older techniques that utilize other noble gases (although neon is relatively irreplaceable) have surfaced. Extreme Ultraviolet lithography (EUV) does not use neon at all, and is already used in mass production on more than 15% of chips made by TSMC and Samsung and a higher percentage of the most cutting edge chips (precision missile chips are made using EUV).

The reality is, the supply situation for semiconductors will not get appreciably worse because of Ukrainian neon. The market for neon can become tighter due to Ukrainian supply going off the market, but will not result in any sort of extremes in terms of effects on semiconductor manufacturers.

As mentioned above, every steel producer with an ASU can end up extracting and separating neon. However small, it makes up a component of the air that’s a key feature of the entire planet. That being said, it’s clear to see why neon production isn’t an issue (it’s a byproduct of steel and plenty steel producers in the US and China currently possess the capabilities necessary to recover, extract and separate it), but perhaps the issue is the purity? Well, we can explore that. But first let’s take that realization that it took us ten minutes to come to and apply it to one of Zoltan’s other claims - that Russia wants Ukraine’s neon.

”Donbass is about neon.”

Zoltan Pozsar, Commodity Chokepoints and QT

The true value of Ukraine’s neon industry is in Odesa, where 90% of the neon purification (the part that actually takes a bit more than just having your own country’s steel producers begin using their ASUs to capture and separate neon) in Ukraine takes place. Russia has focused on Donbass, a region that paves the way to a buffer from NATO & a land bridge to Crimea and other warm water ports like Mariupol (some actual motivations for the invasion), but it has pretty much spared Odessa. Not really the actions you’d take if you were invading for the neon, huh?Zoltan makes a comparison to Alsace-Lorraine2 that is actually surprisingly apt, just not for the reasons he thinks. Germany mainly wanted Alsace-Lorraine as a buffer zone because the area contains the Vosges Mountains, which would be much more defensible than the Rhine River if the French ever attempted to invade. It was only much later that they discovered the iron ore. “Donbass is about neon” is a diminutive and uninformed take that’s insulting to Ukraine, Russia, the reader…pretty much everyone involved.

Back to neon purification and contamination. It’s true that you need very high purity neon for chip fabrication, and it’s also true that many of the companies that do so are located in Ukraine. However, as I’ve already mentioned, companies in the US and China have already prepared for this and any potential gap period as the process is perfected to achieve purity won’t affect the chipmakers that truly rely on neon (WDC/SK Hynix/MU, DRAM/NAND manufacturers) immediately because they have reserves and recycling capabilities.

In fact, in what’s perhaps the single most important piece of evidence to the argument that this letter is completely (potentially willingly) uninformed, Western Digital reported this the day before the letter was released in response to a question regarding “contamination” (lower purity neon gas from new suppliers causing difficulty in production):

“Yes, on the flash side, so first of all, as we said, the flash contamination issue is behind us in the fab. We expect bit growth next quarter. We won't be all the way back, but we'll -- we expect to accelerate from where we were this quarter.”

Western Digital are currently investing in a new NAND memory production facility, they are seeing increased demand years out and view it as a positive for volumes. They did not guide for any increase in expenditures due to shortages in the supply chain for 2022. These are not the actions of a company worried about a shortage in a key element of the products they manufacture. Why aren’t they worried? Because Ukraine has been in a state of unrest since 2014.

A neon shortage was predicted in 2015. Steel plants have already ensured they have the ASUs and personnel necessary to produce and purify Neon seven years ago. They predicted back then that it would take 2 years for everything steel producers in China and the US had developed to become fully operational at the highest capacity (fyi, 2022-2016 > 2). Companies that use DUV and produce NAND memory also invested in Neon Recycling Unit adoption, with Cymer, a major manufacturer, reporting that adoption of recycling measures increased 16% in 2016.

Chips produced using neon gas are definitively not the kind that are guiding missiles or doing complex analysis, they’re thicker wafers. They’re the kind that go into things like radios or appliances. Certainly a broad worry for many industries if costs were to go up, and (if the scenario that Zoltan lays out where NOBODY can get chips because “the military” needs all the neon) something that could be devastating if they were unavailable. However, I will state again - the increase to costs for these chips, even if Neon gas were to go up 2-300% in price, would not be that significant. And, again, producers have been preparing for this eventuality for nearly 8 years.

I view this as kind of a cardinal sin of sell side research. It is okay to be wrong in your predictions. It’s okay to miss the mark or be unnecessarily verbose or fail to grasp the implications of a big development. There are, however, a few things that are unacceptable:

Making big claims with zero research to back it up (not just channel checks, I’m talking a straight up 30 minute google search session) beyond what I assume were confirmation-bias inducing fear mongering opinion pieces cherry picked for the most sensationalist, distorted data. Anyone in the steel industry or semiconductor industry, or an equity analyst covering it, would have quickly said “No, you’ve got nothing here Zoltan”. It is not even that complex - a retail investor could have found this out by listening to Western Digital’s earnings calls and doing a few google searches. The only other explanation here is that these things were done but ignored because it didn’t fit the narrative. So, by doing so, this piece:

Propagates sensationalism without a critical analysis or framework of why it might be an overreaction or straight out wrong. Readers are likely already overwhelmed by information about the invasion and how it may affect their decisions in markets. To add another worry they have to research with misinformation is unwarranted and is probably because he:

Goes way too far outside of his lane. Ever wonder why there are so many sell-side firms and specializations for analysts? Macroeconomic, Geopolitical, Fixed Income, Equity Research for every Sector and Subsector, STIR…the list goes on ad nauseum. It’s because this stuff is complicated, requires in-depth knowledge to get right and the customer will be using it to inform decisions that move millions or billions of dollars. It is irresponsible, bordering on egotistical, for the “ Global Head of Short-Term Interest Rate Strategy at Credit Suisse” to begin reporting to customers his analysis on geopolitics, supply chain logistics and sector-specific technological considerations. If he was right, that’s one thing. Maybe if he asked a geopolitical analyst he’d know that the idea that Russia even considered neon as their primary reason to take Donbass rather than warm water ports, a land bridge to Crimea, a buffer against NATO etc. is absurd. Finally:

He is late. They say with investing being early is the same as being wrong. Well, thats more of a buy side thing. If you’re providing research on key specific events that are going to affect the future earnings of potentially hundreds of companies, being early is the same as being right. Being on time is barely acceptable. Being late is unacceptable, not just because it makes your insights unusable but because it shows that you don’t really care. Imagine if you hired a babysitter and you found out that she learned your child was playing with a fork and an electrical outlet, but only did something about it after ten minutes had passed. Or even worse, that they didn’t notice until ten minutes had passed! When disseminating information to clients or the public, being late on a topic is basically saying you either didn’t care enough about the topic until it became expedient for you, or you didn’t notice it when it was relevant but don’t want to let your idea go to waste.

It’s perfectly fine by me to continue writing about this as late as May. Some people don’t follow these things closely, and you can’t go as in depth as you’d like when the event that you’re trading first breaks out. I’d love a deep dive from Credit Suisse, if it wasn’t fearmongering bullshit that was factually incorrect. Please don’t misunderstand me, this isn’t a criticism based on getting projections wrong. That is part of the game. This is a criticism of objectively being wrong and, if he were to call a few analysts in this domain, knowing it.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the first thing every portfolio manager did was run through what Ukraine and Russia’s main exports were, what portion of the global export market they made up, which countries imported them, which supply chains they affected, which companies had exposure to these countries directly or indirectly et cetera. Every good portfolio manager had already done this in the months which the troop movement was front page news and prepared a model covering what would happen in the markets they operate in if Russia invaded.

It didn’t need to be an advanced analysis, “Aerospace/Defense, Wheat, Oil, Energy goes up” was enough to make a killing. But, getting sell side research from a giant (yes, bad, but still giant) institution like Credit Suisse, you might expect a more advanced level of analysis.

I am not bragging here or anything, but this is exactly what I and many others did 3 months ago in February. The first thing I found was the staggering amount of wheat supply that would be taken off the market, so I called people who know their shit when it comes to wheat.

It turned out to be a simple supply/demand equation - long wheat (there were intricacies there too, mainly the type of wheat grown in Ukraine and HRW v SRW, but that ended up not really mattering).

The second thing I found was that Ukraine was a massive producer of neon and that neon was used in semiconductor manufacturing. The next logical step, again, was to talk to people who knew about neon, the steel industry and semiconductor manufacturing. This was on February 26th, and I found out that it presented some challenges to the semiconductor industry, but was essentially a non-issue insofar as the market for neon was concerned. FinTwit picked up on this during the first week of March, concerned for the semiconductor industry, and I offered my input here.

Zoltan has taken the Fin-Twitterverse by storm in the past few months. It’s not hard to see why; his verbose, connect-all-the-dots, “so obvious when you really think about it…if you’re really smart” style of writing and a carefully constructed curation of arguments that seem to deftly borrow supporting theses from one another to weave a grand tapestry explaining why he’s right. Pozsar writes in a way that you’d expect that friend who’s naturally intelligent but let it go to his head would. The prose alternates from highly technical to plain-english, allowing the reader to skim over anything they don’t understand, glean the point from the summary and then pretend they were comprehending it all along. And that’s fine.

Bretton Woods III, his earlier letter, was relatively in depth, made bold claims and, most importantly of all, had that authoritative and in-the-know tone that buy-side loves. That was something most investors sorely needed in the beginning of the year, as inflation seemed to be heading to double digits, “land war in Europe” made a triumphant return after a 75-year sabbatical and the orgy of loose monetary policy that everyone thought would never end came to an end. It even had some decent actionables, as long as you picked the right one. The shipping rate thesis, NOT this widowmaker:

”USD will be much weaker…and the RMB much stronger”

Zoltan Poszar, Bretton Woods III

In fact, I’m sure plenty of people learned a lot from his first article Bretton Woods III (by having to google search definitions, mostly), but I have a suspicion if an everyday sell-side analyst tried to pass off that report to their superior he or she would pretty promptly be told to fuck off.

I don’t want to be overly harsh on Mr. Pozsar, but he should really stick to what he knows. If I wrote a research piece about short term interest rates without so much as a Google search, I assume it would be just as silly as this is. I’m going to choose to believe he was ignorant of all the factors I’ve listed and not deliberately lying, I can’t say for sure why this travesty of geopolitical/tech speculation was published, all I can say is please do not listen to it.

https://plus2.credit-suisse.com/shorturlpdf.html?v=53g1-Vvd1-V

Alsace and Lorraine had spent nearly a millennium under German rule and identifying themselves as German, but had become pretty much fully French by the 1870's and, more importantly, Germany mainly wanted Alsace-Lorraine to act as a buffer zone in the event of any future wars with France. Almost like there was a reason besides the neon…I mean, steel. The area contains the Vosges Mountains, which would be much more defensible than the Rhine River if the French ever attempted to invade. Bismarck was actually reluctant to take Alsace-Lorraine, but German general Helmuth von Moltke, whose nephew of the same name would later serve as a general in WWI, insisted that Germany annex the region for defensive purposes. Also, Germany still recognized that the people living in Alsace-Lorraine had been German for centuries, and there were people who still saw the region as rightfully German and felt a desire to reclaim it. It is worth noting that both Alsace and Lorraine did not want to be annexed, and left France against their will. It was only in the following years it became clear that the real value of Alsace-Lorraine was the minerals buried within them. The iron deposits of Alsace-Lorraine were the second largest discovered deposits in the world in 1918. Also, you cannot make iron ore out of literal thin air.

Fantastic write up. Thanks

Amazing piece Citrini. Learned a lot. Love your style. And I love calling out things, esp. people in positions of influence slipping.

If I may suggest one piece of constructive criticism, there was too much repetition, belabouring the point, at times. Didn't need this many words.