FREE PREVIEW: 26 Trades for 2026

A Thematic Watchlist for the New Year

26 Trades for 2026 is our annual “year-ahead” brain dump for investors who want better preparedness more than perfect prophecy. It’s a curated watchlist of setups where the odds can shift fast, the narrative can re-price faster, and the hard part is simply being early enough to care.

Below are three trades we’re sharing in the free preview. The paid note includes the full list of 26, with deeper writeups, baskets, screens, and commentary.

1. Bullshit Jobs

In his book Bullshit Jobs, David Graeber says:

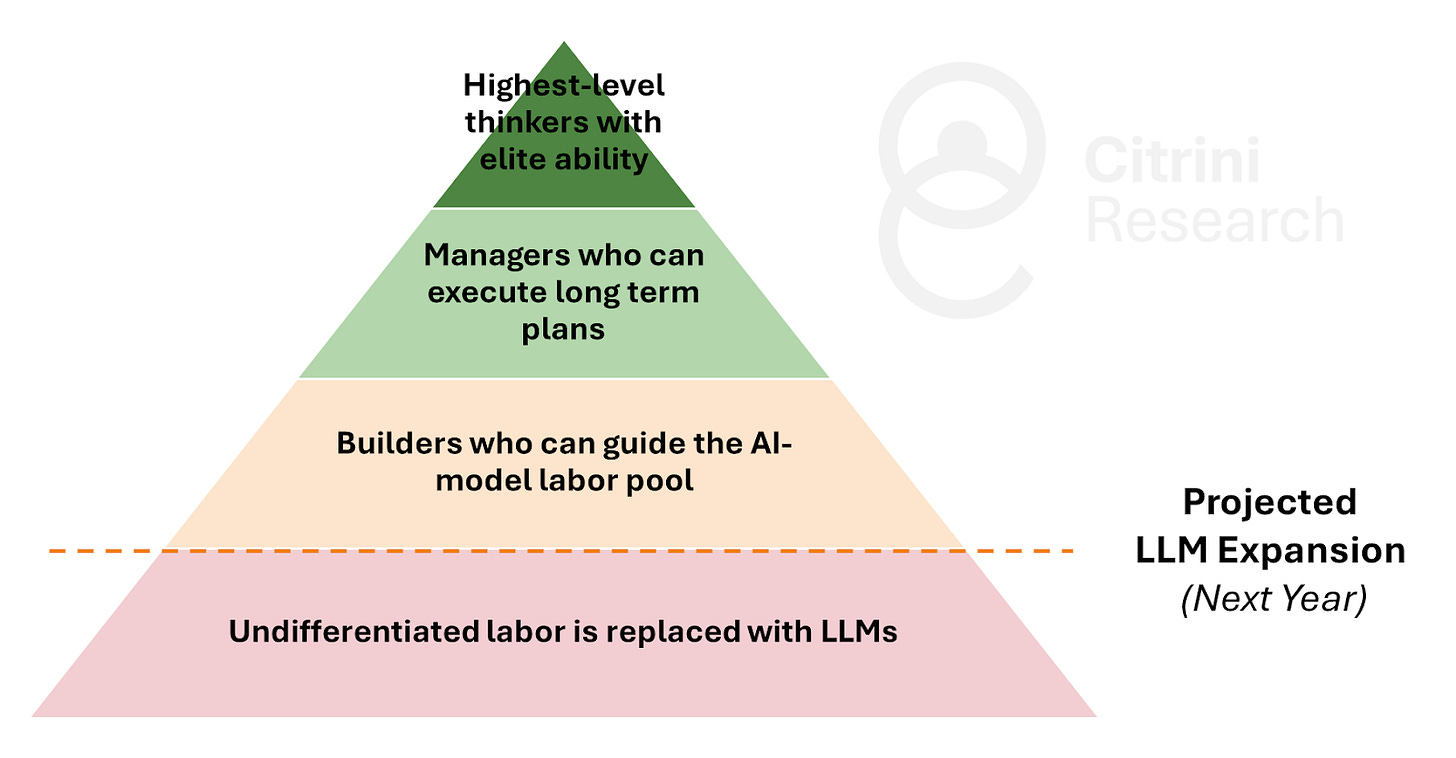

If we think about the pyramid of white-collar labor in an average organization, the vast majority of earnings potential comes from the top tiers. Meanwhile, some degree of “negative expected value employees” will exist in any company at the bottom.

Anyone who has used AI to a reasonable degree for knowledge work knows that eventually many of these “bullshit jobs” will be replaced by AI. But the adoption of technology is always slower than the pace of underlying advancements. We know these advancements are coming fast. We have seen some froth in the “AI Infrastructure” trade, so how could we position ourselves to express our continued belief that AI will keep getting better without taking “the infrastructure bubble pops” risk?

While the market has been primarily focused on what it takes to build and better this technology, it’s going to become increasingly important to think about who actually benefits from its use.

It’s not controversial to say the larger and more paper-pushy the organization, the more likely the median employee can (and will, in the next couple years) be replaced by AI. Large corporations move slowly, but they tend to speed up once they see competitors gaining ground.

We’ve seen a lot of progress in AI, and the concerns that many have raised about broader enterprise adoption are beginning to get knocked down one by one.

Don’t want to give your data to OpenAI? Use Qwen.

Terrified of hallucinations? RAG architectures that force citations from your own internal documents have proliferated in 2025.

Worried AI can’t digest your library of compliance files? Context windows have exploded to millions of tokens, enough for even IBM’s corporate handbook.

Meanwhile, price wars and distilled models have driven down the cost of inference by over 90% since we wrote “25 Trades for 2025”.

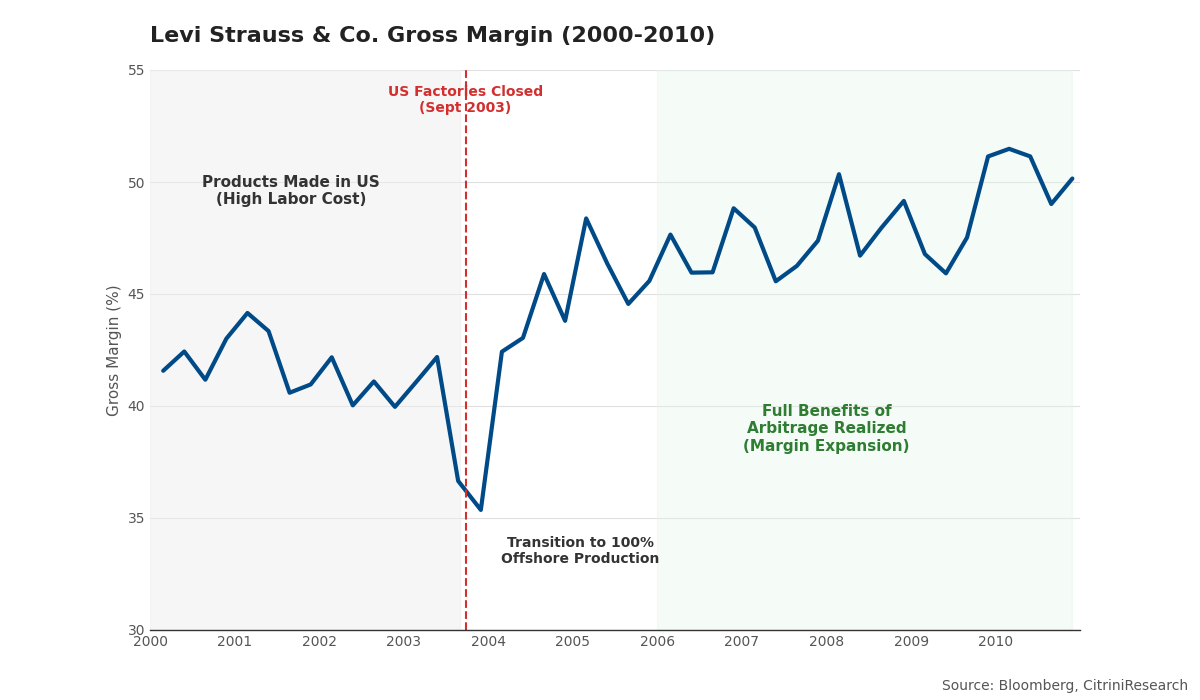

While “AI” is relatively new, we’ve seen the same underlying concept play out over and over. The notion of high-cost employees being replaced by lower-cost resources (both through technology and outsourcing/offshoring) has been driving the US economy forward for decades.

Look at Levi’s gross margins following their effort to offshore production:

Yet even as AI remains the single strongest narrative in the market, most investors have been narrowly focused on the companies building AI and those that will see the most significant and immediate boost to earnings as a result of infrastructure development.

If 2026 is the year we see AI-driven headcount reductions and productivity gains, one might expect that there would be some degree of anticipation of this AI-shift in the share price of companies spending the most on low-value, AI-threatened work. That has definitively not been the case.

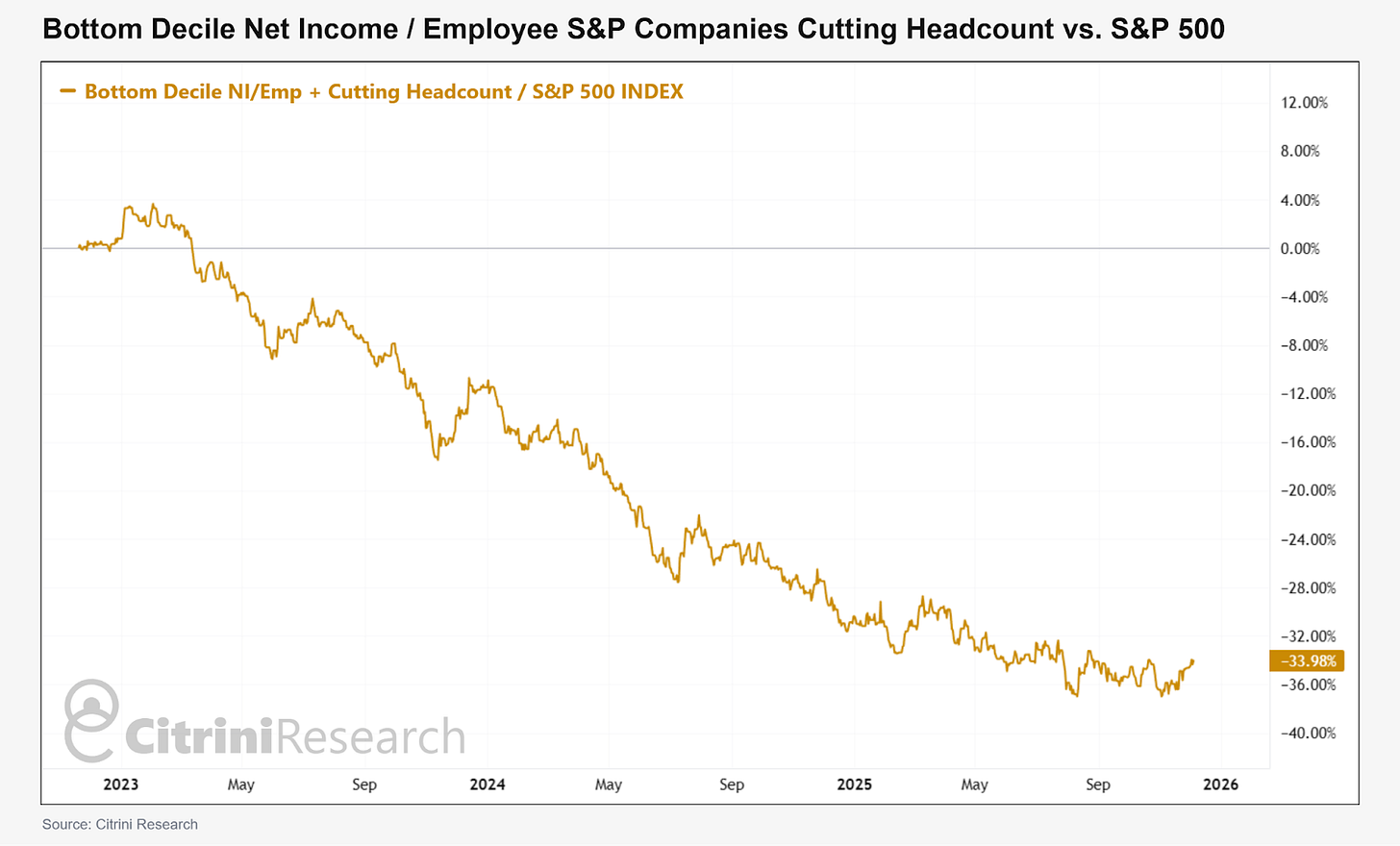

Below, we have created a screen of companies that rank at the bottom of the universe in terms of “net income per employee” that are also cutting headcount, and compare it to the S&P 500.

That’s some pretty massive underperformance!

However, “low decile net income per employee and cutting headcount” is a pretty casual and noisy screen. So how do we create a list of companies that might benefit from the capabilities of LLMs?

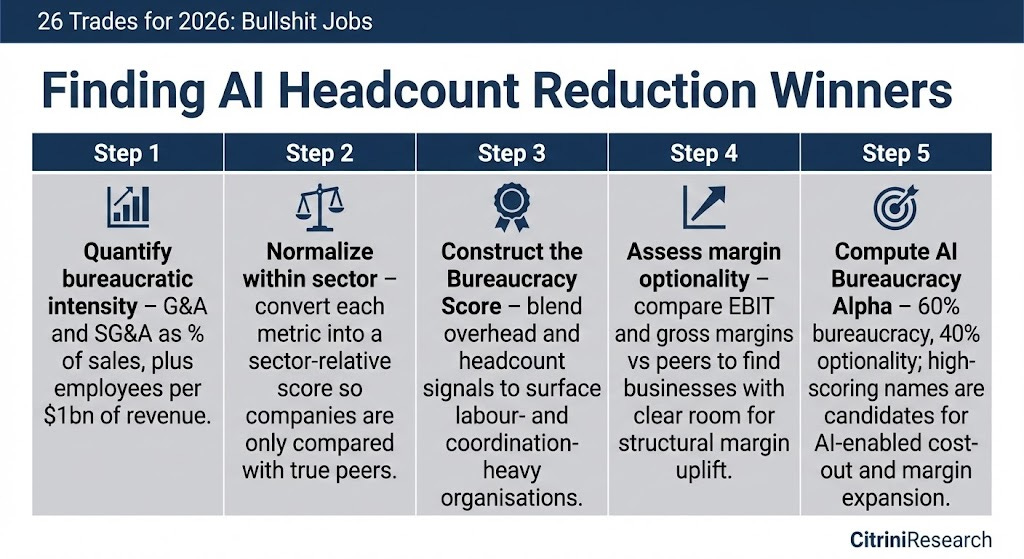

To find large, expensive organizations in high-wage economies that generate less in net income per employee than their peers, we proxy “bureaucracy” using headcount per dollar of net income and overhead ratios (G&A/Revenue, SG&A/Revenue), both converted into sector-relative z-scores. This gives us a Bureaucracy Score that flags firms with unusually heavy administrative and managerial layers versus peers.

Then, we compute a Margin Optionality Score – a z-score ranking of lower margin than industry average – to distinguish which companies should truly be able to earn more if they ran leaner.

Finally, we take a blend of the Bureaucracy Score and Margin Optionality Score to create an AI Bureaucracy Alpha ranking.

We’ve applied these scores to more than 800 names across large- and mid-cap developed markets and taken two sets. First, the top 100 in terms of AI Bureaucracy Alpha ranking and, second, the top 100 scorers out of those who are already reducing headcount.

These are our watchlists as AI adoption by companies picks up. Our screen spans sectors and only looks at companies that could operate in a more lean fashion because they likely entail a significant amount of “bullshit jobs”. However, nobody likes to cut jobs and it’s likely that as long as business goes well many companies won’t realize this efficiency.

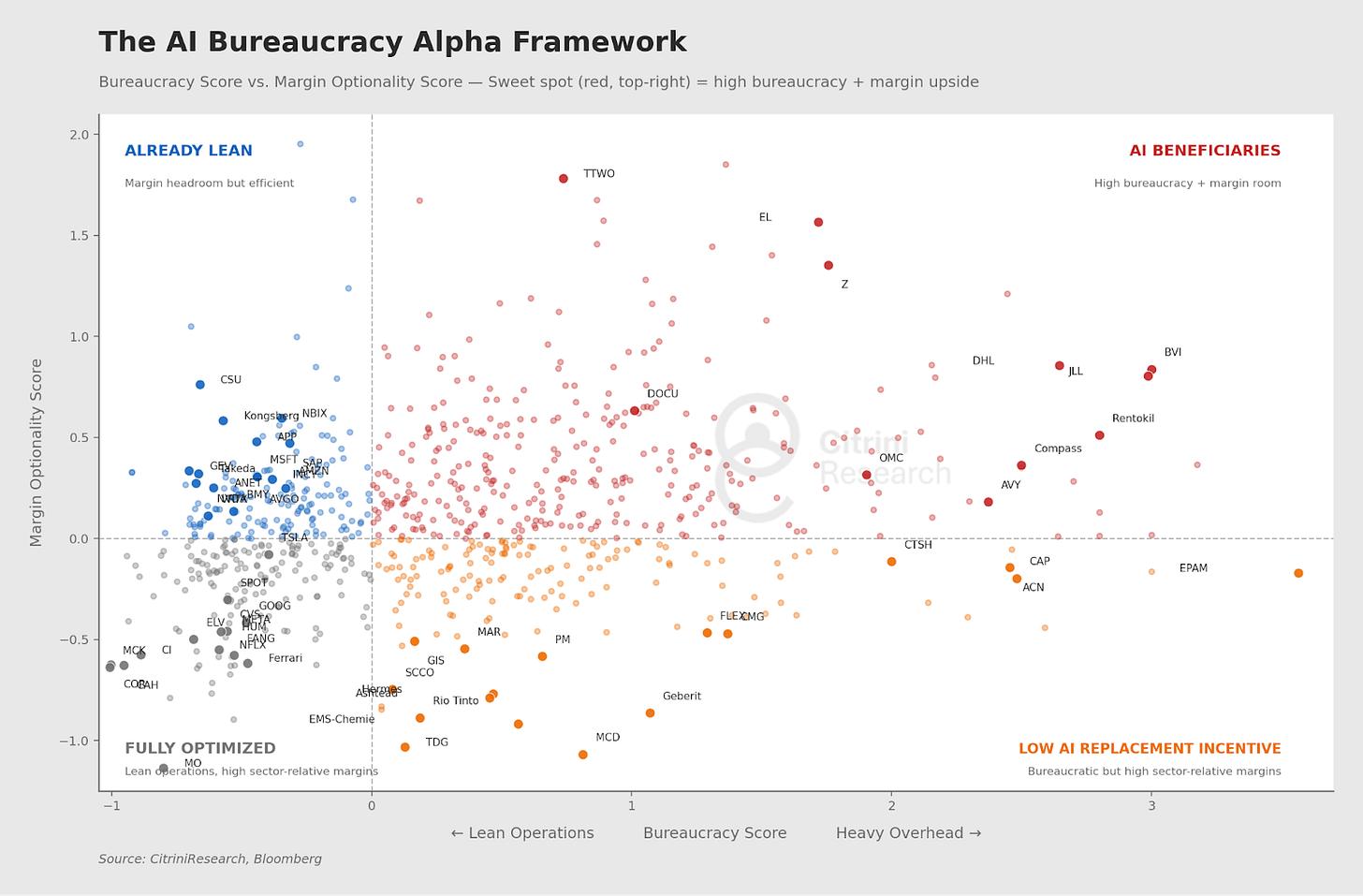

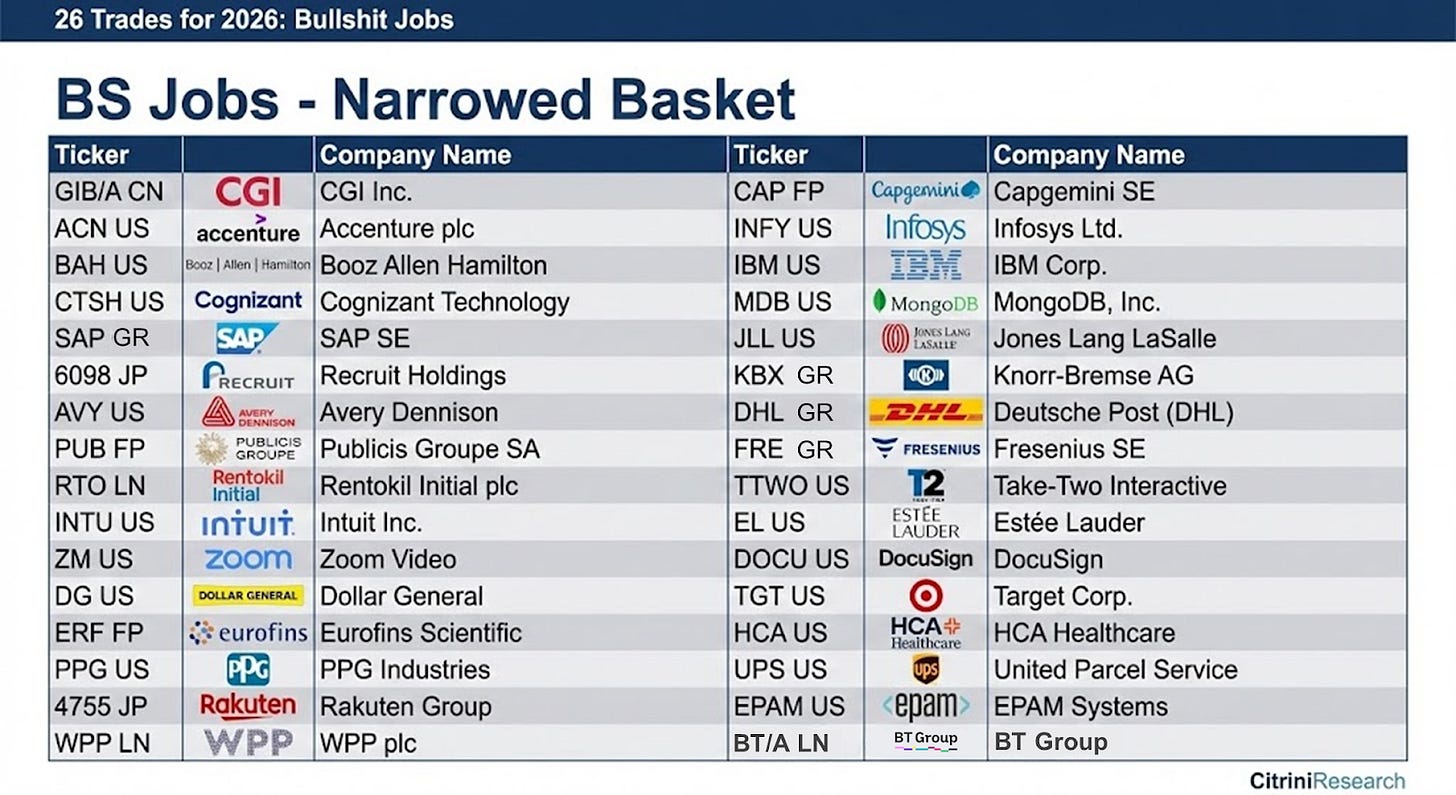

The highest rankings in our list show up in areas that are classic “people factories” – testing/inspection, B2B services, marketing/information and diversified groups with heavy centralized overhead. Many of these names, such as Accenture (ACN US) and Capgemini (CAP FP) have been punished as AI losers.

We think there’s an interesting opportunity here – the companies that are going to not just benefit from cutting their own labor force but also facilitate other large companies doing the same have been put in the doghouse. We did a pretty broad global screen (that we’ve uploaded here) that ends up looking like this:

To further narrow down our watchlist, we’ve checked earnings transcripts and company presentations for mentions of AI/automation driven efficiency gains or job cuts. After all, you can’t seize an opportunity if you’re not looking at it.

For example, Accenture recently laid off about 11,000 employees over three months. CEO Julie Sweet said the firm is “reshaping its workforce for the AI era,” adding that workers whose skills can’t be retrained for AI are being let go; she explained that upskilling will be the focus and advanced AI is becoming part of everything Accenture does.

BT Group (BT/A LN) was already planning on cutting 40,000 jobs – CEO Allison Kirkby told the Financial Times in June that they’d go even further due to AI efficiencies.

We notice a lot of names that have high margins relative to their sector and rank low on bureaucracy score (e.g. “already optimized” companies) are already talking extensively about AI-driven efficiency gains on their earnings call – a good example is CH Robinson (CHRW US).

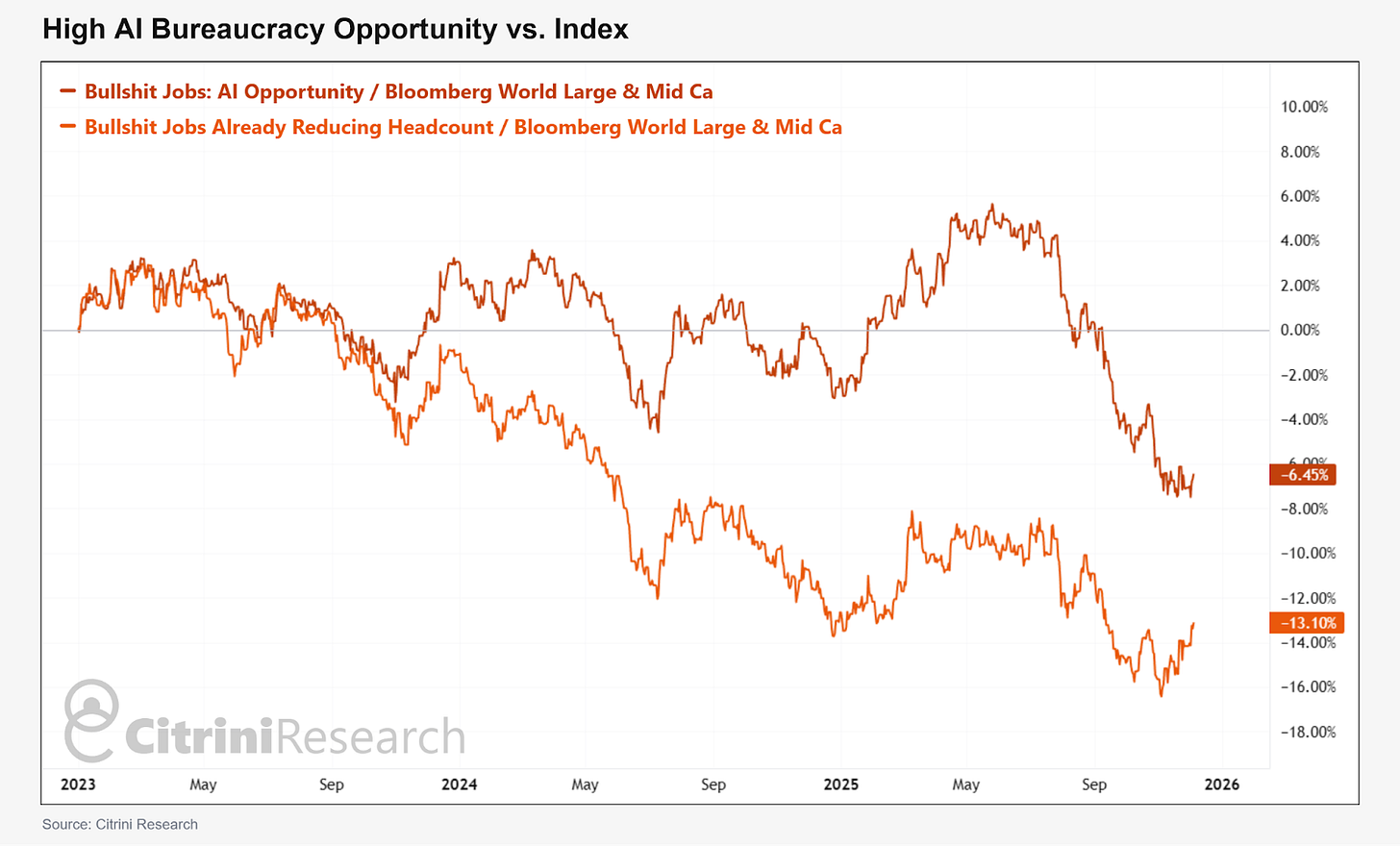

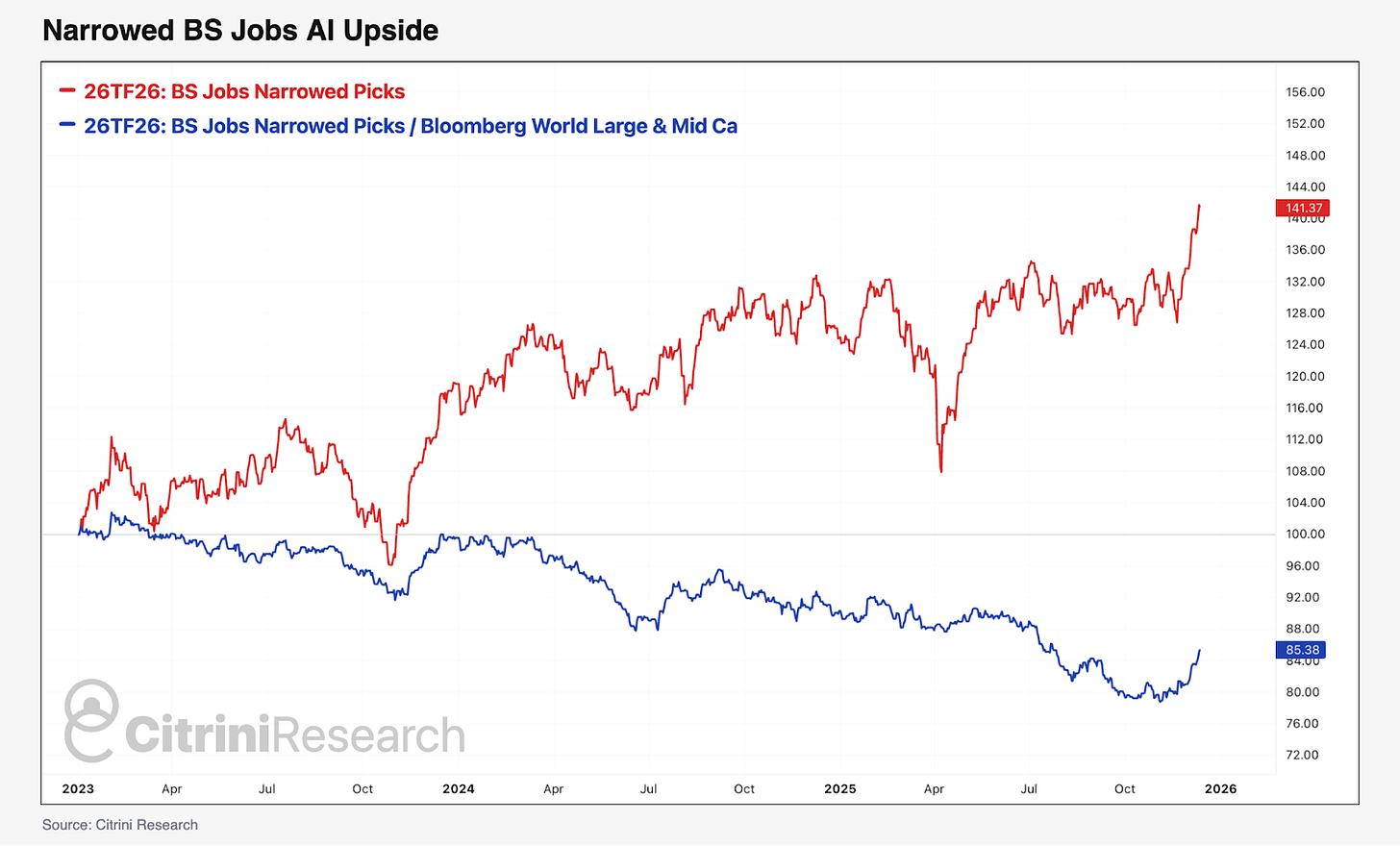

Our narrowed basket shows serious underperformance since ChatGPT came out, but recently these names have risen sharply and outperformed. This could be a coincidence, or it could be the result of the market finally recognizing that AI will benefit more than just the model makers.

A note: the above group previously included Confluent (CFLT US) but, in between writing and publishing, IBM decided to acquire it. That’s probably a good sign for the rest of the thesis. Another note: While Zoom does fit all of our criteria, we’d consider maybe not including it…a lot of BS jobs entail a lot of Zoom use. Additionally, while I’ve excluded Utilities and Financials to standardize our screen, the Insurance Brokers (e.g. BRO, AJG etc.) are pretty interesting qualitatively as having upside to paper-pushing reduction.

2. Inference on Device

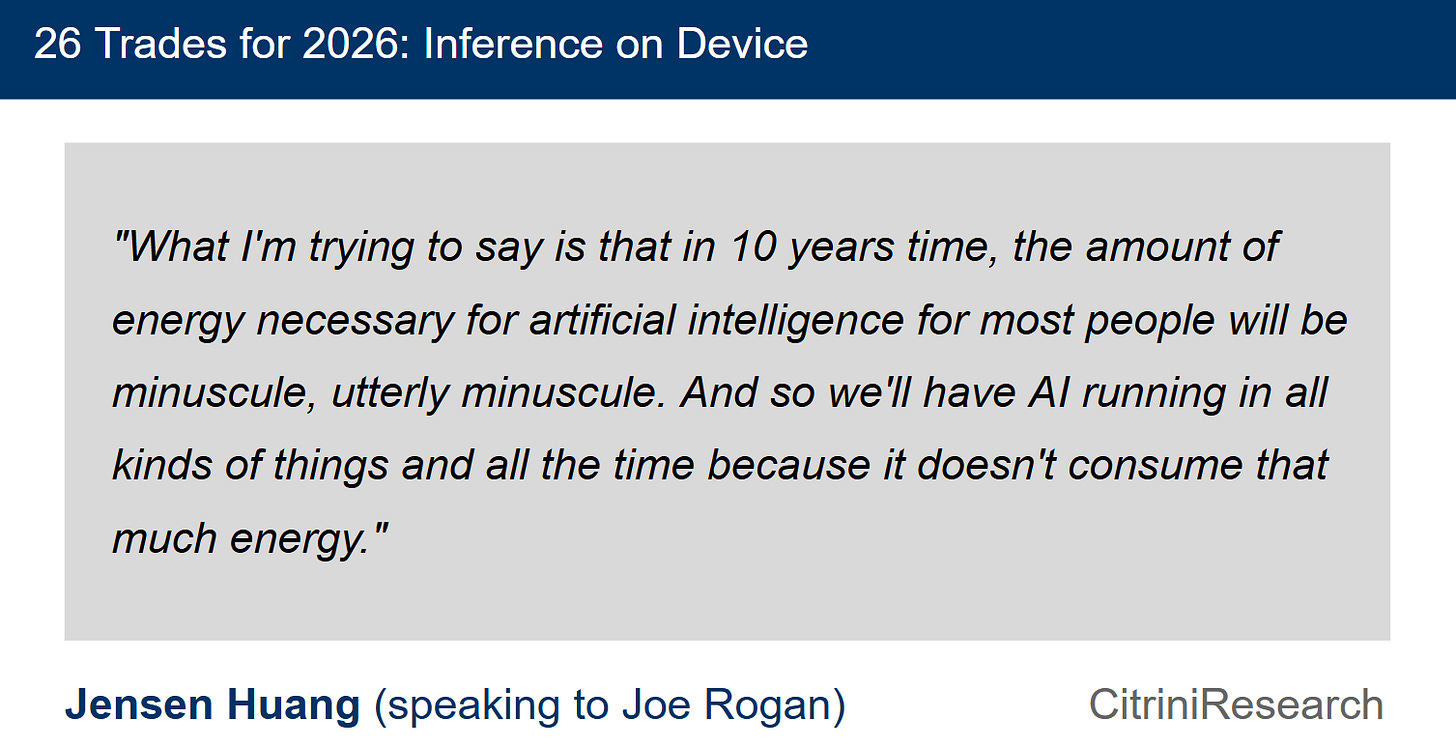

When people say “edge AI” or “inference on device,” they’re describing a simple idea with complicated implications: running AI models locally on your phone, laptop, or other device rather than sending your query to a datacenter somewhere and waiting for the answer to come back.

Right now, when you ask ChatGPT or Claude a question, your words travel to a server farm, get processed by a model running on very expensive GPUs (or TPUs!), and the response travels back to you. The whole round trip takes a second or two, which feels pretty fast. It’s actually an eternity in computer time. Edge AI flips this. The model lives on your device. Your query never leaves your phone. The response is generated locally. No internet required.

This sounds obviously better, right? Faster, less expensive, works offline…so, why isn’t everything running on-device already? Because there’s a catch. Actually, there are several catches (which we outline below).

This edge capability is necessary to usher in the rapidly approaching age of Agentic AI. For example, this video shows Doubao’s new OS-level agentic AI integration comparing prices of a coffee and ordering on the cheapest app – a very early form of what agentic on-device AI looks like. This agent is not interacting with apps via APIs but via the user interface (i.e. reading and clicking the screen for you, aka a “GUI Agent”). Pretty cool, but also an example of the limitations present (it takes three minutes and doesn’t technically succeed in picking the cheapest option).

Whether you’re bullish or bearish on edge AI as a theme depends largely on how you weigh those catches (and others we’ll describe) against the benefits. I’ve seen a renewed interest in edge AI online, but I’ve only seen it discussed in very binary terms. I think, for 2026, it’s time to have an honest and frank discussion as to the bull and bear debate for on-device AI.

The Bull Case

The 3 pillars of the Inference on Device bull case are:

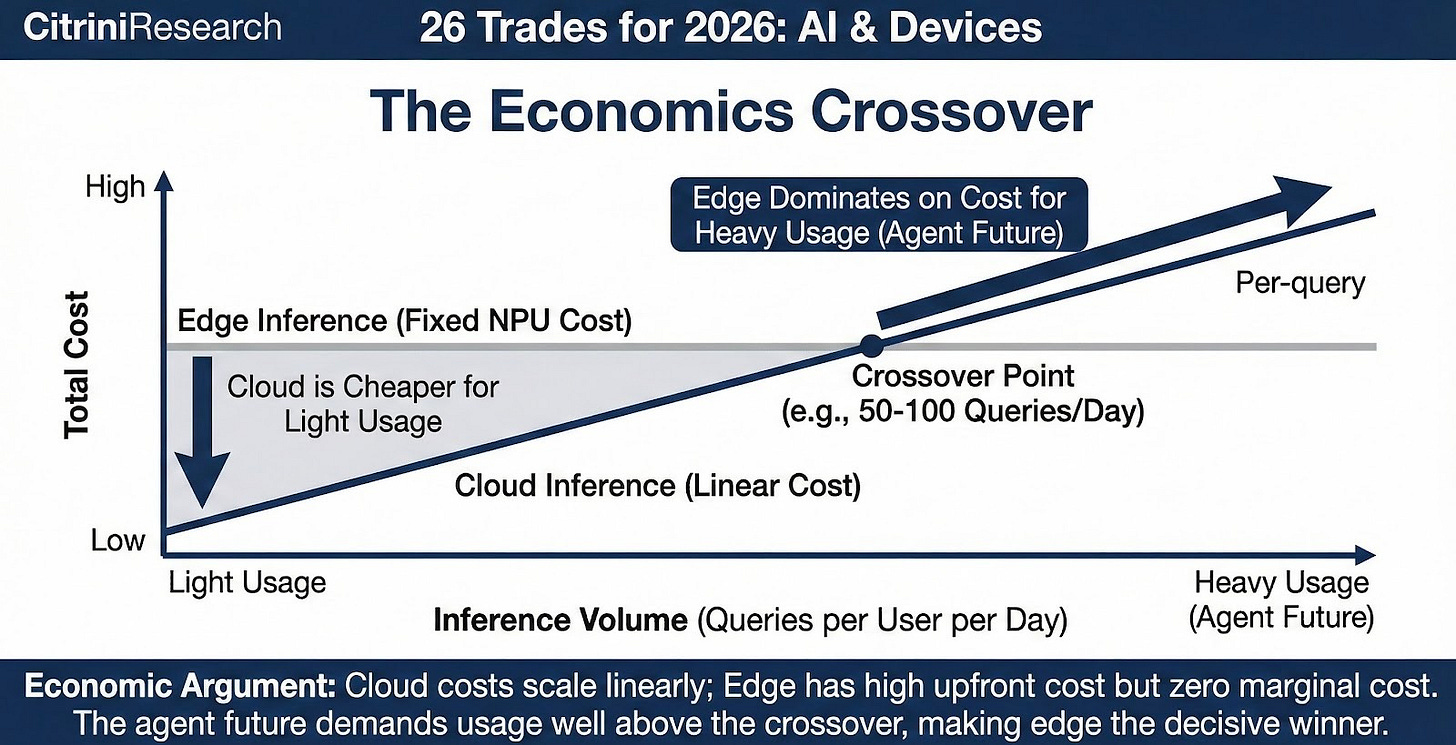

1. Inference Economics for “Always-On” Agents Favor the Edge

Cloud inference is a marginal cost game. You pay per token or per compute-second. While individual inference costs are dropping (optimization, better hardware), the cost curve remains linear relative to volume.

Right now, running inference in the cloud is “cheap” because most people don’t use AI assistants that heavily. Now imagine a world where your phone’s AI agent is active all day, processing context, monitoring your screen, anticipating your needs. If an agent is constantly running in the background (processing audio, watching screen context, predicting next actions) that volume explodes, making the OpEx prohibitive for a consumer service.

At edge prices, it’s just battery life and silicon you’ve already paid for.

The bull-case is that, while cloud inference model works for occasional, high-complexity queries. It doesn’t scale to ambient, always-on AI assistance that extends beyond the realm of chatbots. It makes no sense to send every pixel and every keystroke to the cloud. That is a physics problem. We need AI at the edge to handle the sensory data.

2. Latency Requirements make Cloud Impractical for Everyday Use

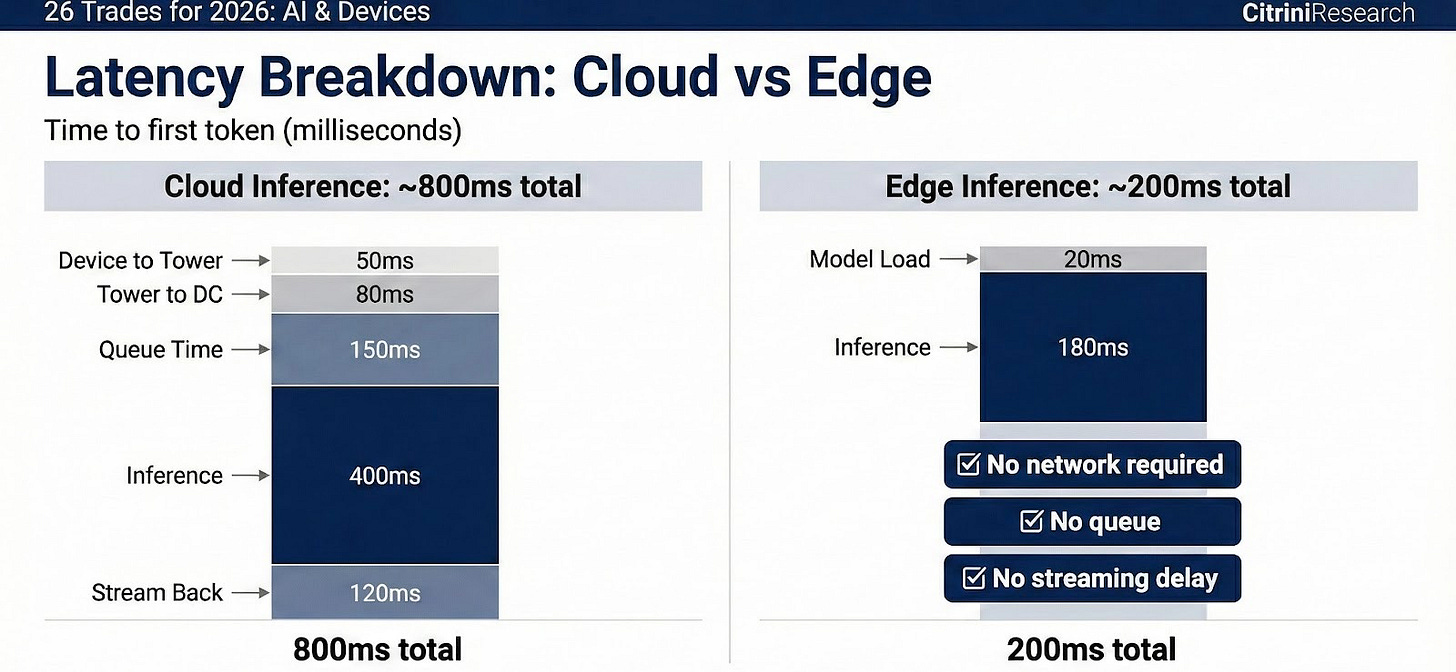

When you’re having a conversation with an AI assistant, anything over about 200 milliseconds starts to feel laggy. Your brain expects conversational pacing. A cloud round-trip, even on a good connection, adds 100-300ms before the model even starts generating. Then you have token-by-token streaming back to the device.

For simple queries, this is fine. For agents that need to take actions, read your screen, respond to context in real-time, it’s not. We’re all happy right now with Nano Banana Pro saving the investment banking analysts time by aligning their logos well enough to avoid the ire of their MD and we’re happy to wait in order to get a really good answer on a prompt, but chatbots aren’t the AI future. Not all of it, anyway.

Autonomous agents, sensory data processing, world models, digital assistants that can read your screen, order you an Uber, do real-time voice translation, book you a reservation, get you a refund for a missed flight…generally do most mundane things you don’t want to do. These use cases require near-instantaneous latency or they just don’t work. A simple case: I’d love to be able to tell my phone “get me an uber back to my hotel” and have it just do it – but not if it takes 3x as long as me doing it myself.

The bull case for inference-on-device is that the consumer-facing agentic vision that we desire requires responsiveness that cloud inference simply cannot deliver.

3. Hardware is Improving

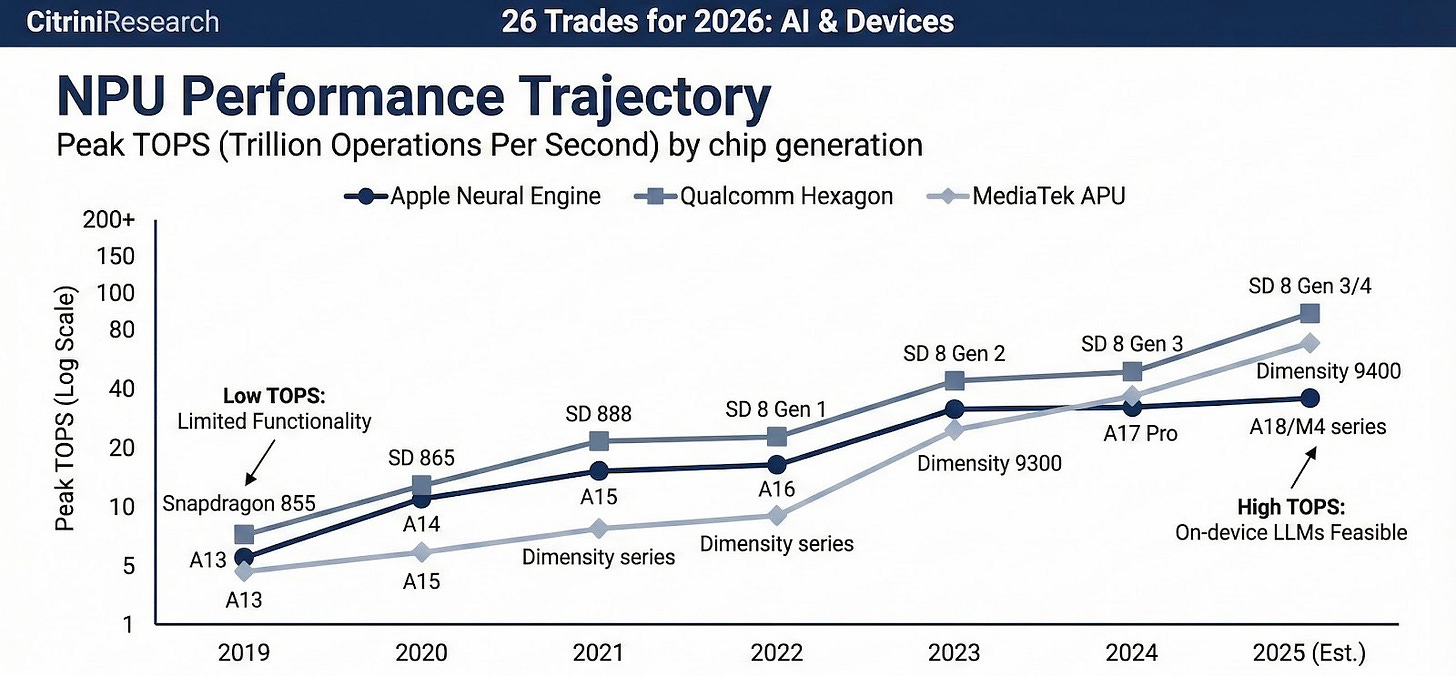

The bull case is that on-device capability is improving faster than people realize, and that the gap between “what runs locally” and “what requires the cloud” is narrowing. Apple’s Neural Engine has improved roughly 2x per generation. Qualcomm’s Neural Processing Unit (NPU) trajectory is similar. MediaTek just announced a Dimensity 9500 with a 56% power efficiency improvement in the NPU.

The Bear Case

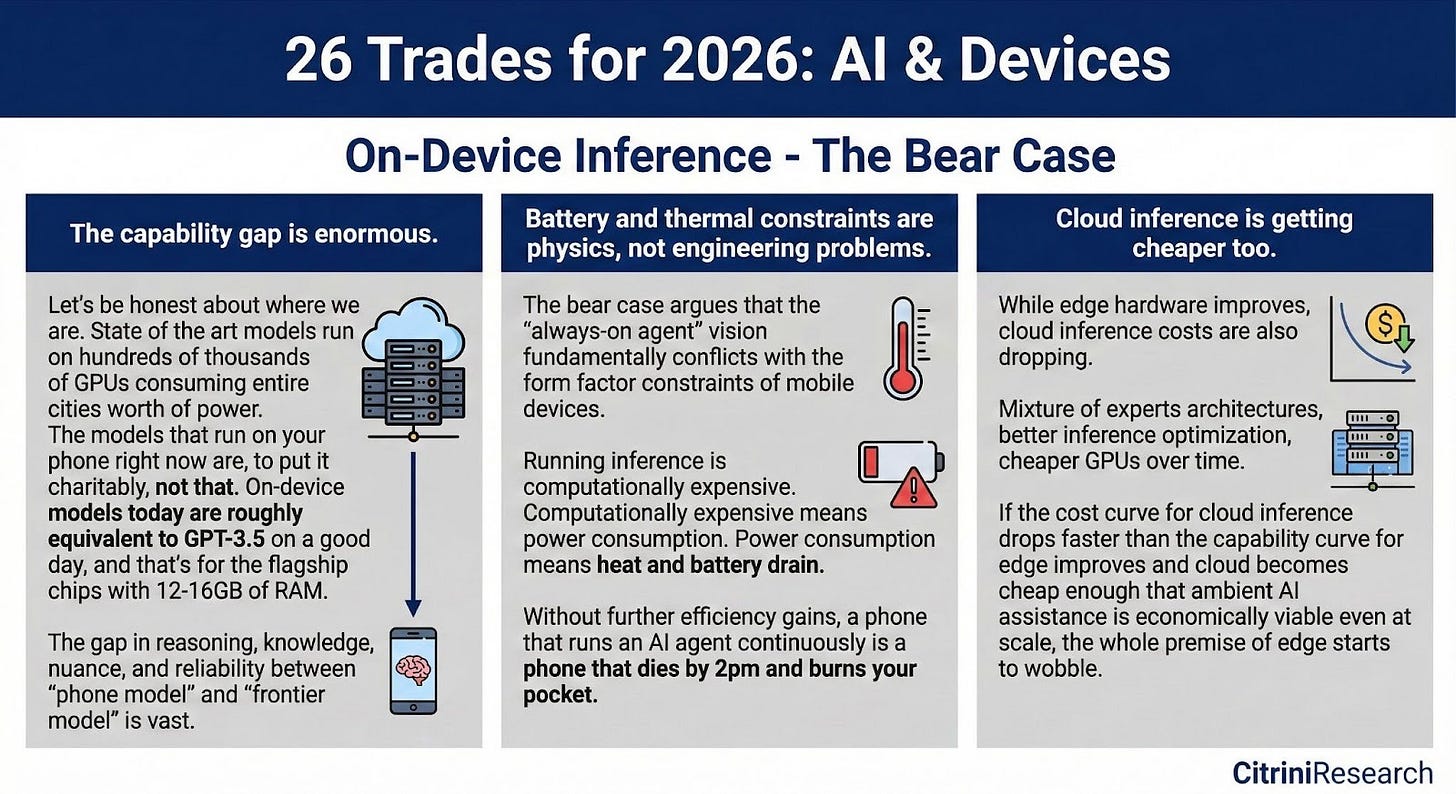

The bear case for on-device AI essentially boils down to “why would you want a worse model running on your phone when you can have a better one in the cloud?”.

Cloud performance is hugely superior, you avoid battery life constraints, and we expect that cloud inference costs will continue to plummet.

These are all good points but – but they’re all potentially solvable problems. Therefore, we should take the possibility of an on-device-lead investment cycle seriously. The most significant risk to doing so, however, has less to do with the merits vs. drawbacks of on-device AI and more to do with the hardware inputs.

The Most Compelling Bear Case: There’s not enough RAM

The hard constraint is not compute, it’s memory.

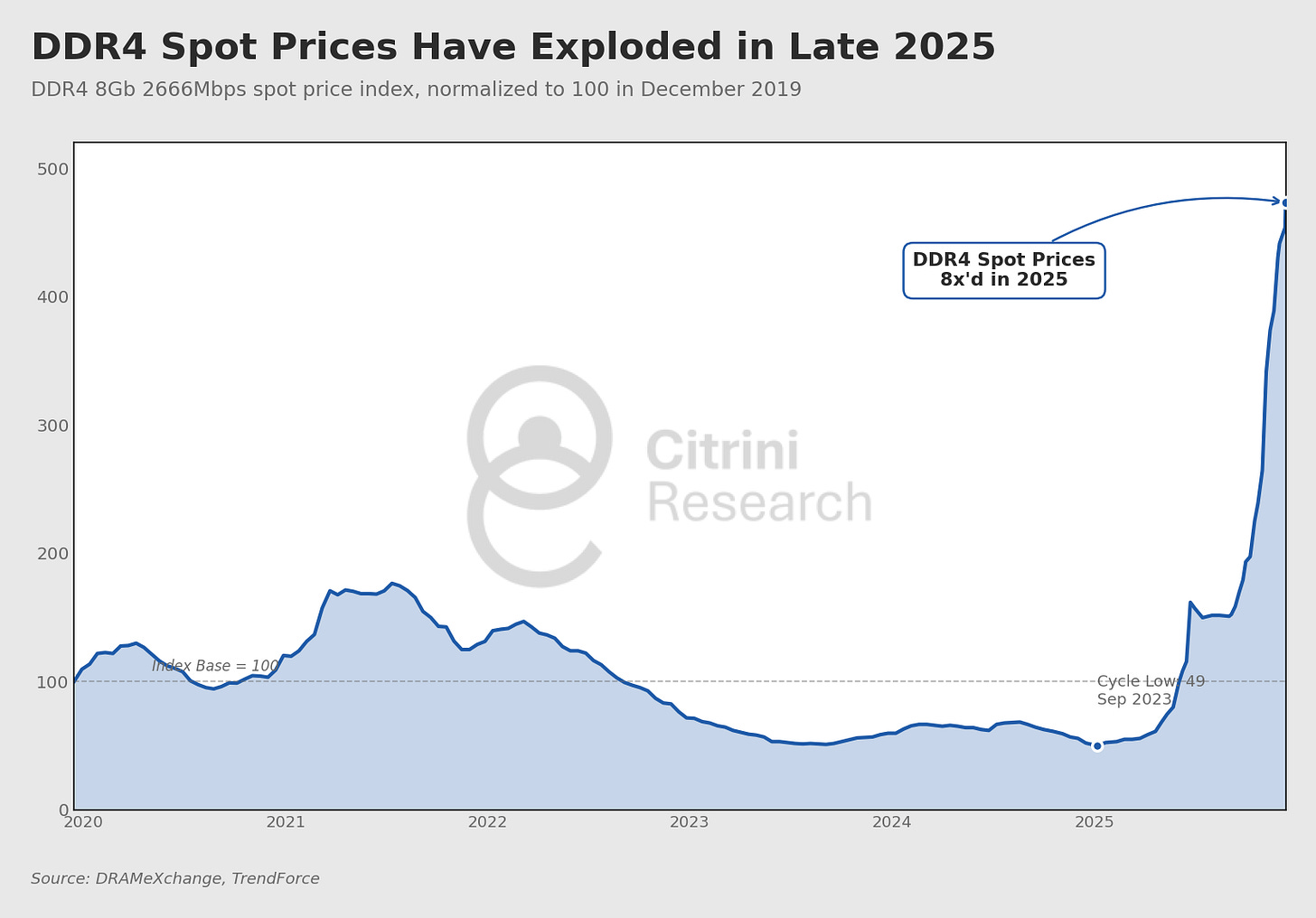

Dell COO Jeff Clarke summed it up nicely when he said “I’ve never seen memory-chip costs rise this fast.”

I know it’s cool to be the cyclical cynic, whenever a cycle inflects you go “well, we know how this one ends!”. And that’s great, I’m sure you’re very smart. But Jeff Clarke is 62 years old and has been navigating semiconductor cycles since the Reagan administration. When he says he’s never seen anything like this, I’m inclined to believe something a bit crazier than a normal cycle is going down.

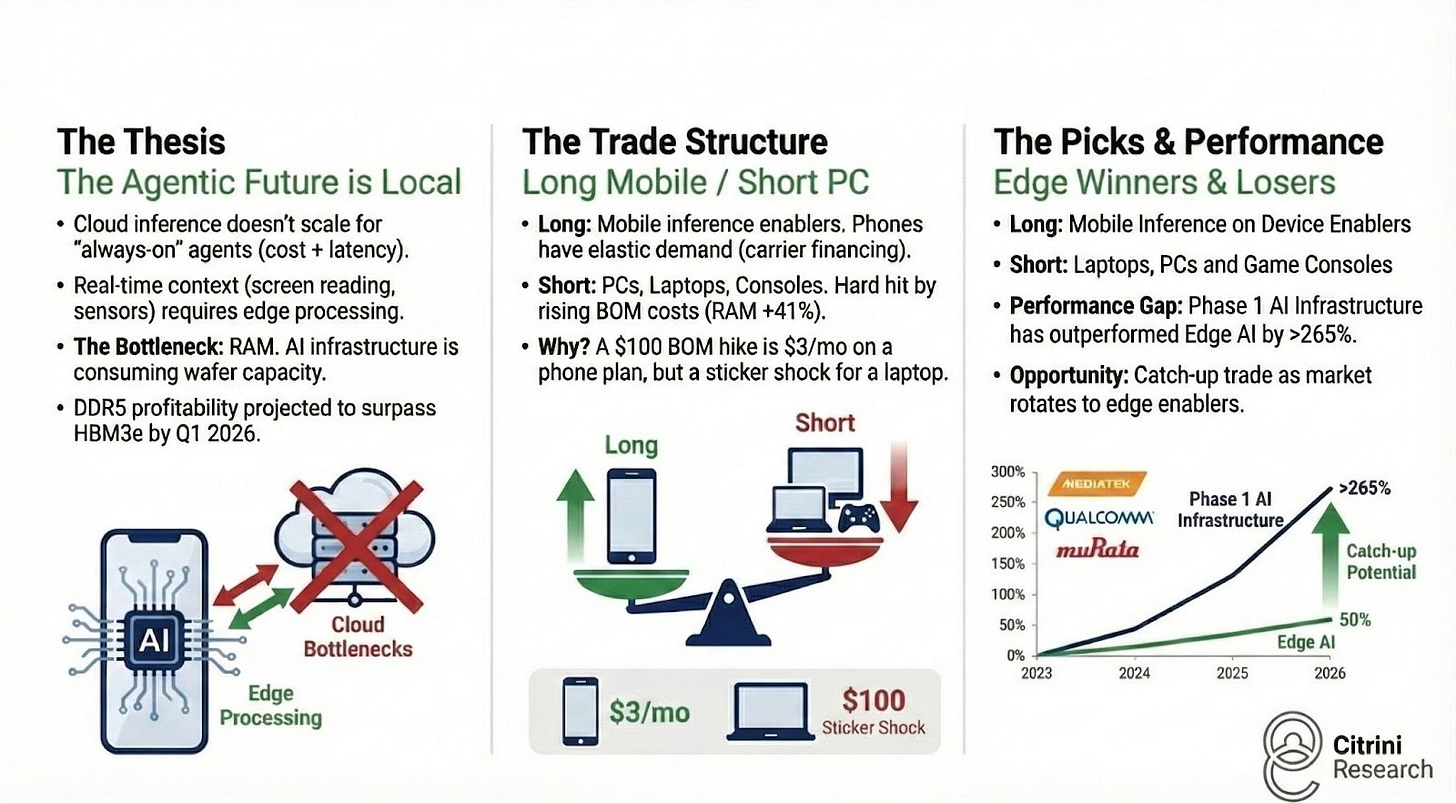

AI infrastructure is consuming wafer capacity. Cloud service providers (CSPs) are upgrading to high-performance platforms at a pace that’s driving memory content per server meaningfully higher. DDR5 profitability is projected to surpass HBM3e by Q1 2026.

Selling the stuff that goes in your laptop – memory – is about to be more profitable than the AI poster child we’ve spent the last three years kvelling about. When that crossover happens, memory suppliers may actually allocate away from HBM toward server DDR5 to capture the spread. We’re looking at a supply chain realignment that could take years, not quarters, to normalize.

The good news is that at least this makes for some good memes.

Kidding…The good news, however, is that RAM is a bottleneck. If the AI trade thus far has taught you anything, let it be that investing in the technology bottleneck is extremely profitable.

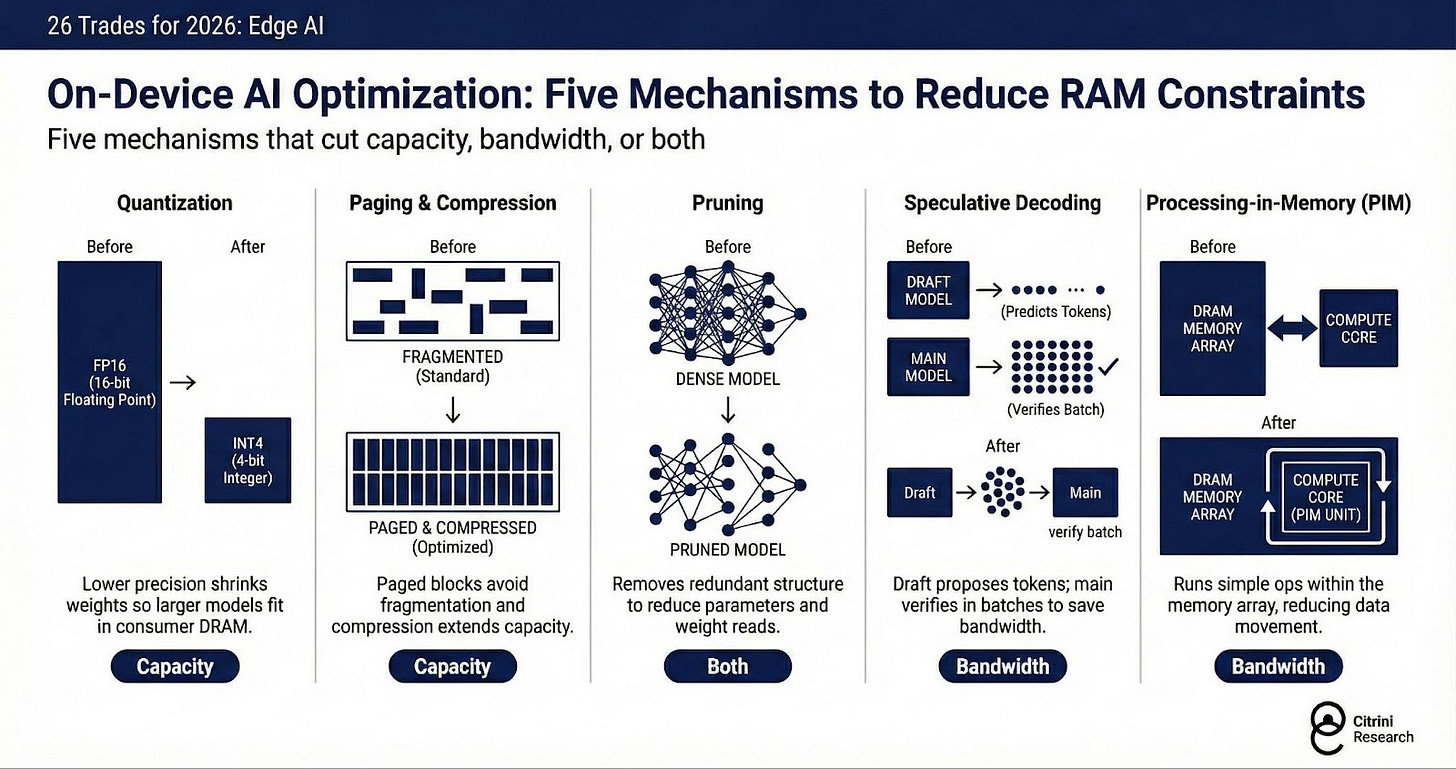

And while I don’t know the precise timeline, I do know that the primary beneficiaries will be those that deal with on-device AI. There are already multiple ideas being worked on to solve squeezing more useful intelligence out of the same RAM.

Still, while that sets up a great vector for increasing investment into NPUs and on-device inference, the bad news is that memory is expensive, likely to stay that way for at least the immediate future (more on how to play the inevitable correction later) and the harsh reality is that memory is essential for agentic AI regardless of whether it’s in the cloud or on your device.

Nevertheless, we can structure a trade that cancels out the lack of available memory, allowing us to capture any upside in the on-device enablers while waiting for memory supply chains to re-adjust or breakthroughs in memory efficiency.

We simply short consumer electronics that are even harder hit by memory price and that have less potential for a renewed surge of demand and refresh cycle due to on-device AI models.

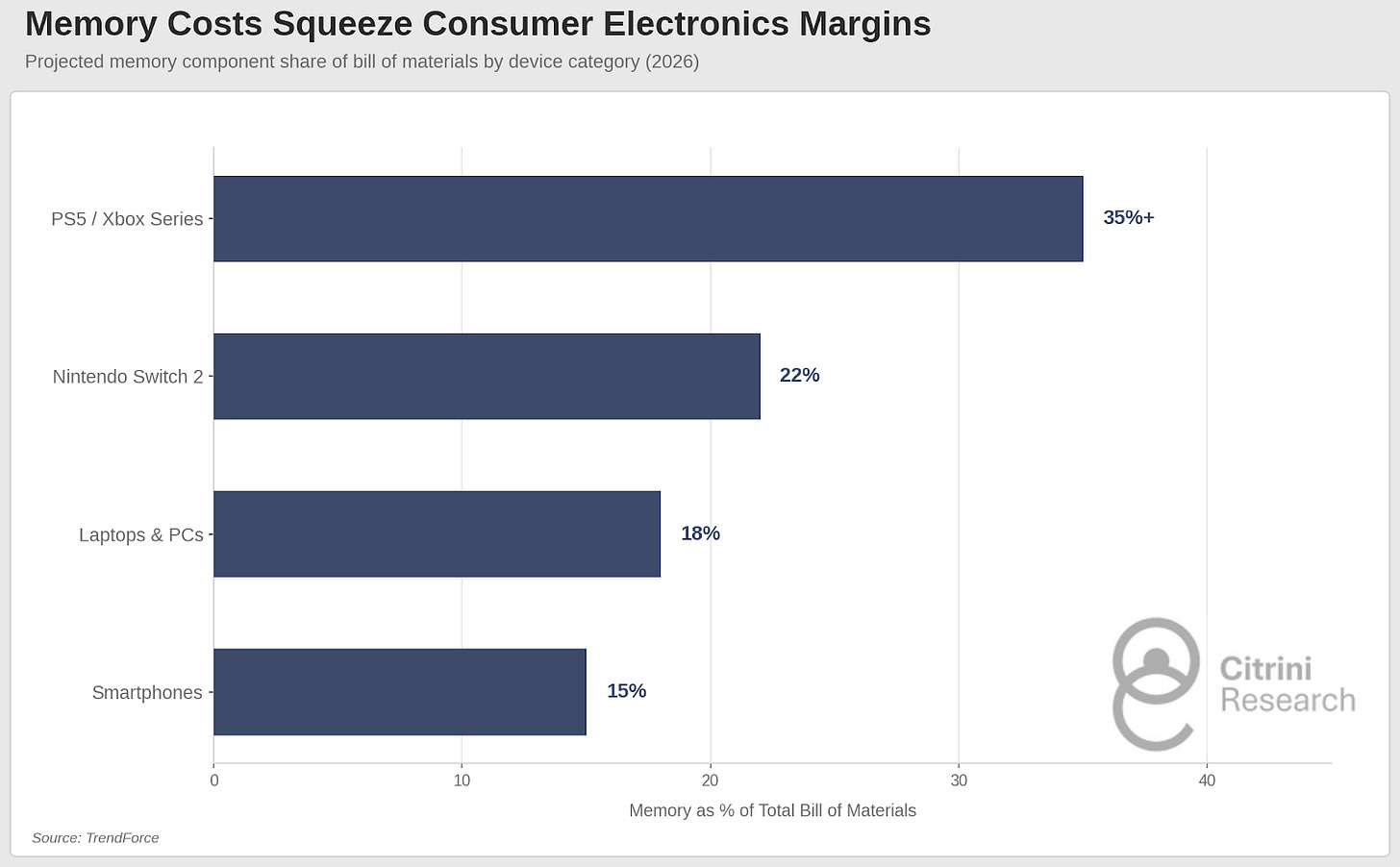

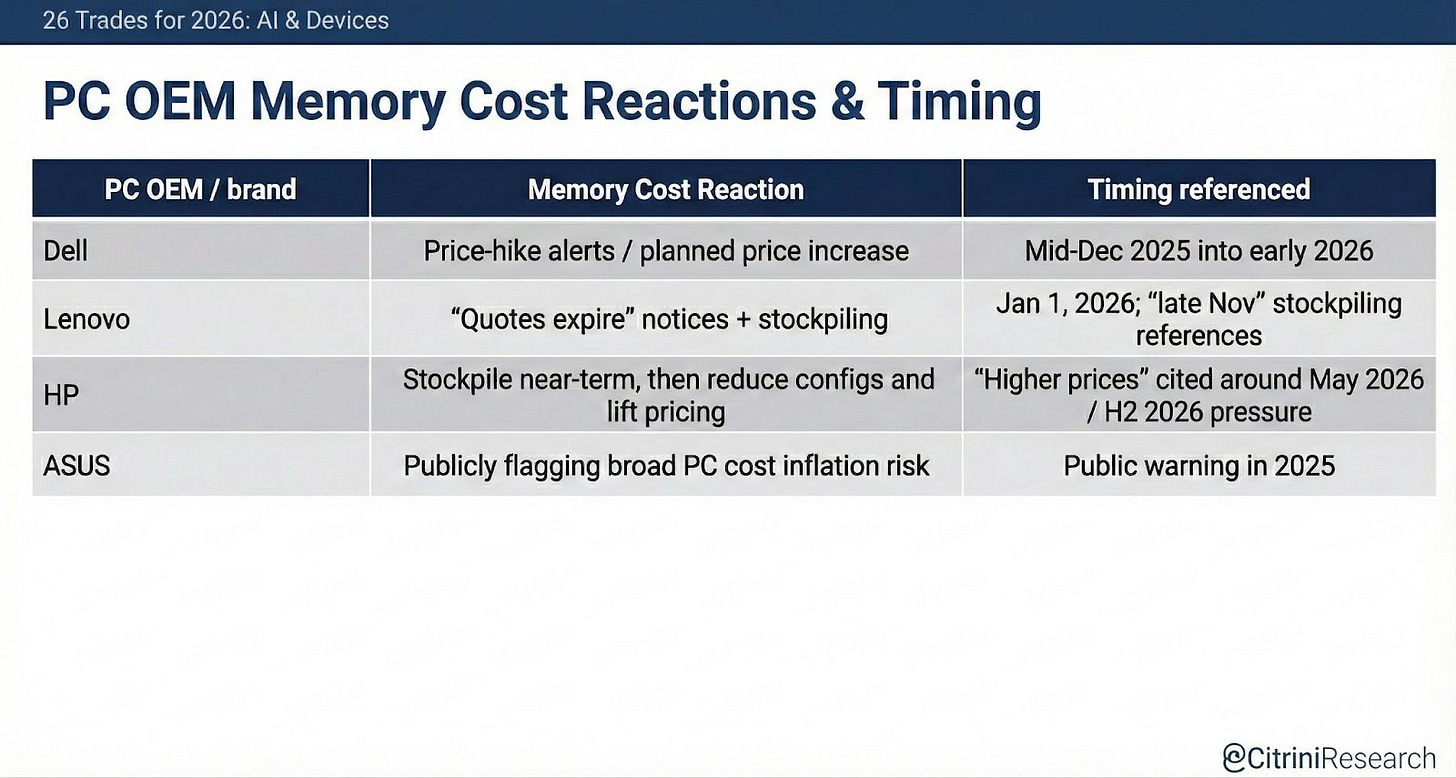

Nintendo’s Switch 2 launched at $450, a full $150 premium to its predecessor. The 12GB RAM module alone costs 41% more this quarter than last. Things are equally as bad in PC and laptop world:

Here’s why I like this pairing so much – while I’m cautiously on the bull side of the “inference on device” argument, I’m very confident that the device is your phone – not your laptop, PC or PlayStation.

The phone is winning the agent era because the phone is where the agent belongs.

When AI agents can order food, book rides, and draft emails across applications without you opening any of them, the phone transforms into a general-purpose assistant.

Will your laptop be able to do this? Technically, yes. Will it? No, because the laptop isn’t with you on the train, at dinner, walking down the street. It doesn’t have the camera, microphone, and sensors that provide rich environmental context. Microsoft has been pushing “AI PCs” for over a year now. Copilot+ PCs are not selling. The upgrade cycle isn’t materializing. Meanwhile, 75% of Samsung Galaxy users reportedly interact with AI features daily.

Phones have more elastic demand compared to other devices.

Finally, compared to laptops and PCs, smartphones benefit from a distribution model with inherent elasticity that no other consumer device category enjoys – carrier financing. When memory costs rise and push phone BOM up by $100, that increase gets amortized across 24-36 monthly payments. A $1,000 phone becomes $27.78/month. A $1,100 phone becomes $30.56/month. Compare that to the PC buyer standing in Best Buy, staring at a Dell XPS that now costs $1,800 instead of $1,500.

The market always has to make things binary, but just like how the debate over “Cloud vs On-Prem” ended up with “Hybrid Cloud”, the rational end state is hybrid here as well. We’re not asking models on-device to cure cancer or design a chip. We’re asking it to answer emails, schedule meetings, call us a car and make us a dinner reservation. Inference on your device can happen without destroying cloud. But, in my view at least, it does have to happen.

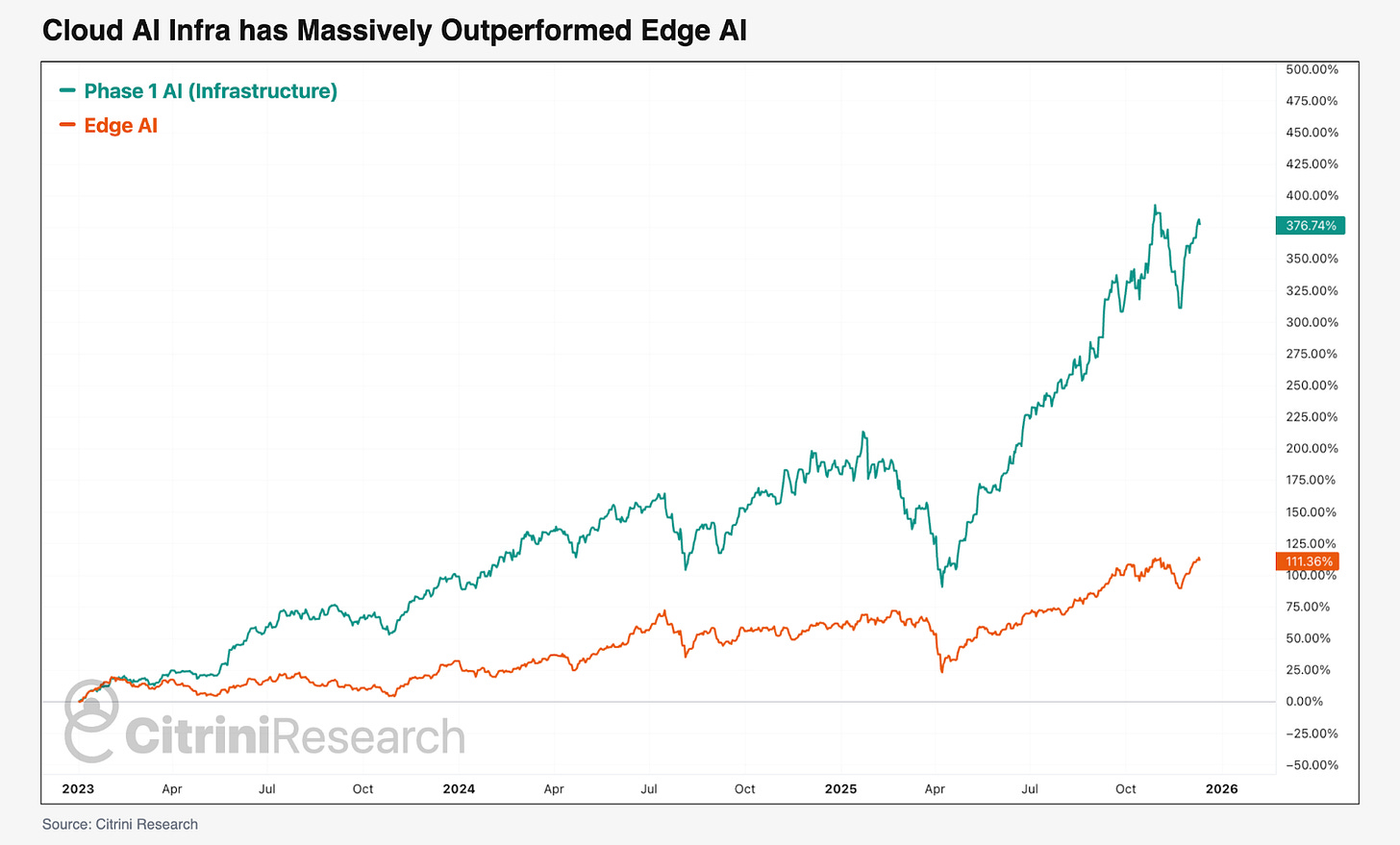

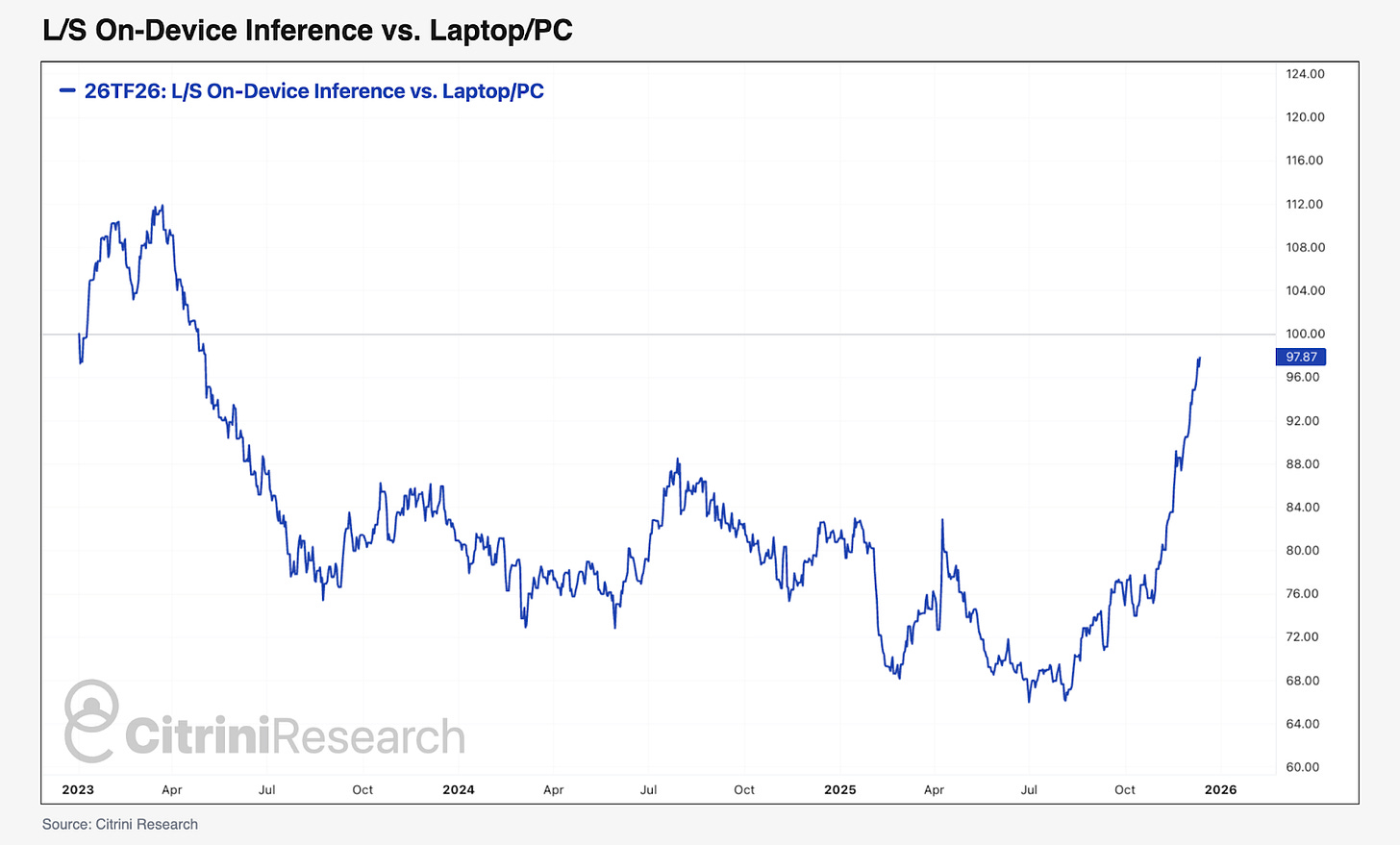

In the market, the mobile overhang and data center primacy has resulted in a massive rally for everything “AI data center” and a relatively paltry rally for everything else. Our broad (125 names) basket of AI Data Center Infrastructure Beneficiaries we titled “Phase 1” in May 2023 has outperformed our ~25 name basket of Inference on Device Beneficiaries we made in July 2024 by more than 265% since ChatGPT’s debut.

Mediatek (2454 TT) has doubled but Broadcom (AVGO US) has octupled. Mediatek trades at less than 20x forward EPS, while Broadcom’s is above 80x on optimistic forecasts. This makes me very interested in potentially gaining exposure to what seems inevitable (though currently difficult) at a discount, and if I can do so while neutralizing the most significant risk delaying progress (memory prices)...

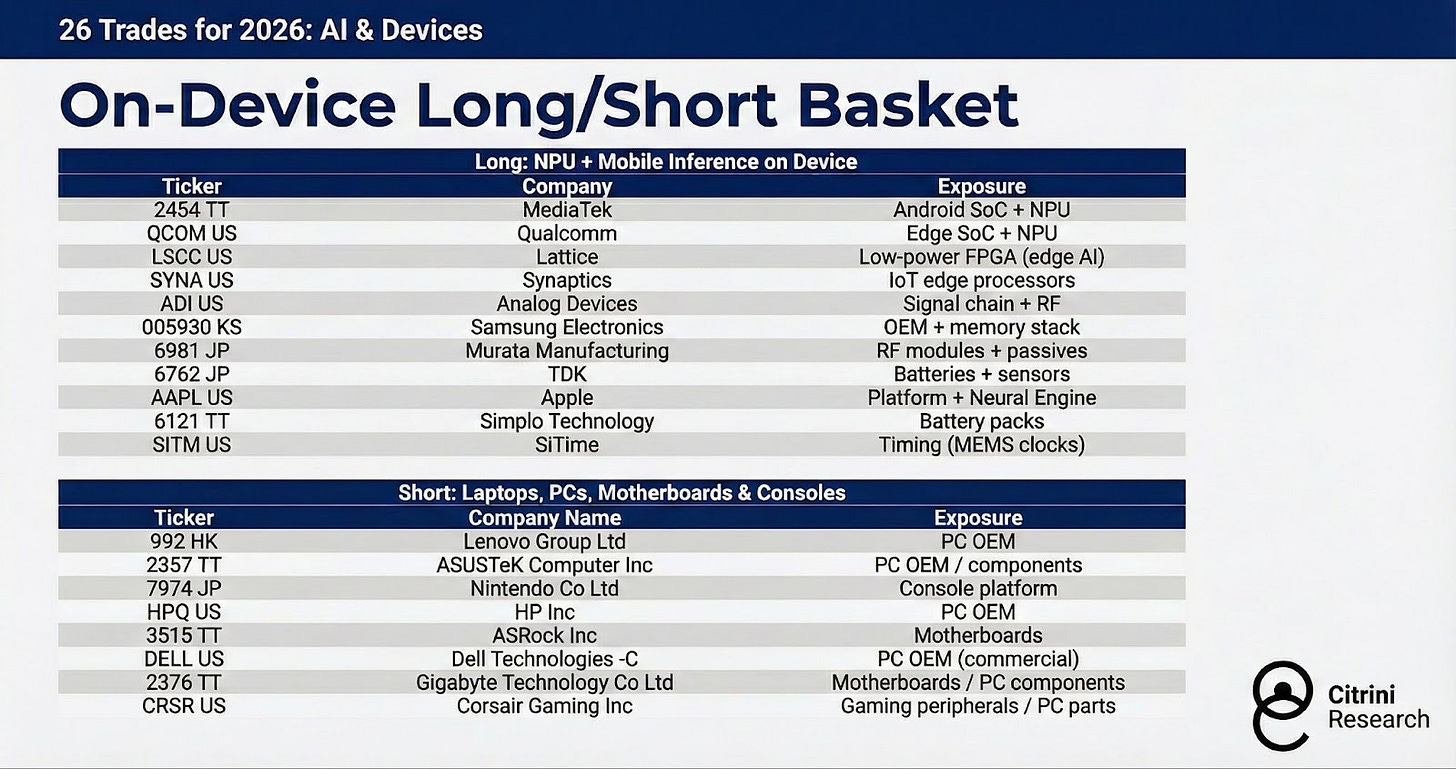

The Trade: Long Mobile Inference Enablers/Short Memory Squeeze Losers

I view the most pure and memory-risk neutral way to position for potential advancements in on-device inference for 2026 as being long the enablers of mobile inference-on-device and short the PCs, motherboards, laptops and consoles that get burned by memory prices staying high (not just DRAM but NAND too).

The cool thing is that a lot of the names that are enabling inference on device also have upside to cloud – Mediatek with next-gen TPUs, Murata Manufacturing’s (6981 JP) Multilayer Ceramic Capacitors (MLCCs), which we spoke about in last year’s 25 Trades, are in extremely high demand from data centers. A single AI server motherboard uses as many as 30,000 MLCCs, 10-times more than a crypto mining rig, and when crypto mining rigs hit the scene, they caused the most severe shortage of MLCCs ever.

In six months, our on-device inference names (equally weighted) have clawed back three years worth of underperformance. I think the next year, at least, looks a lot better for the companies providing the picks and shovels for AI inference at the edge than those implicitly short the memory requirements for AI either edge or cloud.

Back to how this memory cycle inevitably ends, though…

2a. All Chips Go to Heaven

As we fill Manhattan-sized datacenters with fast depreciating hardware, what happens when it’s finally time to chuck them? Call Sims Ltd (SGM AU).

Sims is an Aussie-listed scrap metal recycler with global operations, that trades how you would expect a metal recycler to trade: with a low multiple, cyclical and strong correlation to metal prices.

But a rapidly growing portion of Sims business is in IT recycling. Sims Lifecycle Services provides secure data destruction of servers and IT equipment and then either resells or recycles materials. This is a business that it has maintained for enterprise clients for some time (think, reselling corporate laptops), but it is now beginning to explode with hyperscaler demand from datacenters.

Over the past year, hyperscaler-driven recycling revenue increased by 78% from $112 million to $200 million, and management has guided towards large growth in the year ahead.

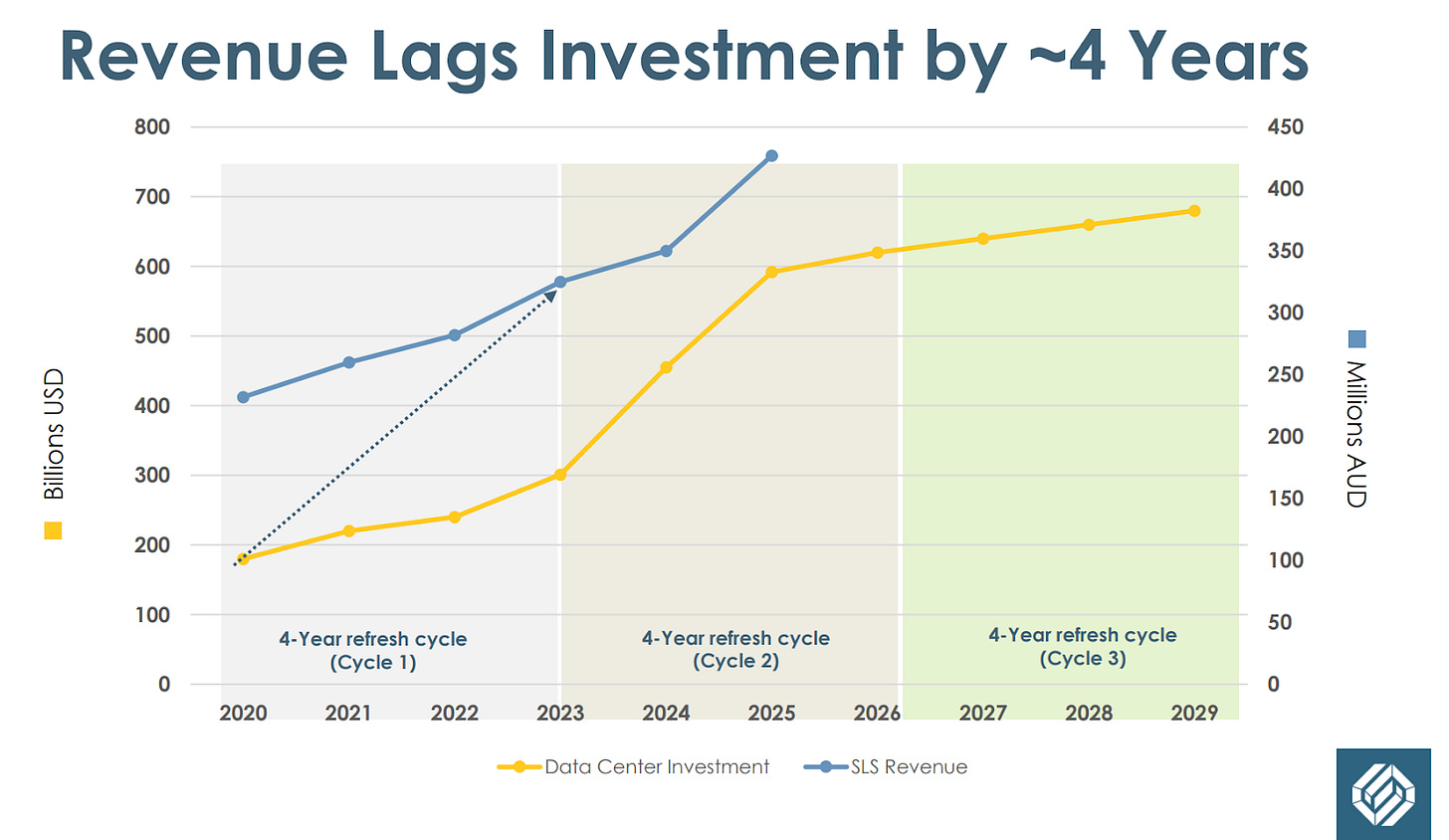

The thesis is pretty simple. Every single chip that goes into these massive halls today, is revenue for Sims, just with a couple years of lag. Every breakthrough in chip design and efficiency only speeds up the cycle. The surge in revenue that Sims is seeing today is linked to capital spending from several years ago – and of course we already know what has happened since.

Sims signs up hyperscalers on service contracts with staff co-located on site who are qualified in safely removing equipment and securely destroying data, which provides a stable baseline of revenue. Meanwhile the sheer volume of physical equipment that will need to be disposed of in the years ahead is set to explode.

The kicker is that Sims benefits from underlying commodities – things like gold, copper and steel – but also memory. Sims enables reuse, redeployment and recycling of DDR4 DIMMs and other high-value compute assets…which as you can imagine is a good business when memory prices go vertical.

Guiding towards $50 million of IT recycling EBIT in the 2026E and the tailwinds of the post-GPT splurge still on the way, this (significantly more attractive) segment of the business will likely overtake the core metals business in terms of (mid-cycle) profitability within the next several years. Further, there is plenty of room for a re-rate as the narrative shifts from cyclical scrap-yards to secularly growing datacenter demand.

3. Post-Traumatic Supply Disorder

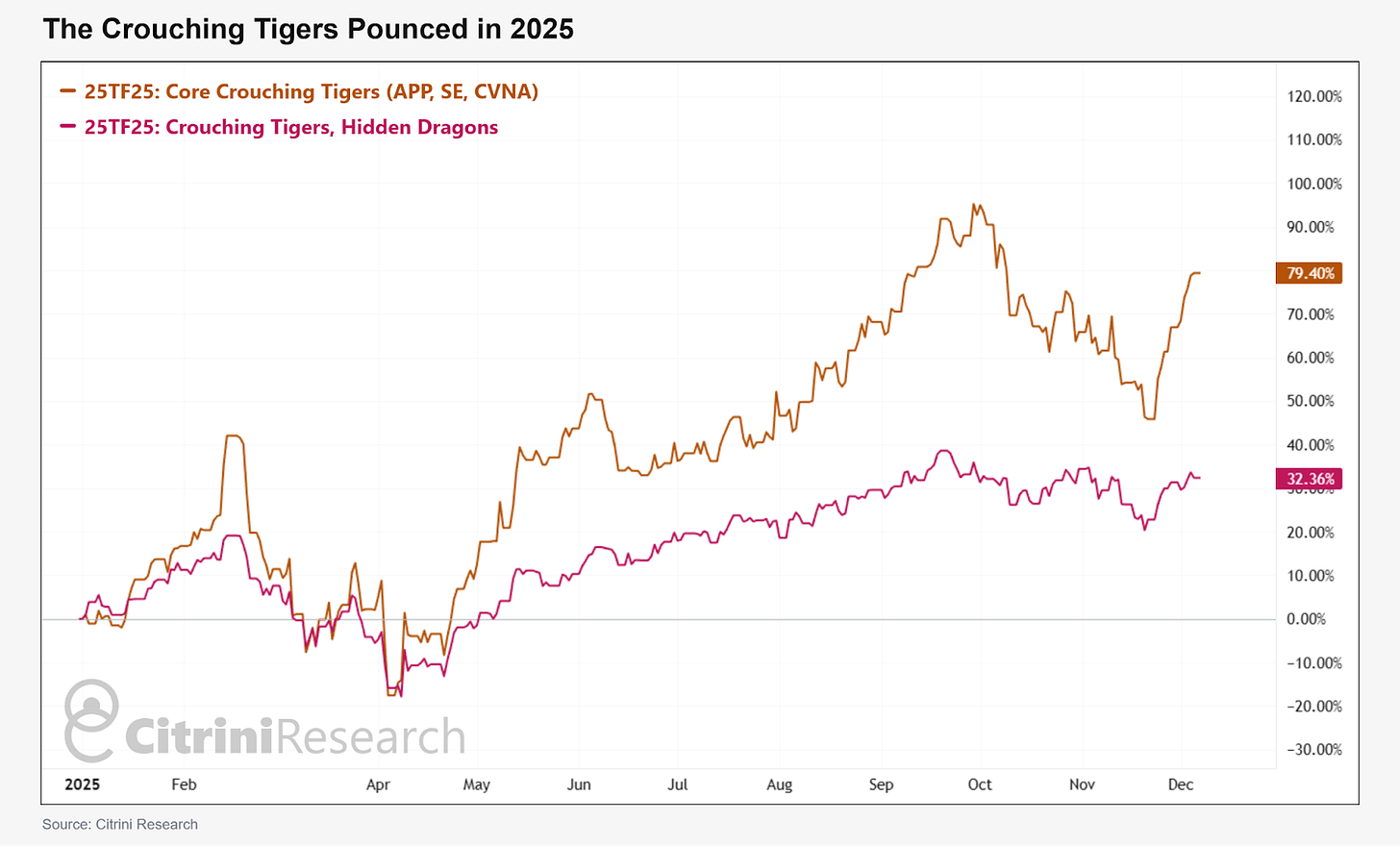

Last year, we had success by asking ourselves a simple question: what did the most significant and surprising outperforming stocks of the past year have in common? What thread connected 2024’s winners like APP, SE and CVNA – and could tugging on this thread help us find similar winners?

This culminated in one of our better performing themes. We proposed in “Crouching Tigers, Hidden Dragons” that the link was stimulus-era overbuilding, financed at zero rates, and aggressive customer acquisition meant these former darlings had infrastructure, data and brand assets that would be prohibitively expensive for any new entrant to replicate in a higher cost of capital world.

Meanwhile, they’d been left orphaned by their investor base who had been badly burned on them in 2022, but ready to leap as their models proved successful over a longer term.

Our core crouching tigers performed well, and our broad basket also outperformed significantly, led by Robinhood (HOOD US), Guardant Health (GH US), AppLovin (APP US), Lemonade (LMND US), Unity (U US) and SoFi (SOFI US).

We return to this well of inspiration to ask the same question of 2025. Where can one draw a common thread between some of the most surprising outperformers of the year?

Memory/storage names like Micron (MU US), SK Hynix (000660 KS) and Western Digital (WDC US) staged the seemingly-mythical back-half recovery and rallied between 170-260% year-to-date.

Gas turbine manufacturers Siemens Energy (ENR GR) and GE Vernova (GEV US) more than doubled in 2025.

It might be easy to generalize here and shrug off these names as simply rising due to trends in AI, but plenty of industries have AI upside and yet don’t top the list of 2025 YTD returns. We think there’s something else that puts these names in the top percentile.

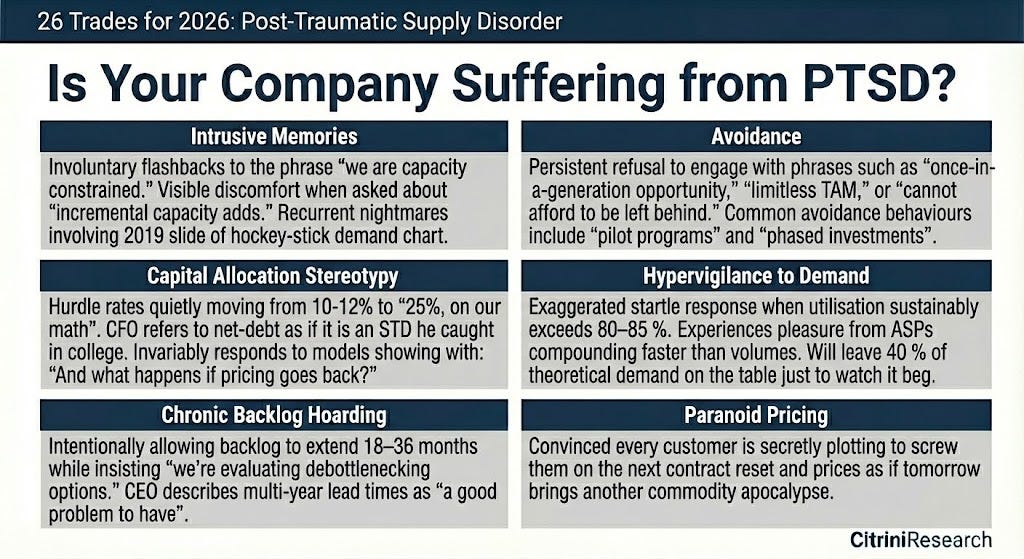

They all have PTSD.

That is… Post-Traumatic Supply Disorder. A cyclical corporate personality disorder of the capex-related-trauma variety.

This PTSD arises in industries that have rapidly increased supply in response to a sudden boom in demand, only to see demand fade, the market drown in oversupply and share prices collapse. These cycles, while painful, have a natural tendency to consolidate industries among the strongest players while instilling a capex discipline (if not outright fear) when it comes to expanding capacity in the future, even when demand surges. When customers eventually show up again, these companies simply raise prices and allow their backlogs and ASPs to explode.

Of course, we’re not applying a blanket “this time is different” to cyclical industries. And, naturally, any boom that goes on for long enough will convince even the most reserved teams to move to increase capacity – the cure for high prices, after all, is high prices.

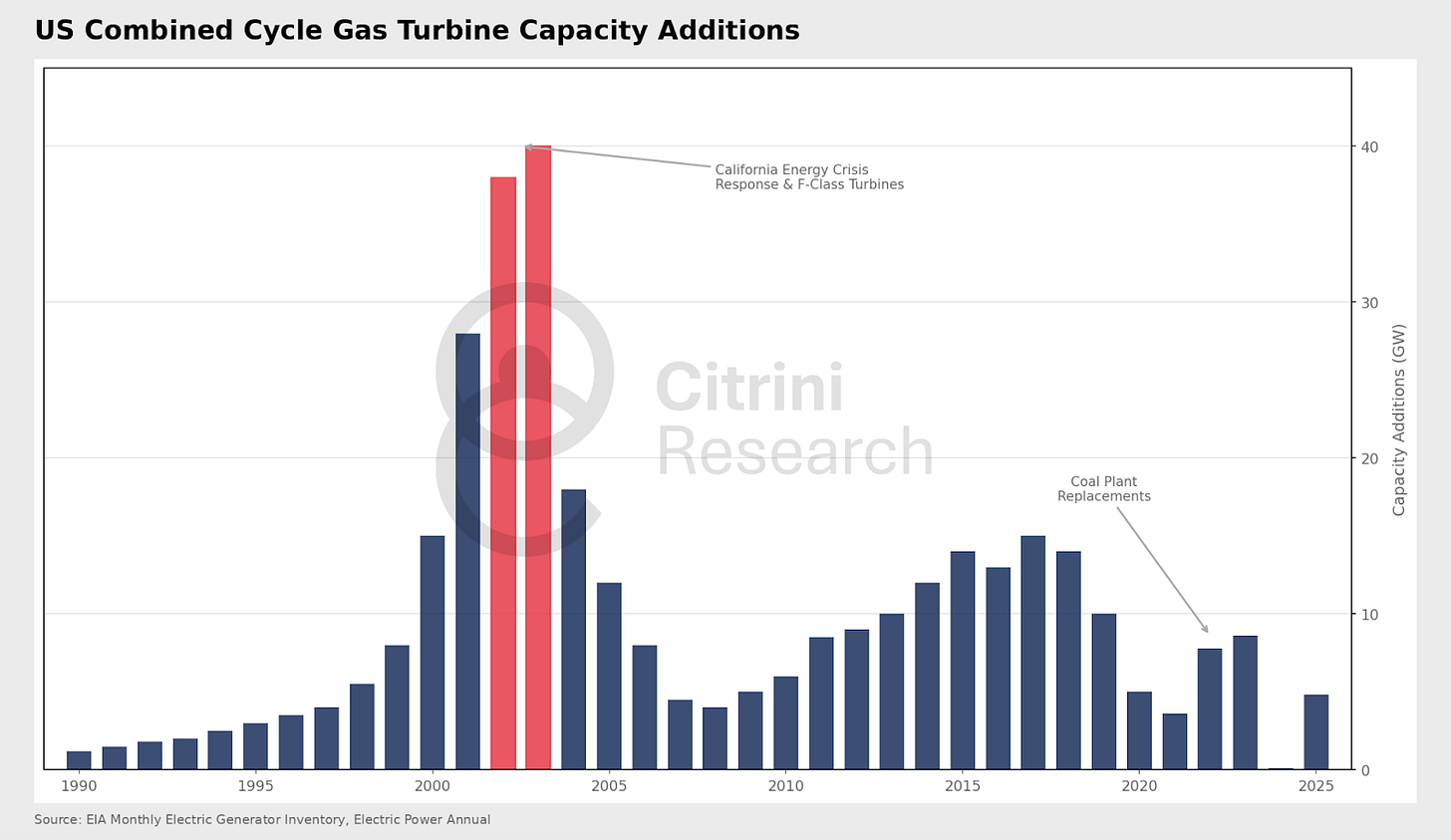

We’re on the lookout for the most remunerative varieties of PTSD across sectors. Natural gas turbine manufacturers were the perfect example this year. Gas turbine and grid OEMs went through two long and painful overbuilds: a major cycle in the mid-2000s and a second coal-gas switching resurgence in the mid-2010s as the shale revolution unlocked cheap gas domestically – each fading into troughs of demand.

Now, data center demands have led to record backlogs and stretched lead times, with only cautious capacity additions from a small oligopoly of GE Vernova, Siemens Energy and Mitsubishi (with Caterpillar picking up some spares in their Solar Turbines segment).

GEV’s most recent investor day shows this dynamic quite well. Despite demand for electricity being projected to “double,” GEV announced only a modest capacity expansion for heavy-duty gas turbines, increasing from ~20 GW to 24 GW per year by 2028. Meanwhile, they raised their adjusted EBITDA margin target from 14% to 20%. In a normal “pre-trauma” cycle, a manufacturer seeing demand double would rush to build new factories, often sacrificing near-term margins for market share. GEV is doing the opposite.

The same is true for memory. The notoriously cyclical industry has been through three severe DRAM/NAND collapses in the past 8 years. Now, supply is not responding. In DRAM, Micron canceled/delayed multiple capacity expansions, SK Hynix slowed capacity conversion, and Samsung moderated DRAM capex for the first time in over a decade. And even as the AI surge has pushed HBM demand to extremes, the players are extremely cautious about new capacity.

So where do we see this pattern emerging in 2026?

The Quantitative PTSD Screen

We’ve first attempted to capture this dynamic quantitatively with a screen of companies that meet the criteria to potentially become the next winners from this dynamic.

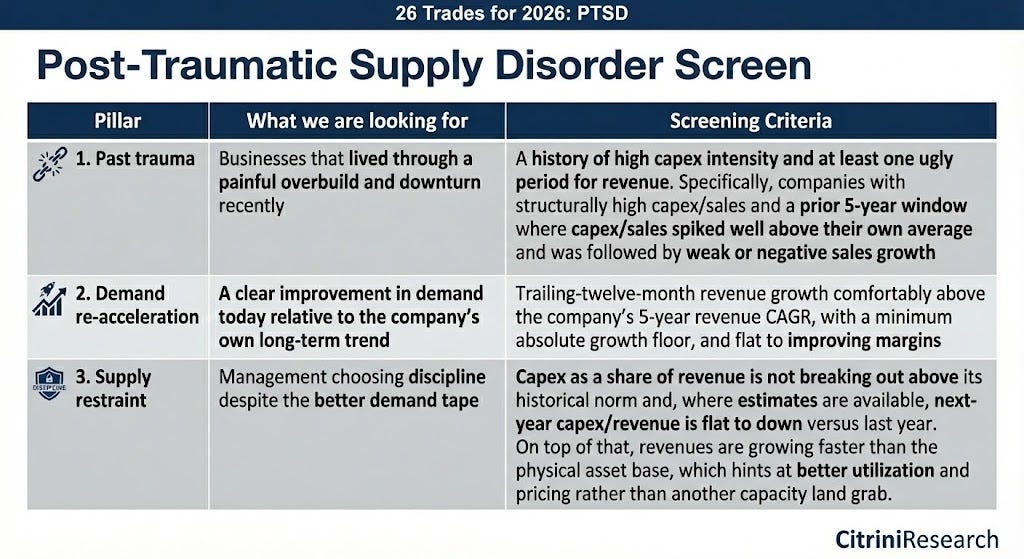

Here’s how we structured our screen:

In plain language: we first restrict the universe to cyclical businesses with a documented history of overinvestment and subsequent pain over the past ten years. Within that set, we look for companies where the demand side is picking up versus their own 5-year trend and EBITDA margins are stabilizing or improving. Finally, we keep only the names where capex intensity stays anchored; where capex to D&A suggests maintenance rather than greenfield expansion and companies are buying back shares and/or extinguishing debt.

We use a weighted scoring to determine demand score (i.e. is the company seeing demand for its products coming back) and capital discipline score (i.e. are they ramping capacity).

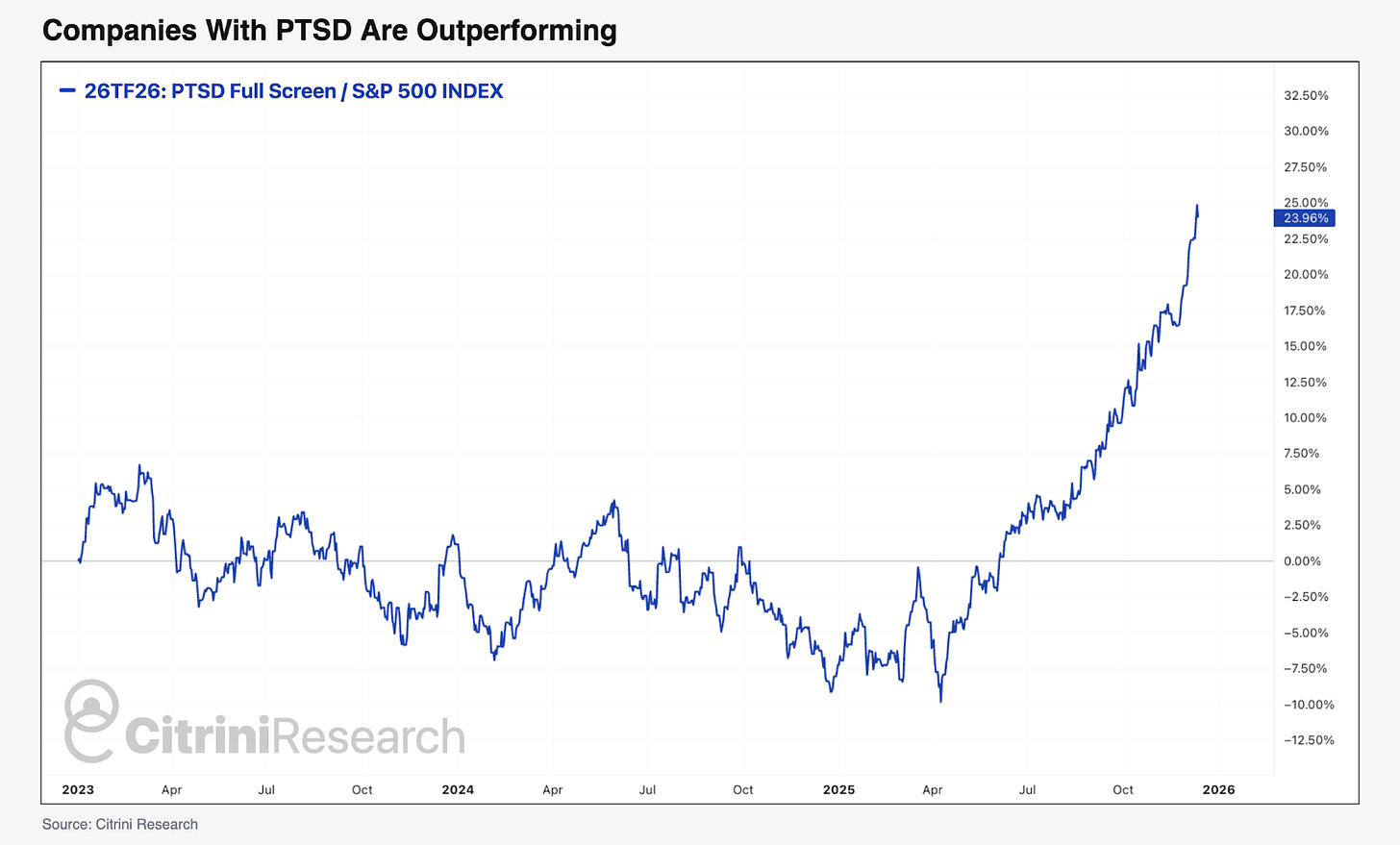

Coming out of the end of COVID (which we’ve simply marked as late-2022 to be safe), these companies generally underperformed as they suffered the consequences of the gluts they’d created. Recently, however, they’ve begun to significantly outperform.

Among our universe, we pick up a lot of companies that meet this description but are in businesses where they will really never have too much of a say over whether or not prices increase – competitive markets like precious metals and natural gas.

Newmont (NEM US), for example, meets our criteria for strong pricing, expanding EBITDA margins and capital discipline – but they are not a fit for our framework. They might be traumatized, they might be pushing through higher margins and being disciplined right now…but they are at the mercy of commodity pricing, and their competitors can always decide it’s time to flood the market.

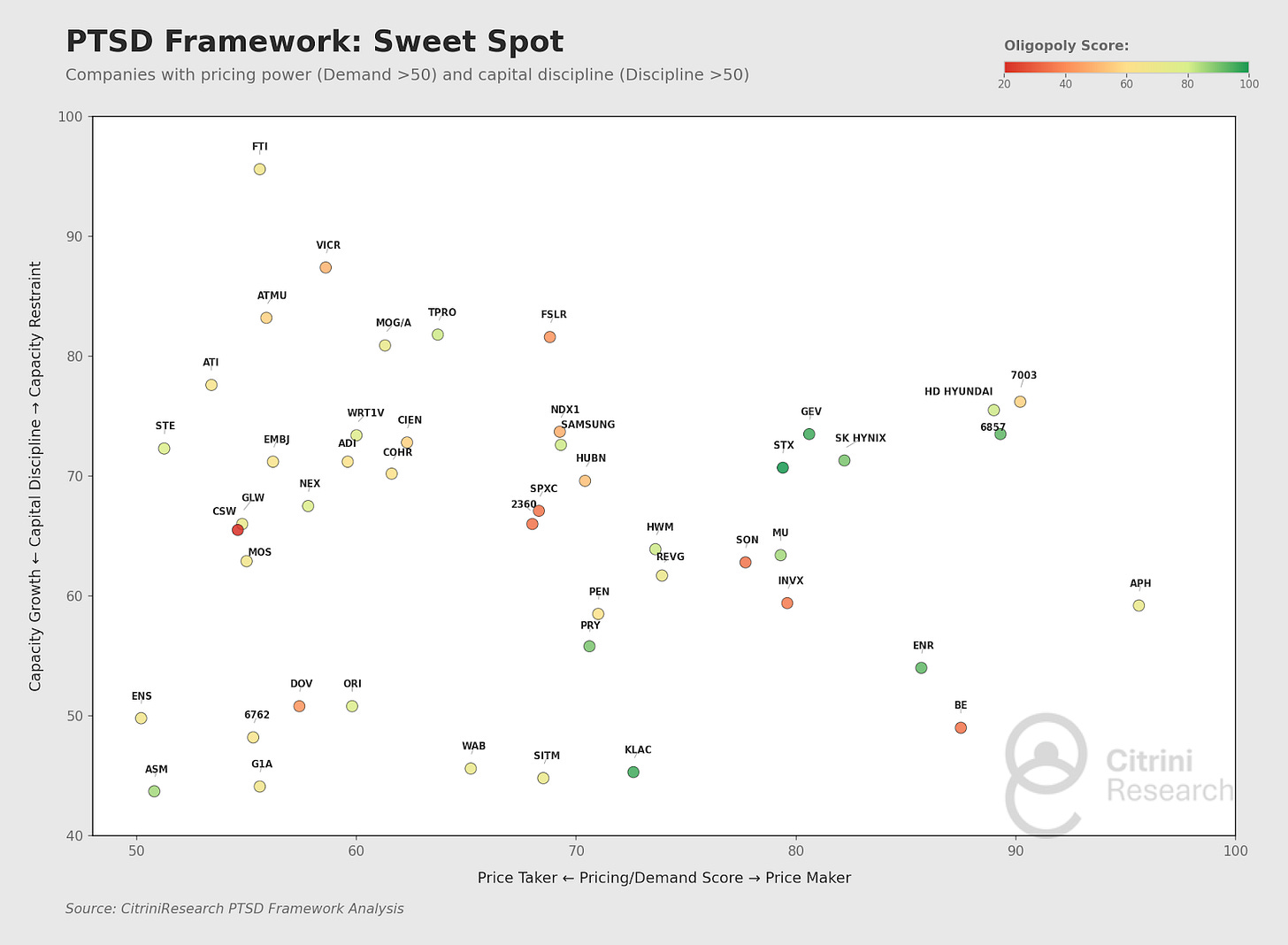

To narrow it down, we’ve determined the number of competitors either globally or regionally to compute an oligopoly score. All of these names show some of the traits necessary for this PTSD dynamic to occur, but for a true slam dunk you want the following:

Oligopolistic Market Structure

Relatively Recent Traumatic Peak-to-Trough Cycle

Early Signs of Demand Rebound

Capacity Holding Steady Despite Increased Demand

Here’s what it looks like when we filter only for names that score higher than 50 on our 0-100 oligopoly ranking:

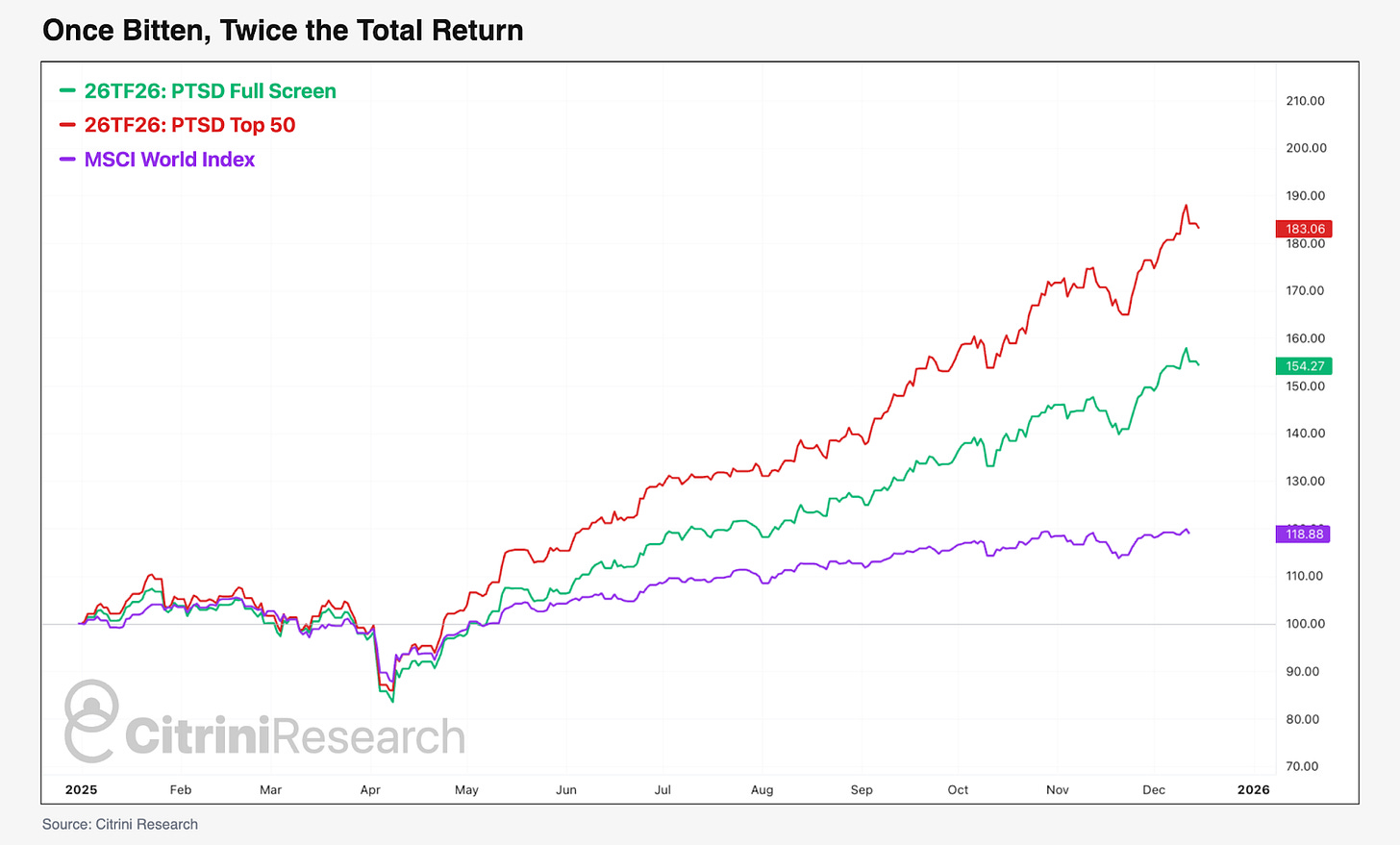

Incorporating the oligopoly score gives us an overall composite reading that combines demand, discipline, and market structure. The top 50 composite score list has significantly outperformed:

Even in those names that are already doing well, we’ve filtered for responsibility. These companies haven’t responded to forecasts of increased demand by ramping capacity – that makes it a lot easier to own them if you’re skeptical of those forecasts yourself.

For example, one of the highest scoring across our criteria is Siemens Energy (ENR GR). While Siemens has performed well, we see little reason it won’t continue to do so. Its SGT800 gas turbine is a superior product – providing lower heat rate through the combined cycle as well as lower EPC costs. If you’re lucky enough to get them, you’d expect to save up to $150M/yr on a similar sized (1.2GW) project to Stargate Abilene (compared to the turbines they’re utilizing from CAT).

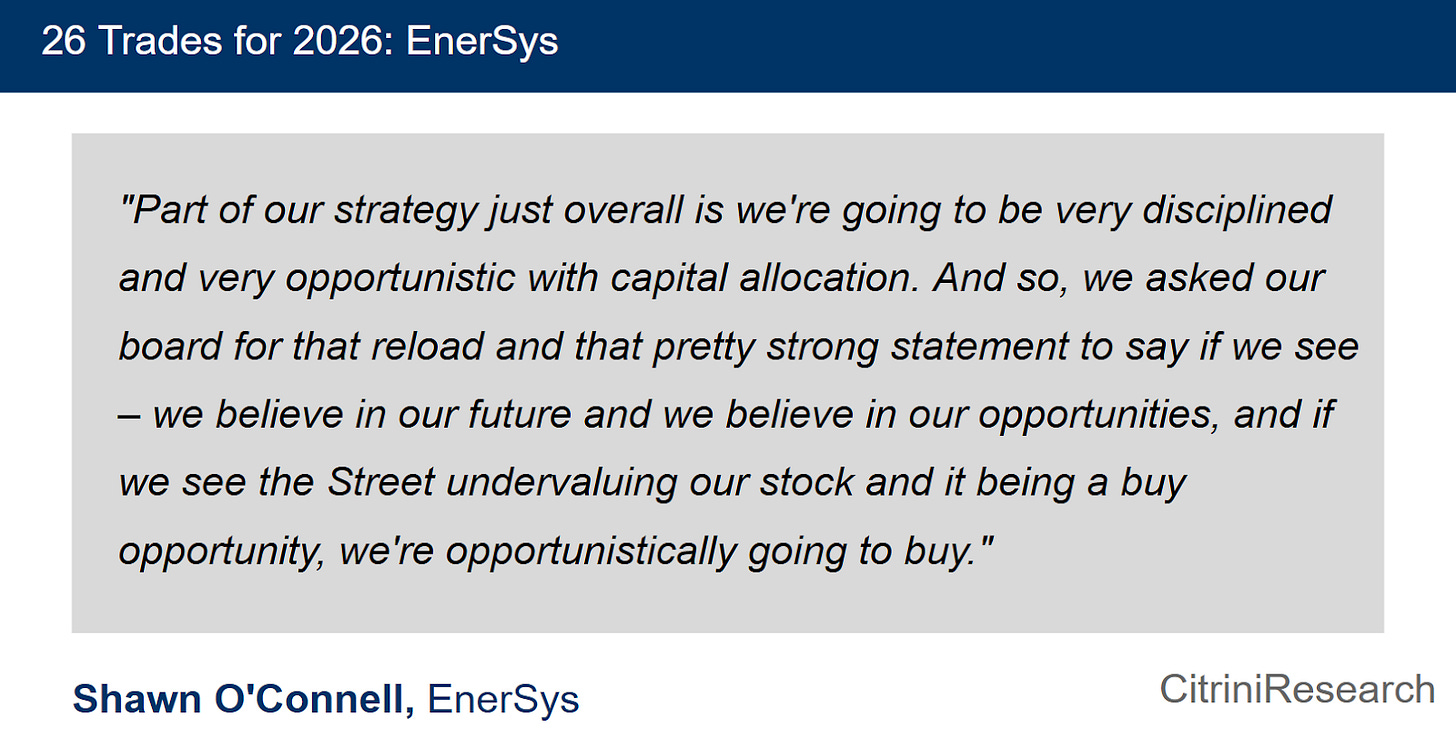

We also capture names that are seeing relatively new demand inflections – for example, take EnerSys (ENS US).

EnerSys had a long, grinding cycle in motive power and telecom batteries, then got caught between legacy lead-acid exposure and slower-than-hyped lithium/energy storage adoption. Management’s response has been textbook PTSD: talk a lot about “disciplined capital allocation” and then prove it by boosting buybacks by $1B, raising the dividend again, and emphasizing balance sheet strength while still funding selective growth projects.

That sets up a scenario where any upside surprise in data center or grid-storage demand is likely to drop disproportionately to EPS and buybacks, considering the stock trades at 15x trailing earnings.

This list is also picking up plenty of names that have yet to perform and are extremely well positioned to do so if they manage to continue navigating any pickup in demand.

Analog semis, for example, have yet to see broad demand pickup but a decade of brutal commoditization and the 2019 inventory correction traumatized the industry into radical capital discipline. TXN’s 300mm fab strategy and ON’s asset-light pivot mean capacity additions are now measured in years, not quarters, while automotive and industrial design-ins create sticky 7-10 year demand visibility with genuine pricing power.

Then there are those names on the screen which should likely be watched this year just in case demand picks up. Vestas Wind (VWS DC) for example scores very high on oligopoly, trauma, and demand has begun to normalize – but we haven’t seen a ton of cost discipline yet. This is an interesting but hated sector that could rally if these companies find religion.

Now, let’s look at the sectors where the numbers on the sheet aren’t as interesting as the real-world story:

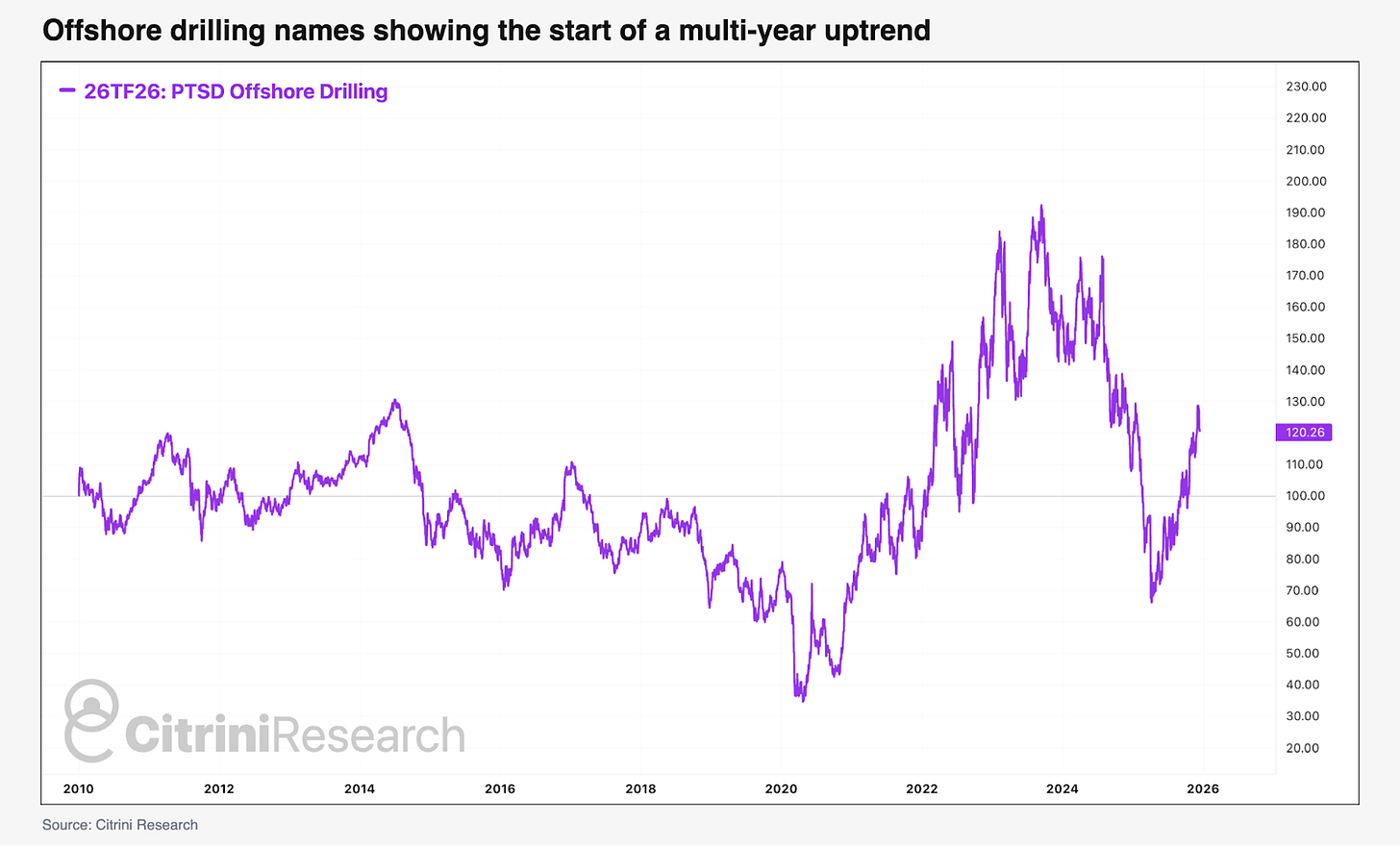

Offshore Drilling

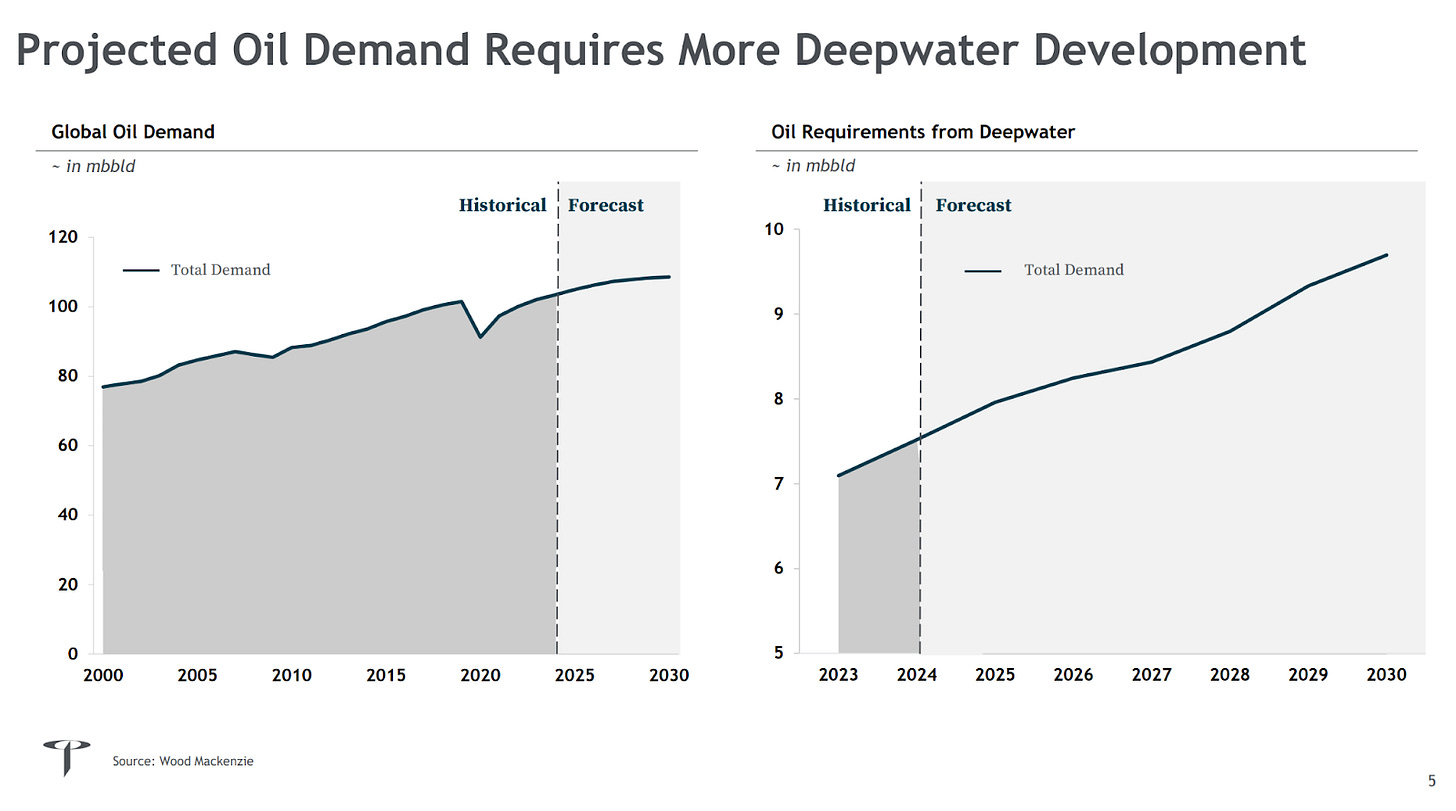

Offshore oil remains a critical source of new oil supply, particularly as shale production slows (due to rapid declines, capital discipline, and inventory concerns). The reality is that deepwater wells produce some of the lowest breakevens of new exploratory plays, and remain economic even under flat $60 per barrel long-term assumptions. As oil majors look towards the next decade of supply, they see stagnating shale, Russian declines and limited megaprojects in the Middle East. Offshore drilling – massive long-term, slow-declining projects capable of adding millions of barrels of incremental production – is needed to fill the gap.

Offshore is poised to take share structurally, not cyclically, and this remains true regardless of short-term oil prices.

Meanwhile, the offshore drilling industry hasn’t even remotely recovered from the 2013-2014 oil price collapse and new supply is non-existent. The most recent new drillship was delivered in 2021 and there are zero new drillships in the pipeline. Even if an order was placed today, it would be unlikely to reach the market until at least 2030.

With a truly fixed supply, drillship day-rates have increased substantially over the past several years as the post-COVID recovery has restarted these long-lead projects. The contracting drilling companies that have survived (or were restructured) through the depression now hold the cards.

With share prices showing the start of a multi-year uptrend, even a little bit of incremental oil demand could send Transocean (RIG US), Valaris (VAL US), Noble (NE US), Seadrill (SDRL US), Helmerich & Payne (HP US) and Nabors (NBR US) much higher and result in less-than-expected responses in terms of production.

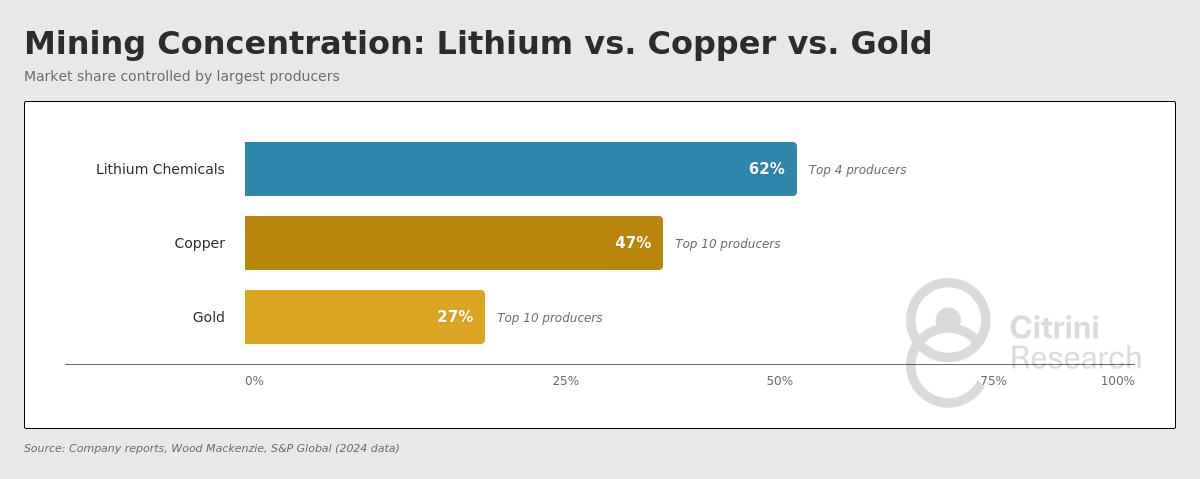

Lithium

Lithium has just gone through a textbook boom/bust cycle. Prices went from “new oil” euphoria to an 80%+ collapse as capacity came online and slower EV demand showed up.

In response, Albemarle and others are cutting capex, re-phasing or deferring large projects, and focusing only on near-complete or highest-return assets. Multiple players flag explicit capex reductions, layoffs, and project delays with marginal producers shutting-in supply. At the same time, long-term EV and storage demand is still rapidly growing. This is how the next shortage usually begins.

This group is earlier in the PTSD arc. Some names are still in the “trauma and retrenchment” phase rather than the “enjoying tightness” phase, and while pricing is commoditized and these aren’t really oligopolies Chinese anti-involution policies could change the market structure - production is still very concentrated in the biggest producers like SQM (SQM US), Elevra Lithium (ELV AU), Tianqi (9696 HK), Albemarle (ALB US), Rio Tinto (RIO AU), and Ganfeng (1772 HK).

Copper

The 2000s supercycle ended with a nasty capex hangover. A lot of large projects came on just as China slowed, and balance sheets and equity holders wore the pain. Since then, majors have been extremely reluctant to approve new greenfield copper megaprojects. The talk is “value over volume,” brownfield expansions, and M&A for optionality rather than a new Escondida-style build.

Now, electrification and data center driven grid buildouts argue for structurally higher copper demand but corporate boards are still cautious on mega-projects, instead opting for marginal expansions, de-bottlenecking, and capital returns. Nobody in the industry is ready to model out the kind of capacity this will require.

Unlike turbine manufacturers, copper miners are price-takers rather than price-makers. However, like lithium, copper production is much more concentrated among the large producers.

The top ten producers control roughly half of global mine supply, but that headline number undersells the concentration where it actually matters: incremental supply. The handful of companies capable of financing, permitting and operating a world-class greenfield project can be counted on two hands. Building a new Escondida today, if you could even find one, costs $5-7 billion minimum (roughly the market cap of a mid-tier miner), takes over a decade to permit, and should assume an average 79% cost overrun according to McKinsey.

We’re looking at names like BHP Group (BHP AU), Freeport-McMoRan (FCX US), Southern Copper (SCCO US) and Antofagasta (ANTO LN).

Trucking

Less-than-truckload (LTL) freight is a service, not manufacturing, so the discipline dynamic is a bit different. However, we see some threads of similarity to those names in our PTSD sweet spot. Trucking was the poster-child COVID supply-shortage story that quickly flipped oversupply as independent contractors flooded the market, goods demand whipsawed and freight rates collapsed. The impact of the trade-war driven volume disruptions in 2025 only kicked the industry while it was down. The fallout has resulted in a wave of freight bankruptcies that is consolidating the industry.

While few would call the current trucking market bullish, the reality is that a significant amount of slack has already been removed from the system. Further, the crackdown on commercial driver license (CDL) standards under the Trump administration has led to the significant contraction among the “swing” supply that helped alleviate the COVID crunch. These dubious CDLs were highly concentrated among smaller independent contractors that likely were far more lenient in their driver profile than large publicly traded names.

But now, we are seeing signs that the trucking market may indeed be moving in a positive direction with holiday traffic, tender rejections and freight rates picking up substantially over the 2025 trend.

To the extent a turnaround occurs, the gains will likely accrue to the larger established and publicly traded players – names like Old Dominion (ODFL US), JB Hunt (JBHT US), Knight-Swift (KNX US) & TFI International (TFII US). Additionally, among the brokers, there’s the higher potential of AI implementation automating processes and driving operational efficiencies (as prominently highlighted by CH Robinson (CHRW US), we see no reason XPO (XPO US) couldn’t follow suit).