The New WFH (War From Home)

Missile Defense, Counter-Unmanned Technology, Electronic Warfare, and Surveillance

Introduction

Modern warfare has evolved.

Cheap drones are torching billion-dollar fortresses and countries are waging direct warfare from thousands of miles away. Last year, Houthi drones successfully blocked global commerce through the Red Sea despite US carrier strike groups stationed in the region. More recently, Ukraine unleashed a surprise attack of 104 drones 800km deep into Russian territory, lighting up the Kirishi refinery and significantly damaging Moscow’s aerial assault capabilities.

Weeks later, Israel ran the same playbook, using smuggled drones (along with traditional assets) to wreak havoc on Iranian nuclear facilities and military targets as a part of its broader “preemptive strike” on the country. Tehran responded to Israeli air strikes by hurling hundreds of Shahed drones, cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles towards Tel Aviv and interior targets. Israel’s missile defenses have successfully blocked a large majority of the strikes, but at roughly $45,000 per Tamir shot such defenses are not free or unlimited. Iranian ballistic missiles have continued to penetrate the Iron Dome, causing direct damage on civilian and military installments. The U.S.’ involvement began with a USAF crew that never had feet on the ground anywhere outside of Missouri.

Iran, the US and Israel are ostensibly “at war” (or at least in conflict). This is occurring with no troops deployed on foreign soil and each country thousands of miles away from the other.

What becomes clear across these various theaters is a shift in the strategy and tactics of modern warfare that challenges the traditional views of asymmetry. We have entered the new WFH, that is, “War from Home”. The implications: for under-resourced countries, a new form of leverage, for countries with lots of resources, a wake-up call.

This pattern recurs throughout history: technology wins wars. Great powers that rely on yesterday’s tactics can be quickly humbled. Consider France’s Maginot-mentality crumbling to the German Blitzkrieg. Or the linear forces of Britain falling to the guerrilla colonial revolutionaries. Raw firepower can often be duped by agility, communications, distribution, and innovative tactics – perhaps the lack of firepower is even the constraint that leads to such developments (a cross-theme callout to China’s GPU-starved Deepseek advances).

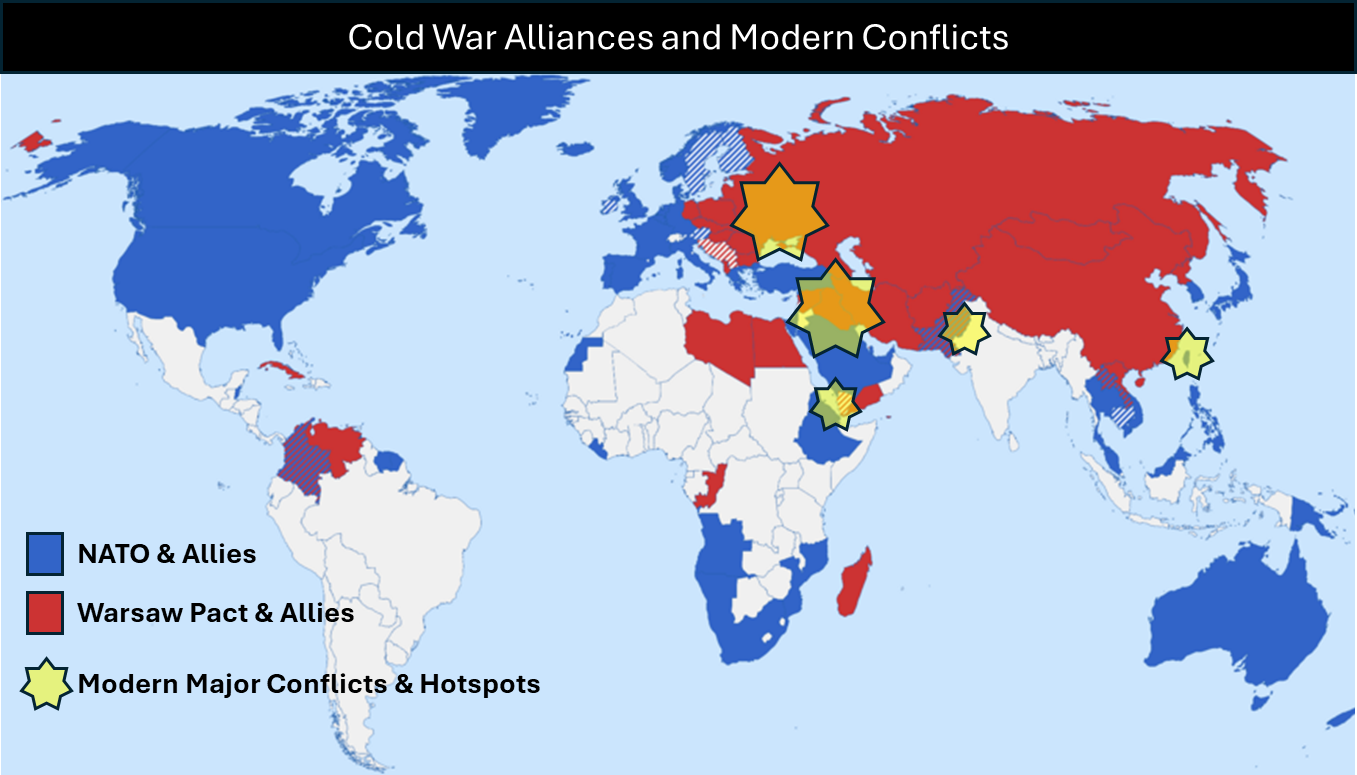

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, war has been mostly limited to proxy battles in underdeveloped nations or US occupations. This regime is quickly unraveling; hot wars between major military powers are developing, the battlefield is being rapidly re-defined, the importance of “the best offense is a good defense” has never been more stark.

In short, the way we wage war has gone through an inflection point.

Why should investors care?

First, we see a massive fiscal realignment towards defense spending in the US and globally (among NATO members).

Second, we see military superiority being rapidly redefined by technology.

Third, we see the hard catalysts of well-armed adversaries – Russia pushing into eastern Europe, Israel/US fighting Iran and its proxies in the Middle East, and China’s long-standing intention of reunification.

For the first time ever, the FY2026 US defense budget blueprint has broken the $1 trillion ceiling. While increased spending will be a boon across the military industrial complex, much of the new spending will be directed towards new technology. The next big defense cycle is electronic.

Nobody is under the illusion that the U.S. and Israel are not at the top of the list when it comes to offensive capabilities. However, with the risk for radical factions and guerrilla attacks climbing every day, defending against low-cost, high-potential-damage technology becomes increasingly important.

The Pentagon recognizes the changing landscape of modern war. In a world of UAVs, satellite-based weaponry, and intercontinental hypersonic missiles, the modern battlefield is one that prizes technology and industrial production capacity over flesh and blood. The current House reconciliation bill, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), adds $13 billion for missile defense and authorizes a “Golden Dome” space layer, while singling out a $693 million C-UAS fund that can be drawn down at will.

We originally published our Electronic Defense and Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems (C-UAS) as part of our thematic watchlist, “25 Trades for 2025.” Now, we’re seeing Trump’s fiscal realignment and geopolitics converge to create a durable next leg up.

One of our most successful thematic primers was Fiscal Primacy in September 2023, published long after the trio of Biden discretionary spending bills had been signed into law. The success was not in predicting the weather – but simply noticing that it was raining.

While nothing is “set in stone” yet with regards to defense spending, we think this specific area of defense should see bipartisan support. And since some companies will be the recipients of that money, we’re heads down in defense for now.

Fiscal Realignment: Defense Budget

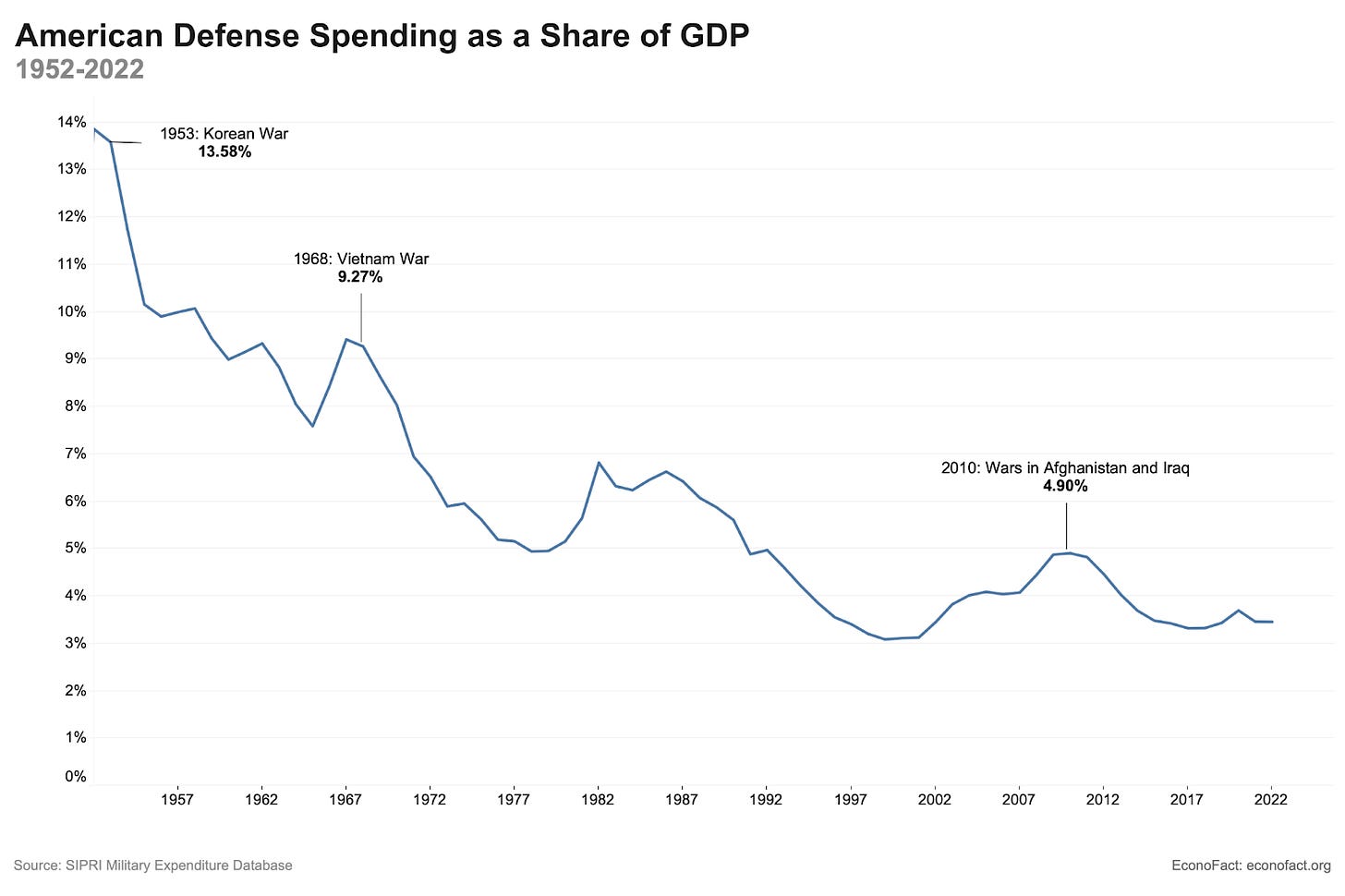

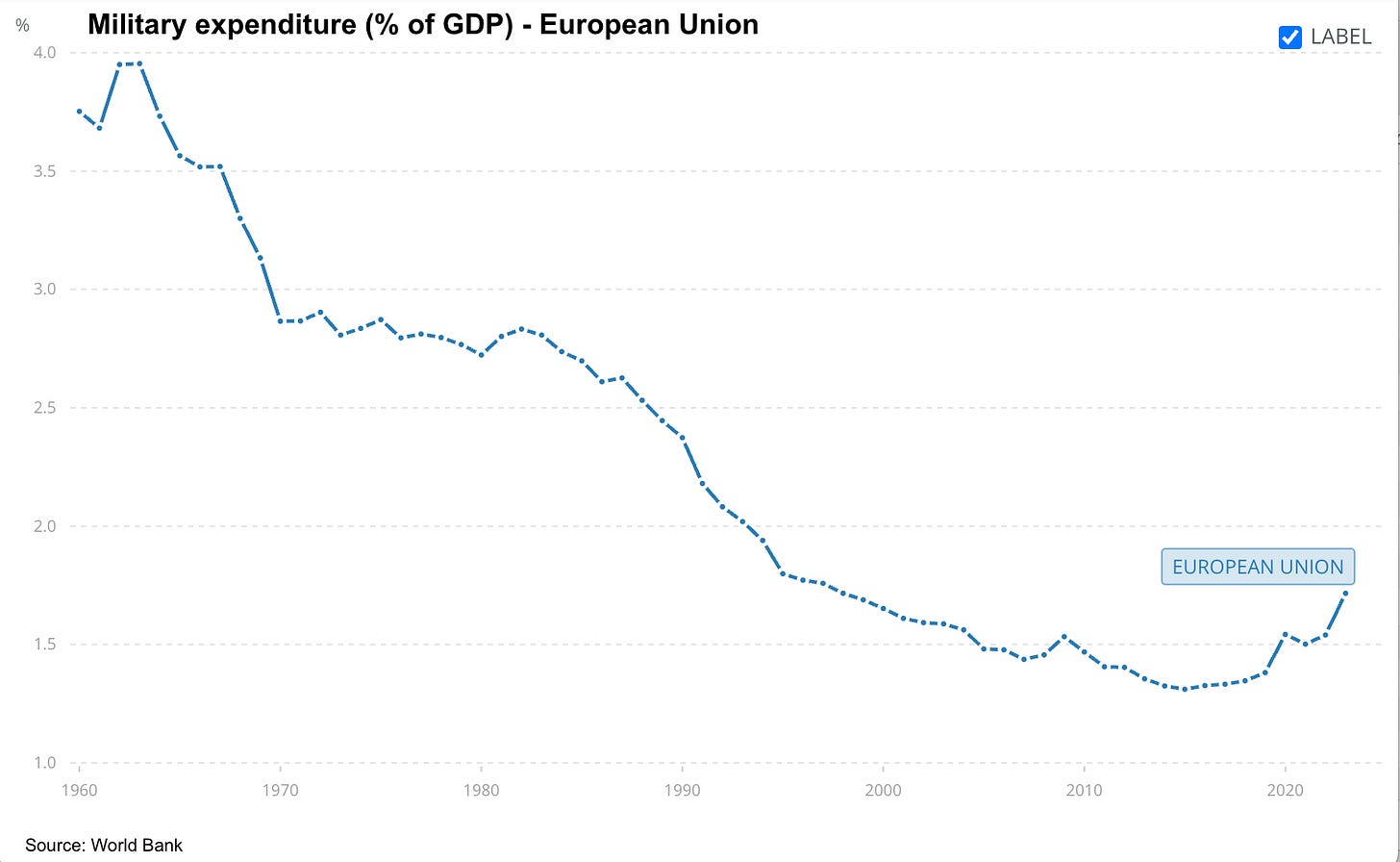

Despite tipping the scales over $1 trillion, defense spending as a percentage of the overall economy has actually declined for decades – first with the end of the “hot war” era from WWII to Vietnam, and even more in the warming of global relations in the post-Cold war period…

But threats to military hegemony demands an increase in spending, not a decrease.

Unquestioned superiority is a financially efficient form of deterrence. But as rival capabilities grow, the threat of retaliation alone is insufficient. And as technology continues to shape the landscape, old tricks must be replaced. As rival capabilities threaten the US interior, the idea of national defense takes a newfound, literal meaning.

While the early headlines from the Trump administration fixated on federal jobs cuts and DOGE, the reality is that the fiscal cliff isn’t coming.

Rather than a fiscal headwind, we see an enormous fiscal realignment. The fiscal impulse is taking a wartime footing. Indeed, re-industrialization via militarization is a fairly well proven playbook, even if its implications may be unsettling.

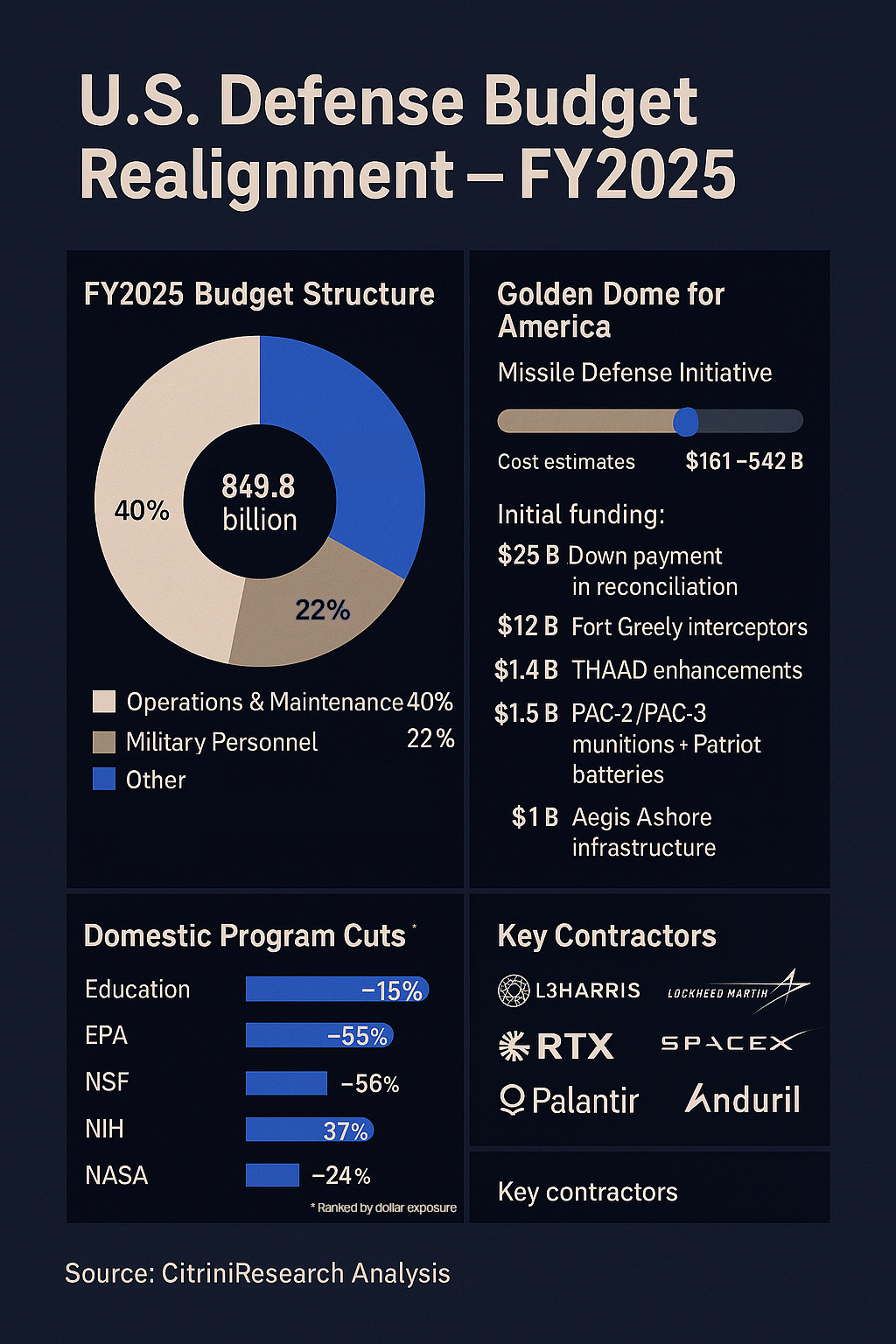

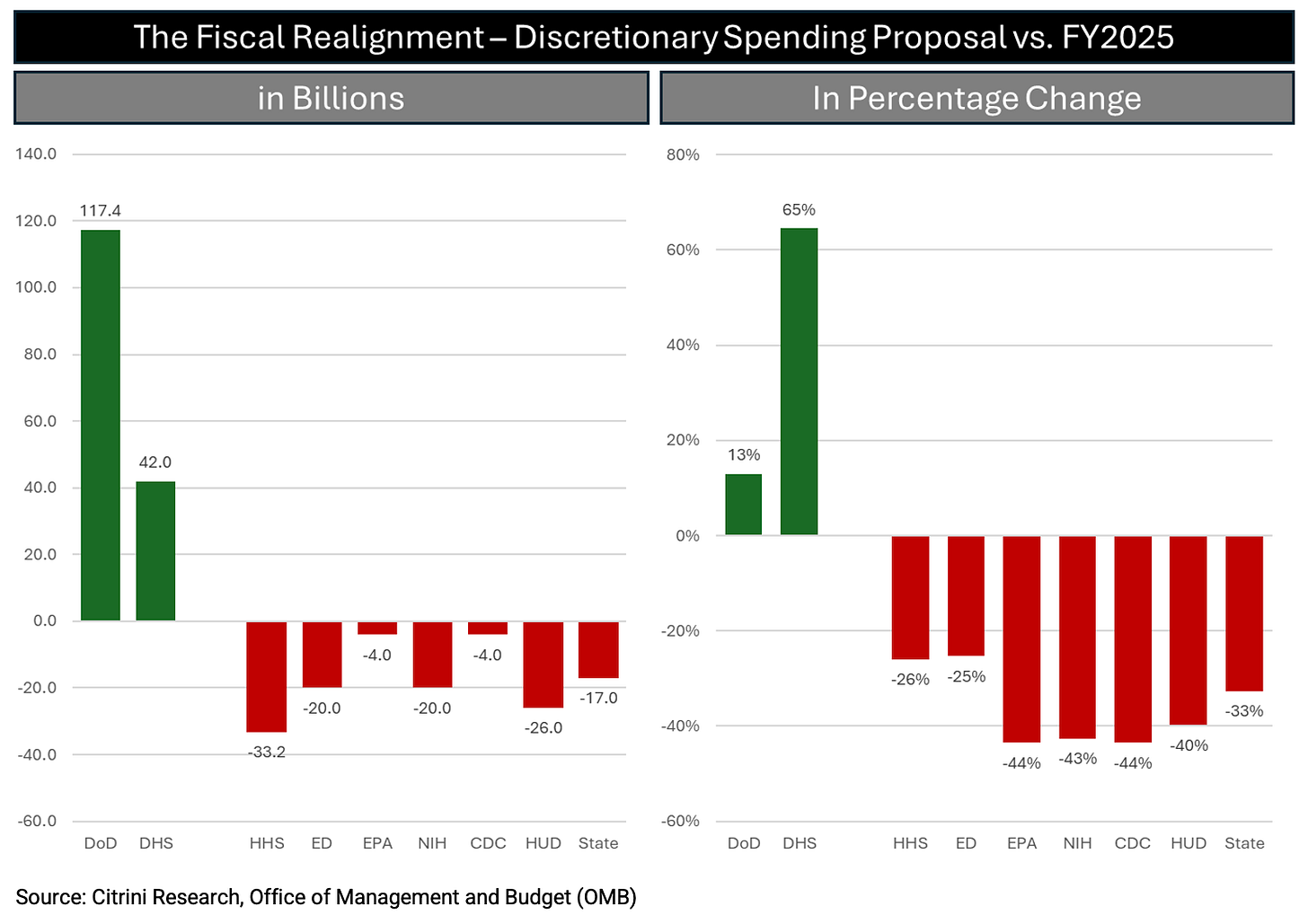

Trump’s “skinny budget” – the discretionary spending blueprint in early May – called for a massive boost to the Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and equally seismic cuts to every other agency – targeting income assistance, education spending, scientific grants.

While this realignment bodes well for military contractors, the top-line changes likely understate the impact. Not only is total spending likely to increase, but an internal shift within the DoD will lead to a disproportionately large increase in procurement, technology development programs, and hard asset contracts.

Today, half of the DoD budget goes towards personnel expenses – both current military and pensions. Meanwhile, many high profile service contracts have been given to consultants.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth has made it clear that all spending without a clear battlefield application is on the chopping block, including military personnel of the highest level. In early May CNN reported on a Pentagon directive to cull generals and officers:

“US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has ordered senior Pentagon leadership to cut the number of four-star generals and admirals by at least 20% across the military, according to a memo signed by Hegseth…

The memo also directs the Pentagon to cut the number of general officers in the National Guard by 20%, and to cut the total number of general and flag officers across the military by 10%..”

And while a previously announced goal of 8% “cost savings” outlined by the SecDef at the start of the administration briefly spooked the market, the reality is that any cost savings in administration and operations will likely be redirected towards procurement.

Now, we’ve moved beyond a simple wishlist to legislative text. This week, the Senate provided its markup to the House’s OBBBA text – setting up conflict between the Republican party as the chambers attempt to bridge the gap. But even as the final law remains uncertain, the biggest gaps relate to tax cuts, tax credits, SALT deductions, and cuts to medicaid.

The total $150 billion allocation to discretionary defense spending remains unchanged.

Instead, the Senate version makes modest shifts to line items – decreasing the shipbuilding budget with offsetting increases to munitions, readiness, technology and nuclear deterrence. Ultimately, we expect a sizable defense budget increase to pass, with the funds allocated towards the highest priorities. In particular, the emerging vectors of warfare – missile interception, drones and drone defense, electronic warfare, and intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) – will be the key beneficiaries.

We don’t view this as a typical red-shift on the budget seesaw, but rather a more significant turning point in geopolitics, technological competition, and the global balance of power.

And it’s not just the US. Defense spending as a percentage of GDP in the EU has already begun inflecting higher and will only grow from here.

Fiscal Asymmetry: Sticker-Shock and Awe

At the center of the offense has become cheap, modular, even plentiful.

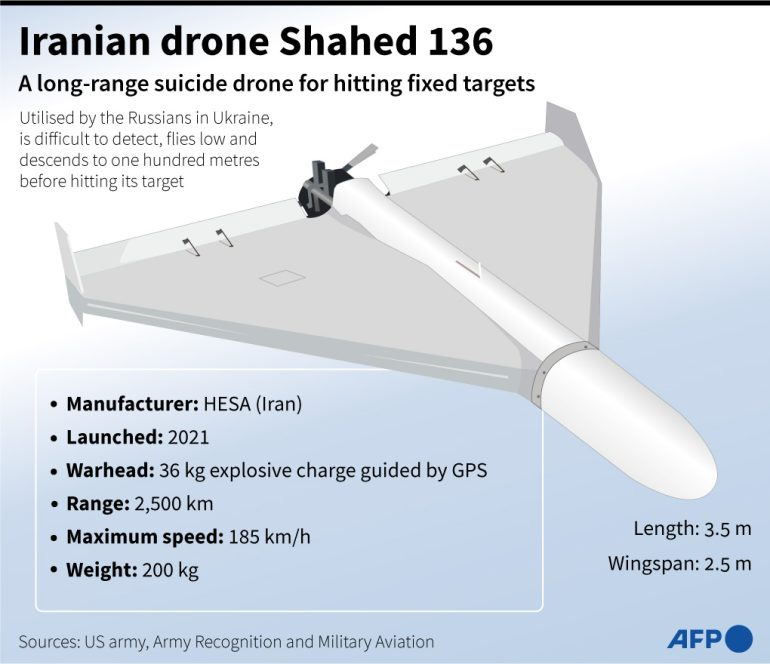

One-way loitering drones or “kamikaze drones” like Iran’s Shahed are being used extensively by Iran (and its proxies) in the Middle East and by Russia. With GPS guided ranges as far as 2,500km and with a price estimate as low as $20,000, large swarms are cheaply obtained and can overpower traditional air defenses either through physical or financial attrition.

Precise Short Range Missile Defense Systems (SHORADS) like US AMRAAM (AIM-120) or the German IRIS-T can easily extinguish a single threat, but at a cost of 20-50x per drone (representing a high cost-asymmetry), these advanced missiles simply aren’t a viable solution. Moreover, swarms can be used to temporarily overwhelm interception capabilities, allowing ballistic missiles to strike targets unimpeded, as we have recently seen in Israel.

These Iranian-made Shaheds have severely agitated some of the most capable US military assets. Earlier this year, Houthi swarms severely stressed the interception capabilities of US naval strike groups in the Red Sea, which expended their supply of AIM-9/AIM-120 missiles ($500K–$1M) and SM-2 interceptors ($2M), forcing the ships to use guns as last resort, and forcing the group to “high alert” status for two full weeks.

Meanwhile, First-person view (FPV) drones – quadcopter drones that look like hobby drones with bombs strapped to them – provide their own defense challenges. Not only are they remarkably cheap (<$1,000), but their size allows them to be smuggled deep inside enemy territory, and unleashed from containers or truckbeds.

As seen from Russia to Azerbaijan to Iran, such attacks can take out highly expensive tanks and airplanes at an extraordinarily disproportionate cost.

As these techniques become commonplace, nations are both rushing to increase their own production capacity while also adapting their defensive capabilities.

From a cost perspective, simply gunning down the drones has proven a cost-effective method of choice for the Ukrainian army, but more comprehensive and efficient solutions are required for a potential much more extreme onslaught. These include kinetic defenses like gatling guns, airburst rounds, and interceptor drones, but these strategies can still be asymmetrically costly.

Here, electronic warfare significantly levels the playing field. Direct energy weapons (lasers) have “unlimited” ammunition (provided integration into a reliable power source) and a very low cost per round. For example, Israel’s Rafael Advanced Defense Systems unveiled a high-energy laser weapon system, LITE BEAM, at the 2024 Association of the United States Army (AUSA) event in Washington, D.C. designed for the rapid and precise neutralization of aerial threats, including drone swarms.

Meanwhile disrupting electronics and navigation may prove even more efficient at countering mega swarms. Radio jamming and spoofing can interrupt or redirect communication and navigation. High-power microwaves can release EMP-like pulses to disable electronics. Cyber-warfare could infiltrate software at the source.

A comprehensive solution requires all of these methods working together. Western militaries are now in a mad dash to do just that.

The Time is Now

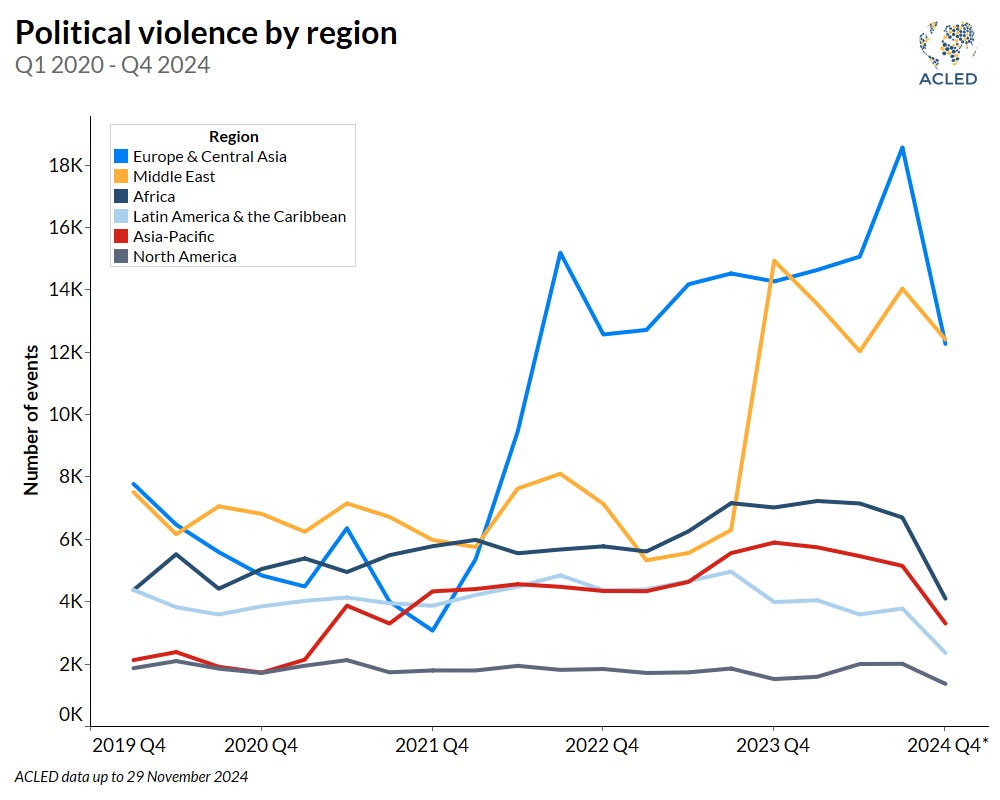

Though disconcerting, the ultimate catalyst here is necessity. For the past three decades, the major global powers have mostly refrained from direct hot conflict with each other. That era is over.

It doesn’t take a historian to recognize that today’s largest military conflicts and tensions trace the seams of the Cold War alliances. We are primed for extraordinary military spending and competition.

It seems almost undeniable that there is more legitimate military tension in the world today than at any point since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. American-provided intelligence and weapons are being used to strike deep within Russia’s interior. Trump seems to be edging ever closer to “officially” entering conflict with Iran. India and Pakistan’s simmering spat has boiled over into dog fights.

Above each of these conflicts is the great, looming question – China. A full blown kinetic war with China is, almost without question, the greatest risk to US national security. China’s immense industrial capacity – its dominance in drone technology and supply chain, impressive hypersonic capabilities – represents the most formidable foe since the Cold War, perhaps even earlier.

While we should hope to avoid these outcomes, hope is not a substitute for preparedness – this is the key message being delivered from the top down.

A new era of true multipolar military competition has just begun.

Four Pillars of the Modern Shield

While increased defense spending will undoubtedly trickle throughout the military industrial complex, the greatest rate of change will be more focused. The categories of most significant investment are those of the most pressing vulnerabilities – where technological advancements create new asymmetry, where new frontiers demand new outposts, where risks give underdogs a fighting chance. These are the four pillars of the modern shield.

Missile Intercept

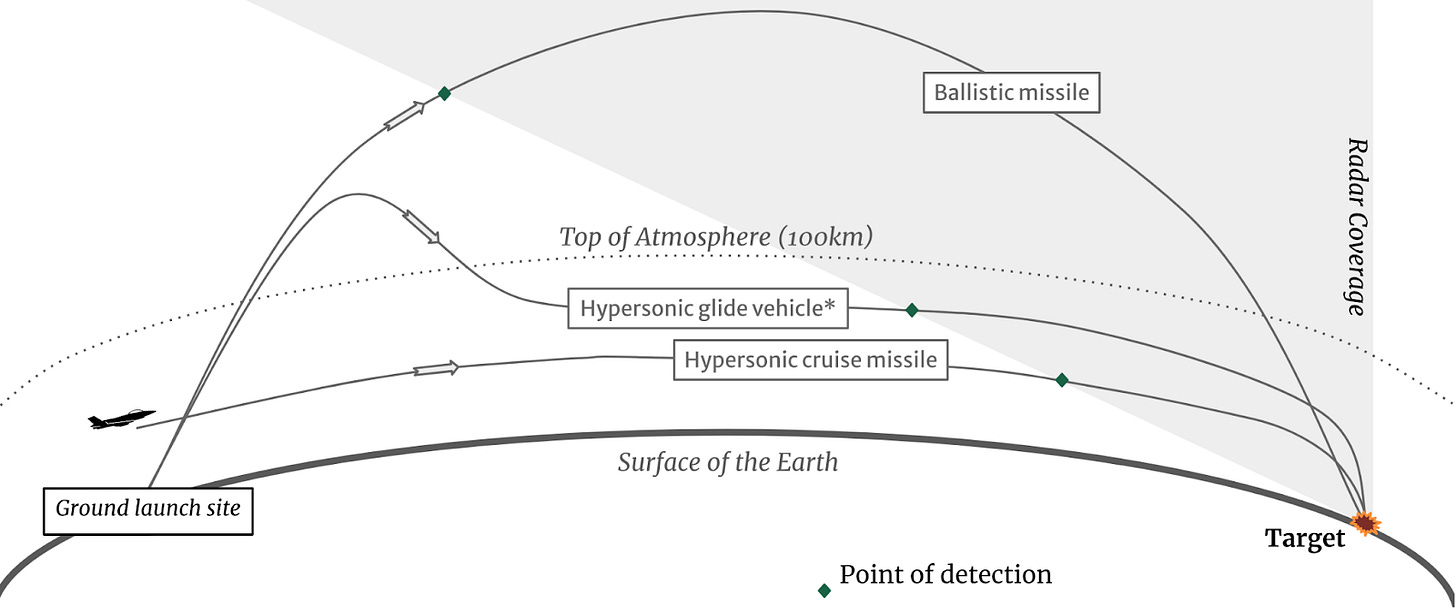

For decades, one of the largest threats facing the homeland has been missiles, given their incredible range, speed, and ability to carry powerful (possibly nuclear) warheads. But today, there are a variety of missiles ranging in trajectory, speed and capabilities, and each demands unique forms of defense.

Ballistic missiles typically follow steady high-arc trajectories often out of the earth’s atmosphere with reentry near targets. Cruise missiles (including hypersonic) meanwhile are powered throughout their journey, providing more advanced maneuverability and a more direct trajectory.

In order to provide a comprehensive defense solution, a nation must be able to first detect, and then prevent the threat – and each threat requires its unique defensive capabilities.

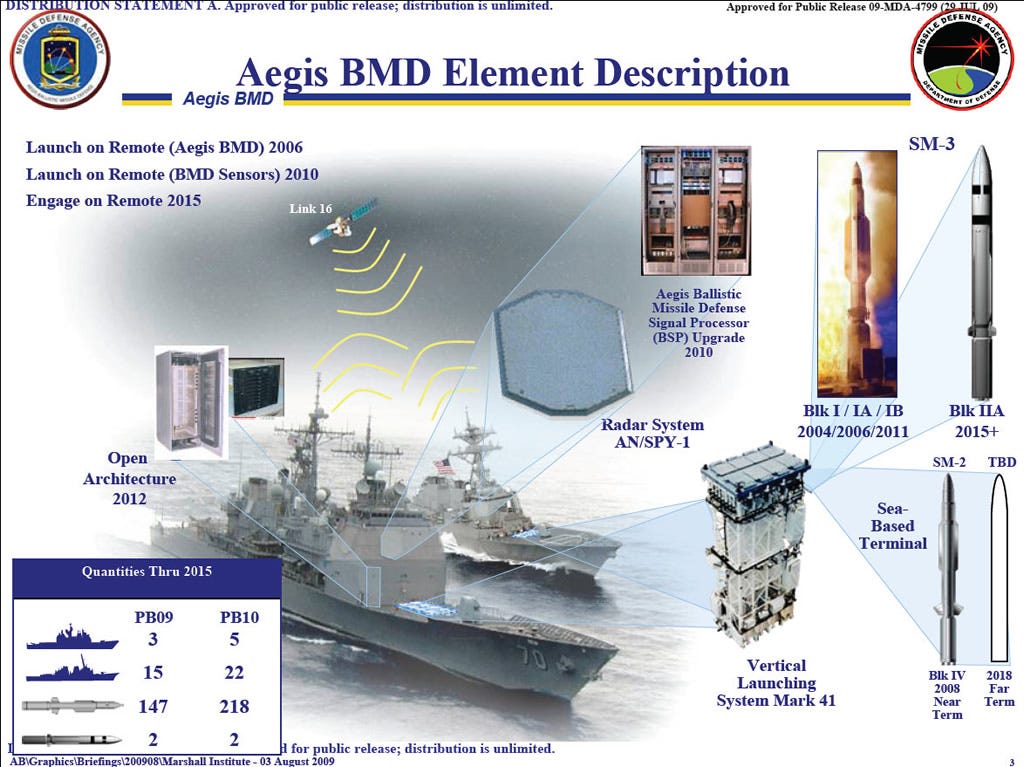

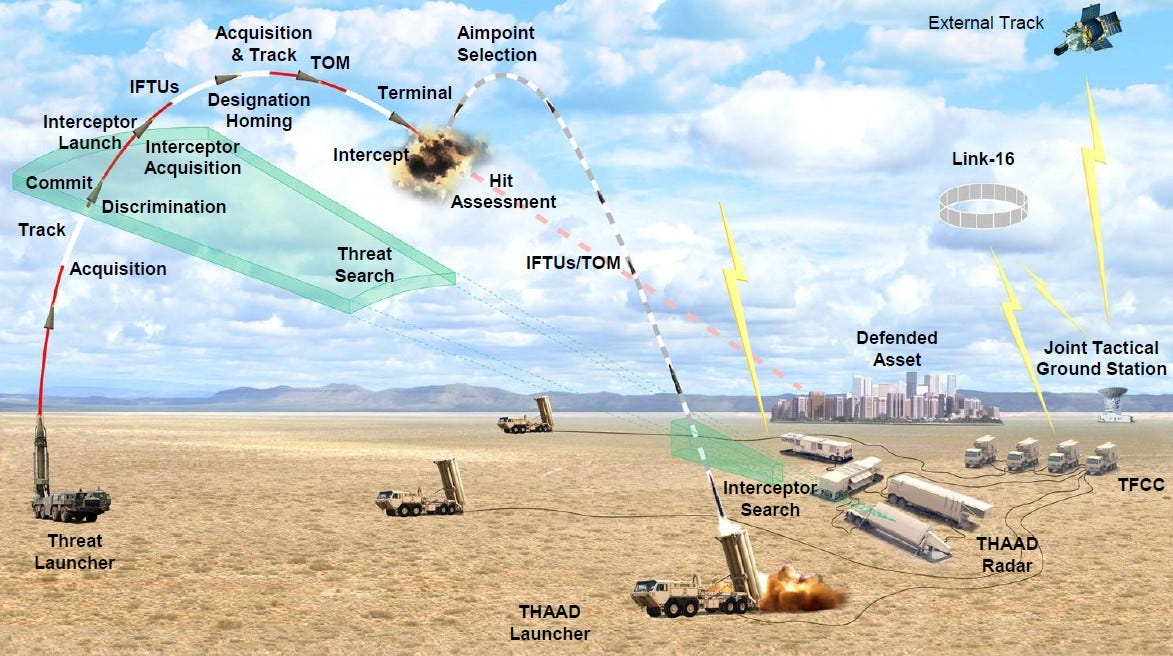

Most of the US missile defense system has been focused on the longest standing threat – ballistic missiles – with elements aimed at each stage of the missile's trajectory; boost (AEGIS), midcourse (GMD), and terminal (THAAD, PAC).

The AEGIS system, for which Lockheed Martin (LMT) serves as the prime contractor, is a naval based system which seeks to intercept missiles in their boost phase, and naturally can be repositioned around the world towards the most salient threats. Under the fiscal 2025 budget submission, by the end of the fiscal year, there are scheduled to be 56 Aegis BMD ships. That number will grow to 69 by the end of fiscal year 2030.

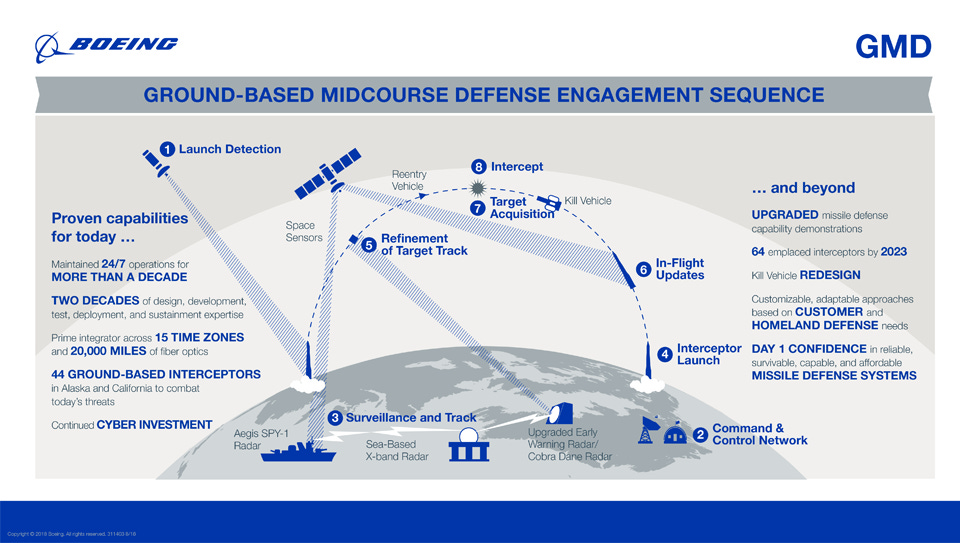

The ground-based midcourse defense engagement sequence (GMD), with Boeing (BA) as the prime, relies on satellite based sensors to detect ballistic missiles in their launch phase, and fires intercepting rockets from fixed missile silos. Currently, the US employs 40 GMD interceptors at Fort Greely, Alaska, and four at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

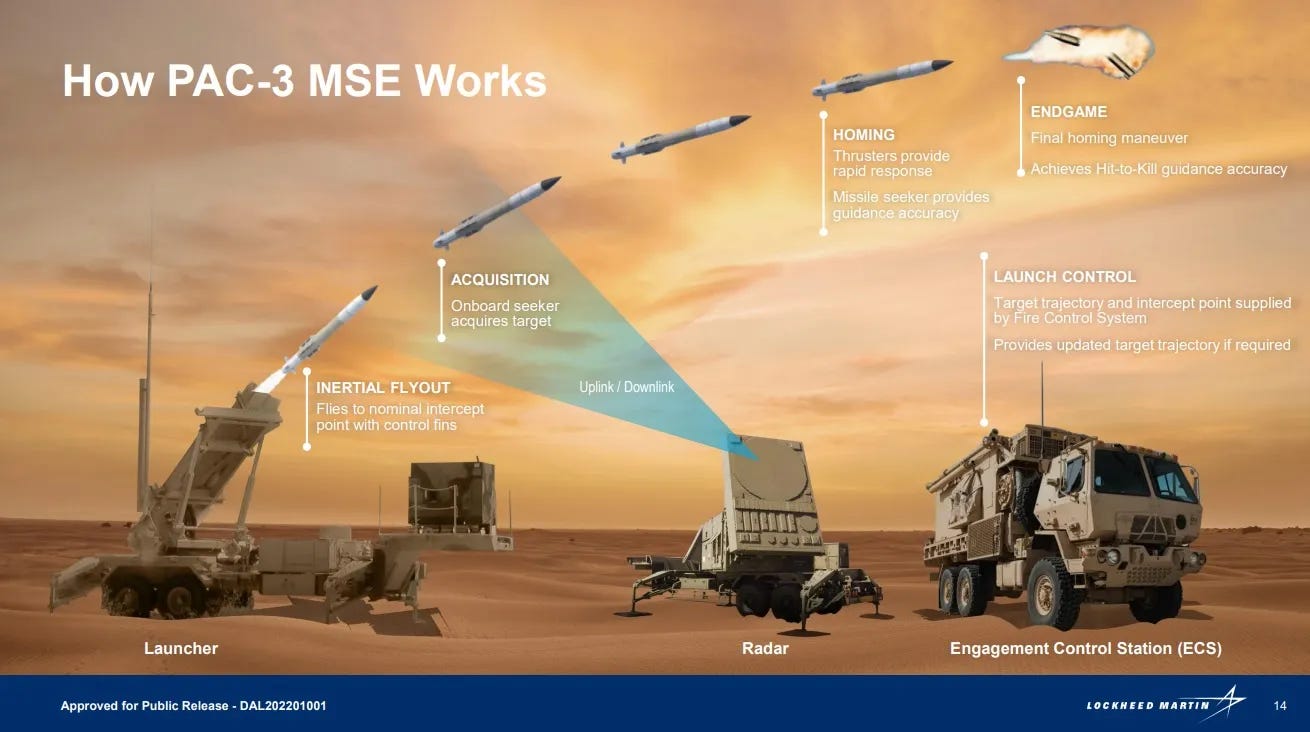

Finally, the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) and Patriot Advanced Capability (PAC) – both systems contracted by Lockheed – are designed to intercept medium to short range ballistic missiles in their terminal phase from a truck-mounted launcher. The system uses interceptors built by RTX (RTX) or L3Harris (LHX).

PAC: (LMT)

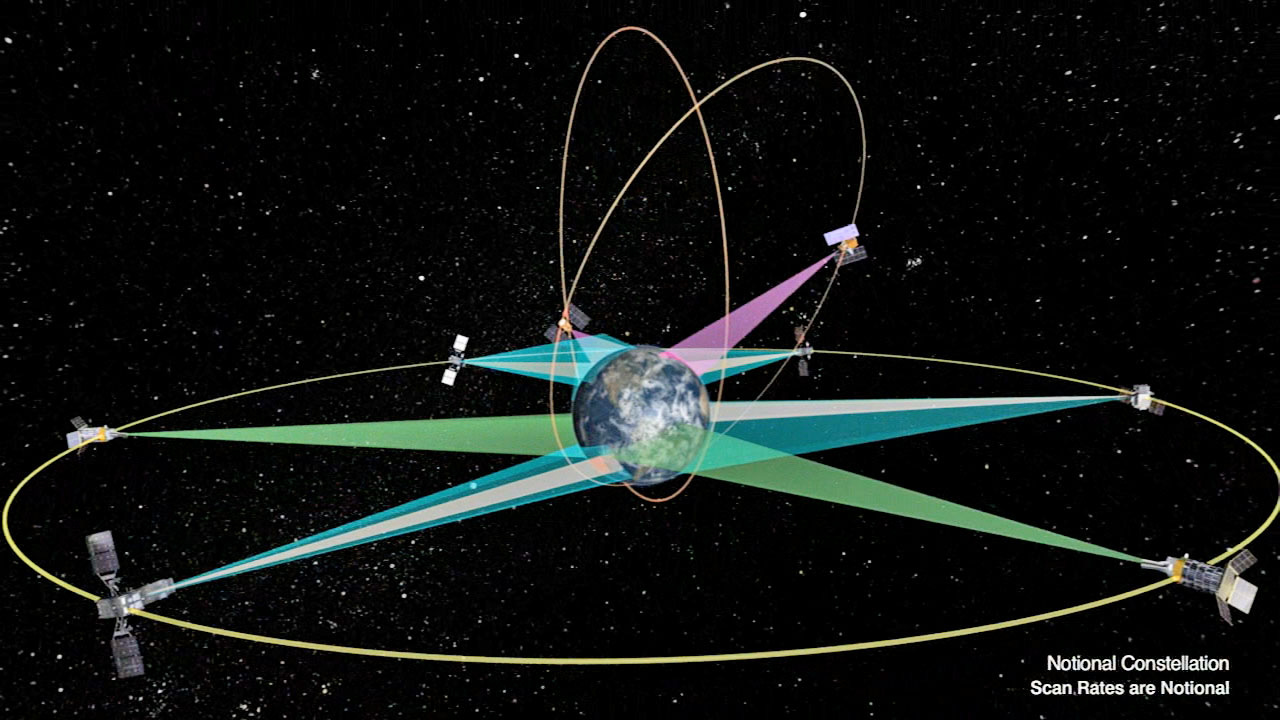

These four layers of kinetic defense however rely on detection and missile tracking from satellites including the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS) and other orbital tracing systems that use various orbital assets (geostationary, highly elliptical, and low earth orbit constellations) to constantly monitor threats, and activate countermeasures through a global command and control (C2) system.

This space layer is at the center of current budget priorities, with three new systems under development:

Hypersonic & Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS) which launched its initial satellites into low earth orbit in early 2024

The Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA) – a low-earth constellation that is slated to receive nearly $9 billion in incremental funding over the next four years

Resilient Missile Warning Missile Tracking – an middle-earth-orbit satellite program slated to receive $5 billion incremental funding over the next several years.

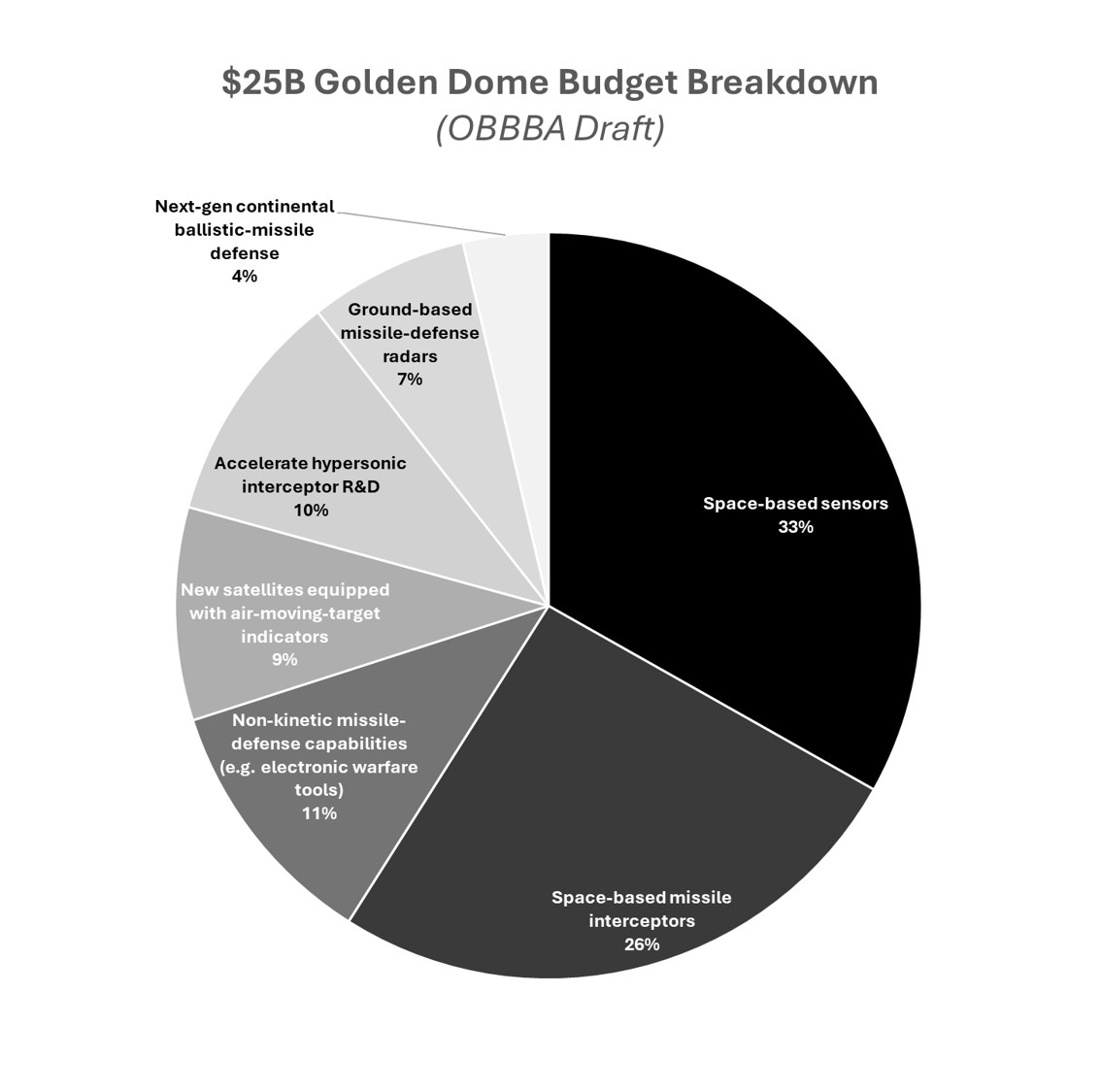

So how does the Golden Dome fit into all of this? The Golden Dome isn’t really a thing, but rather a catchall phrase for budget allocation across all of these various layers.

After Trump signed an executive order titled “The Iron Dome for America” on January 27, 2025, the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) introduced the Increasing Response Options and Deterrence of Missile Engagements (IRON DOME) Act in February, providing significant new funding for these core legacy programs, including:

$12 billion to expand GMD systems, $1.4 billion for the THAAD systems, $1.5 billion for PAC-2 and PAC-3 munitions and MM-104 Patriot batteries, and $1 billion to build Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense infrastructure in Alaska and on the East Coast. Lockheed Martin and Raytheon are the contractors involved.

However, the OBBBA budget demonstrates that the vast majority of new spending will be on orbital and hypersonic technology – including space-based sensors and interceptors.

This budget shows what military strategists have been saying for years – space is truly the next battlefield. And space-based warfare can come in many forms, ranging from sensing and detection, to interception, to satellite-on-satellite kinetic and electronic disruption. The push for greater satellite assets will further boost demand for sectors already benefitting from the commercial space economy – launch services, satellite components, coatings, and communications. Designing and engineering these systems will require the likes of Leidos (LDOS) and Parsons (PSN).

With respect to hypersonic defense, in 2024 the Pentagon selected Northrop Grumman (NOC) as the prime contractor for a Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI), though such a system is unlikely to be field-ready in this decade. Other subcontractors like Kratos Defense (KTOS) are heavily involved in hypersonic development.

Drones and Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems (C-UAS)

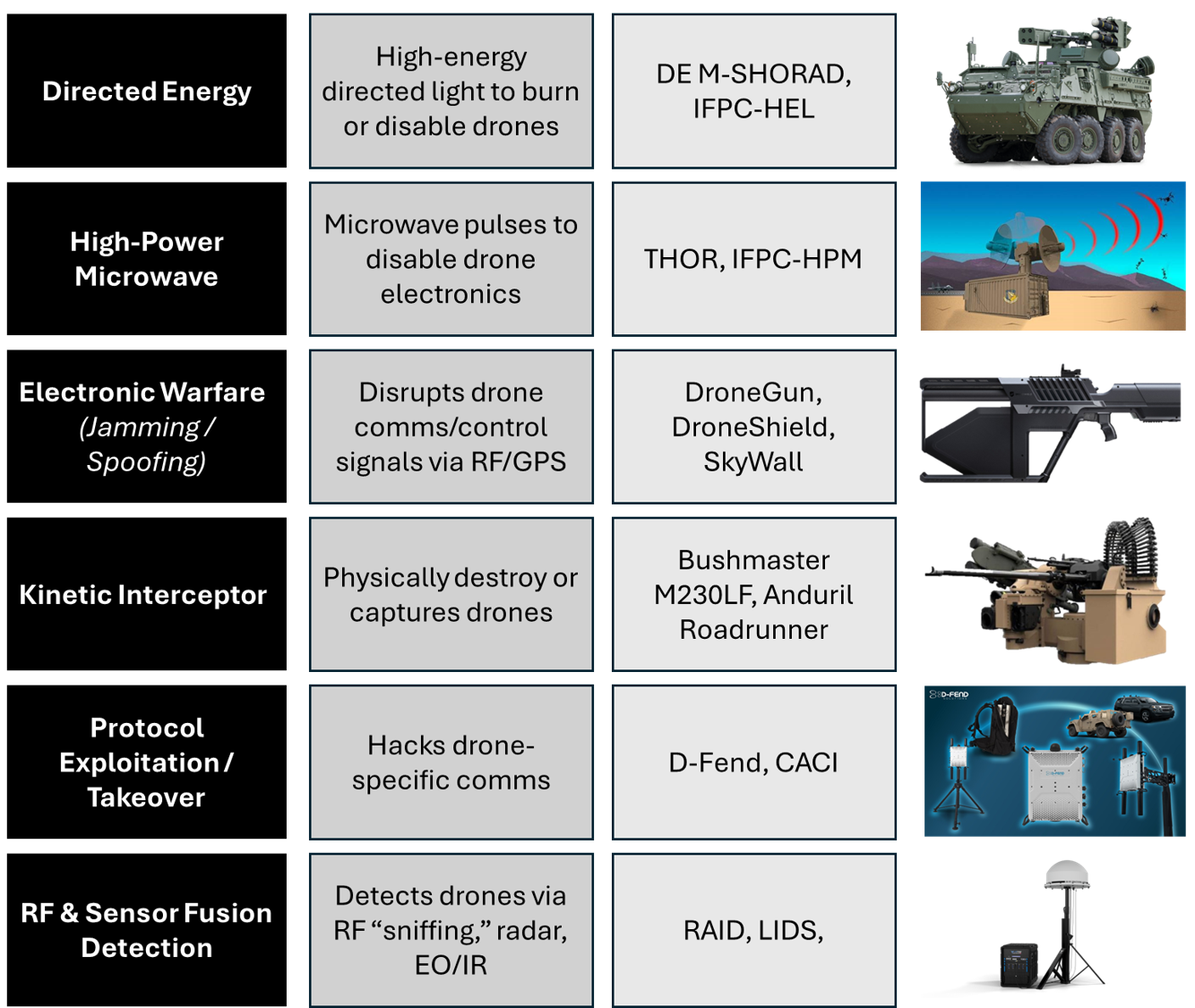

C-UAS: Playing defense against drone threats is a multistage process – first finding, then finishing. Radiofrequency (RF), radar, and electro-optical / infrared (EO/IR) sensors are deployed around critical assets and key hotspots to identify and track enemy drones. After threats are identified, there are a range of alternatives to eliminate the threat, tailored to the circumstances.

Kinetic responses – counter-drone attacks, guided interceptors, or ground based guns – are highly effective when they make contact, but may be less scalable and prone to collateral damage. More precise interceptors may also be significantly more costly than their targets. Kinetic options are most suitable when a confirmed threat is closing in fast and must be eliminated immediately. But in many cases, non-kinetic responses can be more effective, cheaper, scalable and without collateral damage.

Directed energy weapons (DEW) or high-power microwaves can function as “electric guns” downing drones through heat or electronic disruption, with the benefit of low cost and no “hard” ammunition limit (subject to heat dissipation and power source). Systems like the direct energy maneuverable short-range air defense (DE M-SHORAD) assembled by Leonardo (LDO) are specifically designed for counter-UAS activity. However DEWs and microwaves can be impacted by range, weather, and also can create collateral damage including electronics in the area.

Alternatively, drones can be rendered ineffective through disrupting their communications and navigation. Jamming and spoofing GPS positioning systems or interrupting their communication channels ensure drones miss their intended targets. Handheld weapons like DroneShield’s (DRO AU) DroneGun Mk4 delivers advanced counter-drone capabilities in a lightweight, highly portable design, neutralizing unauthorized drones with precision while ensuring minimal disruptions to surrounding environments. Other protocol exploitation techniques effectively “grab the wheel” by overriding communication channels.

Recognizing the immediate need to bolster its low-collateral defense capability the Pentagon launched its Replicator 2.0 solicitation program which seeks to leverage low-cost commercial solutions from non-traditional defense contractors. This suggests that smaller and speculative players like Ondas (ONDS), Unusual Machines (UMAC US), and Redcat (RCAT US), might continue to see a piece of the action.

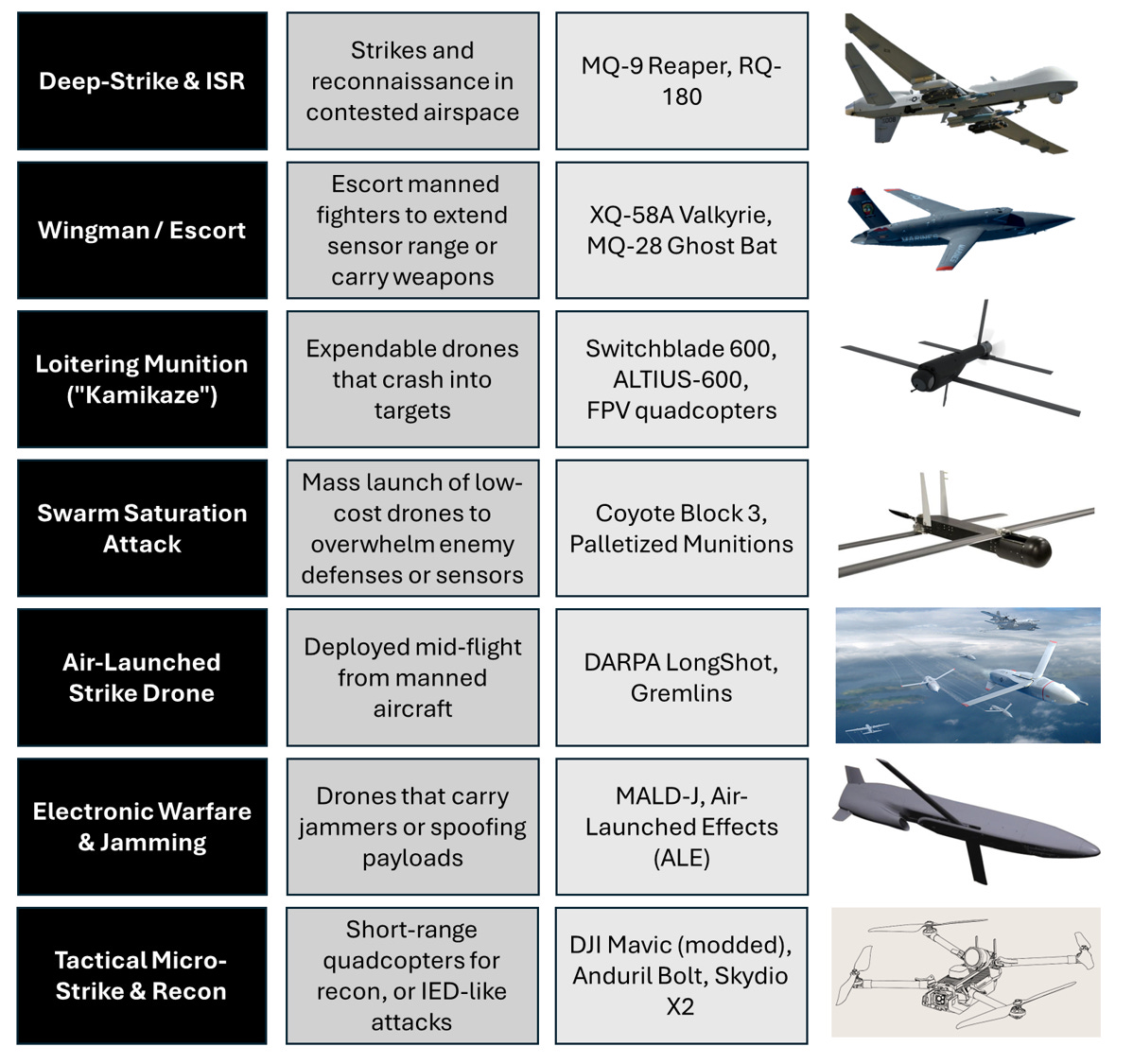

On the offensive side, we should emphasize that the large majority of drones are fixed-wing long-range drones, not the FPV quadcopters that often come to mind. Nevertheless, some of the longest-standing, large, and expensive models like the Reaper (General Atomics) may cede some ground to cheaper loitering munitions, like the Switchblade produced by AeroVironment (AVAV US).

Electronic Warfare

War today begins in the spectrum.

Electronic Warfare (EW) shapes the battlefield by jamming, deceiving, and disabling enemy systems without a single explosion. Enemy forces battle to control signals, sensors, and communications from before troops even hit the ground until the conflict concludes. Failure to control the spectrum can have disastrous consequences.

In last month’s spat between India and Pakistan, Pakistan shot down multiple French-made Rafale fighter jets using its Chinese-developed Chengdu J10s. American intelligence suggested that Thales-developed SPECTRA system failed to detect or jam a PL-15E air-to-air missile fired by a Pakistani J-10C using the KLJ-10A AESA radar. The incident prompted lawmakers to call for an overhaul for the platform’s Spectra electronic warfare systems.

Meanwhile, in the Persian Gulf, reports of electronic interference with commercial shipping navigation systems have surged since the Israel / Iran conflict began, possibly playing a role in the tanker collision that rattled shipping rates and insurance costs.

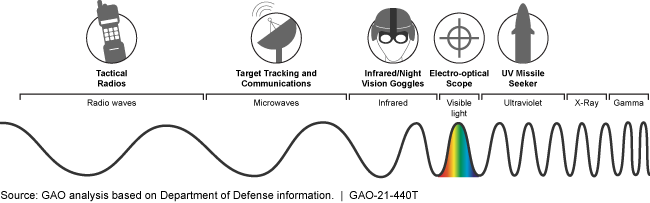

Nearly every aspect of modern warfare rides on waves across the electromagnetic spectrum, ranging from radio to ultraviolet and beyond. Communications, radar, navigation, targeting, and signals intelligence all rely on sending or receiving waves at certain frequencies. Therefore the ability to detect or disrupt these frequencies can paint a vivid picture of enemy assets or render them useless.

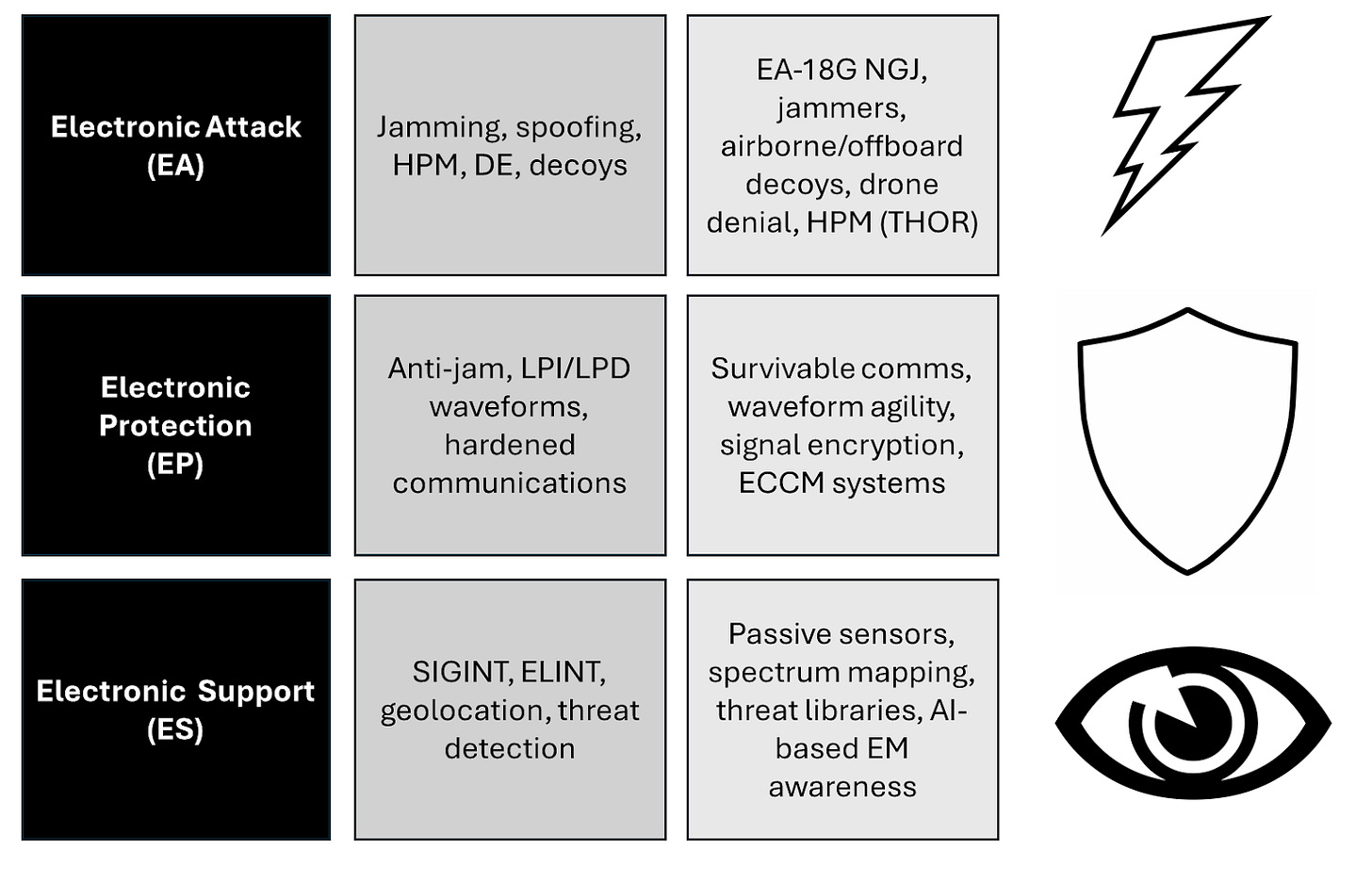

Most official terminology categorizes electronic warfare into three categories; Electronic Attack, Electronic Protection, and Electronic Support.

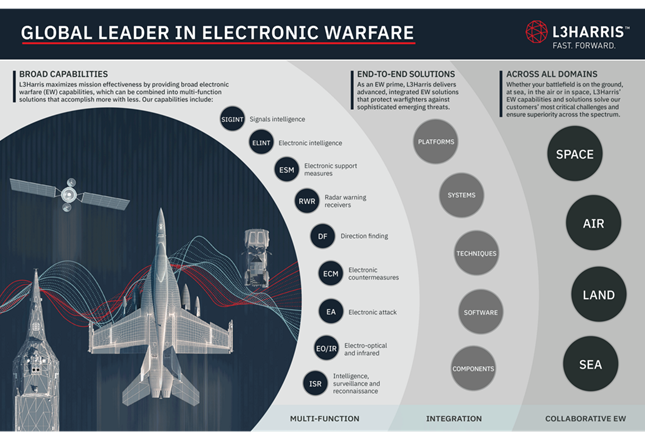

Several major contractors play across all three categories. L3 Harris (LHX US), CACI Inc. (CACI US), Leonardo DRS (DRS US), Mercury Systems (MRCY US) have been long leaders in the EW space, providing a matrix of solutions across both EA/EP/ES and geographic strata (space, air, land, sea).

L3Harris Investor Presentation

Meanwhile, major prime contractor Northrop is advancing its sea-based EW program and the UK’s BAE Systems (BA/ LN) is attempting to add an AI element to advance realtime adaptation with its “Cognitive Electronic Warfare”.

Outside of the traditional leaders, there are plenty of smaller players that have their hand in some section of the applied wavelength science and supply chain, with exposure to defense contracting – companies like Mtron (MPTI) that builds RF oscillators, filters, and resonators necessary for EW.

Modern Surveillance

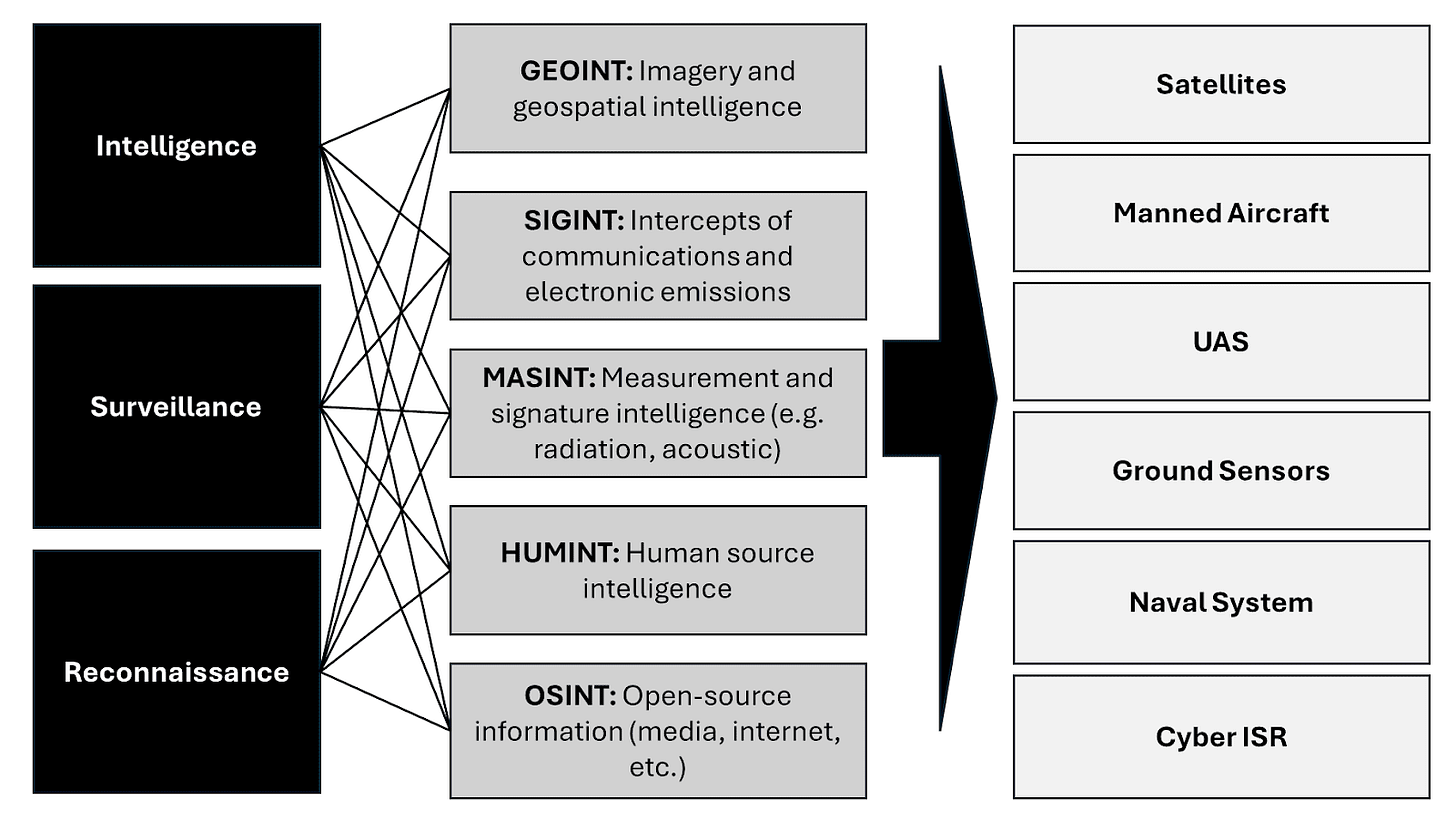

The final pillar of defense is the nervous system of the modern military – intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, or ISR.

The evolving ISR landscape is a natural consequence of the broader technological advancements of our time – big data, space dominance, and artificial intelligence.

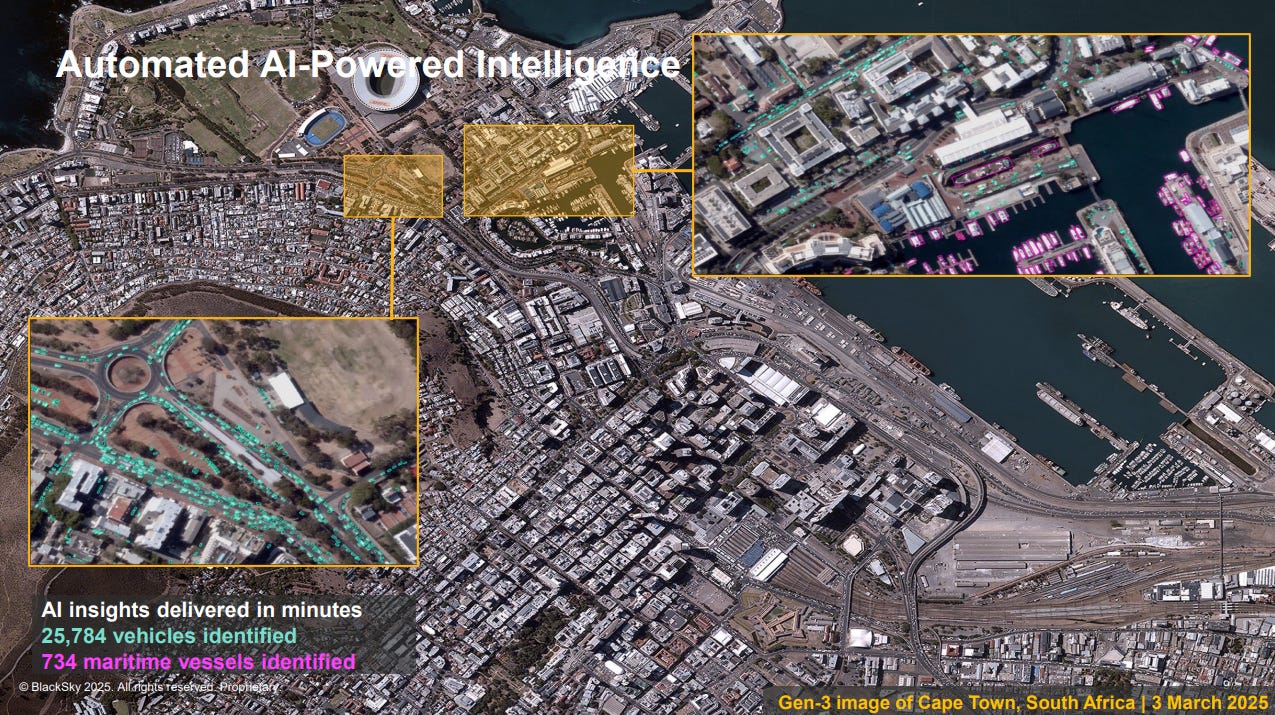

Rather than manually monitoring specific areas of concern, countries can now simply run vast quantities of data – such as massive realtime satellite imagery – through AI/ML systems in order to identify threats that they may not have even known to look for.

In terms of satellite-based visual data, several public companies compete in the defense (and commercial) market – even if the most advanced capabilities are likely completely out of the public domain. In this domain, companies compete on resolution, refresh rate, and range of coverage. The rapidly falling costs of creating LEO constellations are allowing upstarts to compete and win share from legacy geostationary rivals.

For example, BlackSky (BKSY US) provides high-resolution, high-refresh imagery around the world, while using machine learning integration to automatically flag and track objects – ships, tanks, trucks and so on.

Other satellite data providers are either private (Maxar), not defense focused (SPIR/PL), or owned directly by the military and classified.

Another public beneficiary of the trends within ISR is Science Applications International Corp (SAIC US), which builds ground systems, data pipelines, and AI/analytics platforms that turn multi-source sensor feeds into actionable intelligence. While it doesn’t build sensors or platforms, it holds key contracts with the NGA, NRO, Space Force, and Army ISR units to integrate, process, and deliver ISR data across classified operations.

All this sensor data is fed through to what looks like the sickest gaming setup in the world:

Action

Which stocks have upside to drones? Given our confidence in the upcoming wave of spending and geopolitical catalysts, we believe the following companies should be near-term beneficiaries – both in terms of actual spending and market perception. Nevertheless, there is still some uncertainty on the timing and allocations in the final version of the spending, and so we approach with a modest degree of caution, allowing for more aggressive exposure as the legislative hurdle is cleared.