China at the Crossroads

Minsky Moment or Beautiful Deleveraging?

Preface

This is the first of a series called A-Frames, essentially primers on macro situations that cover both bear & bull cases, context, a framework for synthesizing new ideas based on developments and, of course, a list of plays I think are asymmetric.

Here’s a free preview of the first couple pages:

FULL 58 PAGE PDF, 48 FIGURE CHARTBOOK & 4 COMPLETE EQUITY BASKETS / POSITIONING IDEAS BEHIND THE PAYWALL BELOW 👇

A free sample of one of our baskets, our EU/US China Sales Exposure Basket:

3a EU & US Equities: China Sales Exposure Basket (Spreadsheet): Click Here

Please enjoy this free preview of CitriniResearch’s thematic primers. Here are the PDF and the chart book for this article - this is by far the best format for it as this one is quite long:

This is far too long & formatted for Substack - economic data has always been a little boring and I think if you want it to make an impact it needs to be enjoyable to look at so I’m sharing this in PDF format.

Alternative Links (DocSend): Chartbook, Article

For the equity baskets discussed in this article, please view the following spreadsheets.

The first is formatted for the Bloomberg Terminal (as it pulls China Revenue Exposure) - values except for tickers will show up as #NAME if you do not have the terminal, the second is values only with no formatting:

3a EU & US Equities: China Sales Exposure Basket (Spreadsheet): Click Here

If above does not work please copy the link below and paste into your browser:

https://docsend.com/view/mggi4cfx89895rne

If above does not work please copy below and paste into your browser:

https://docsend.com/view/witbpk2ps4paftar

VIEWING THE PDFS IS RECOMMENDED.

However, I’ve put images of the entire PDF below because the clickthrough rate on these PDF links is about 13% (and I hope more than 13% of you are reading what you’re paying for!) but it’s not going to have the proper resolution and there are no hyperlinks etc.

Okay, enjoy!

China at the Crossroads: Minsky Moment or Beautiful Deleveraging?

Objective & Preface:

This article aims to equip investors to evaluate China's economic landscape & its effects on cross-asset international markets, assessing risks and opportunities presented by current challenges. Actionable trading ideas are provided, though China often warrants a nuanced approach. Long-term investors may prefer next week's piece on US fiscal policy.

China will likely pursue reforms, targeted stimulus, and oversight to achieve stable, sustainable growth. Markets may continue to be underwhelmed, as massive stimulus appears counter to China's strategic goals. The focus for investors should be gauging whether potential measures could succeed, not anticipating their timing.

Current conditions make major stimulus probable, but not guaranteed effective. We will explore the context, key indicators to monitor, and trades offering asymmetric risk/reward. While perspectives abound, objective analysis of both bull and bear cases is most valuable for trading China's crossroads. China is, virtually always, a trade – if you’re here for long term investments wait until next week’s article on US Fiscal Primacy.

China's approach to the myriad challenges it currently faces will likely include a mix of structural reforms, targeted stimulus measures, and regulatory oversight, all aimed at achieving a stable and sustainable economic path. All of these measures will likely continue to underwhelm investors – this has been planned for longer than the market realizes, and a “firehose” stimulus would defeat the entire point. The only way the bazooka is coming out is if something goes seriously wrong, which is looking more and more likely, so the best skill an investor can have now is not to be able to anticipate when the stimulus is coming but whether it will work. It’s not guaranteed this time. Let’s explore the basics and then delve a bit deeper into both the background, what to watch going forward to identify opportunities or catalysts, and a few plays that may present asymmetric risk/reward.

Thanks to Steve Hou for translating Chinese language source & Alexander Campbell for his excellent 8 years’ worth of Chinese Property Developer Research.

Figure 2. The 3D's: China's Economic Crossroads

The 3D’s: Deflation, Debt and Demographics

The intersection of these three factors creates a complex and potentially precarious situation. The resolution requires careful policy calibration to navigate the conflicting pressures. For instance, easing monetary policy to combat deflation might exacerbate debt levels, while aggressive deleveraging could depress growth and reinforce deflationary trends

.

Figure 3. China's Slowing Growth Trend

A debt-deflation loop looms, yet China is still a massive economy that has pulled off “economic miracles” in the past.

China's economy took a sharper-than-expected downturn in July, but the “bad news is good news” dynamic often witnessed in Developed Markets has yet to emerge due to doubts that the current government of Xi Jinping will decide to engage in sufficiently supportive economic stimulus measures.

The decline encompassed various sectors, with a few bright spots, but the alarming drop in bank lending to its lowest point in 17 years, paired with a negative GDP Deflator, YoY PPI & YoY CPI for the first time in over two decades, are particularly concerning.

In what should be news to no one, the property market, a central pillar of the economy, is showing significant signs of strain. Declines in sales, increased financial strain among developers, and a notable reduction in new projects signal broader economic distress. These issues could further intensify deflationary trends and disrupt local government funding. While declines in sales don’t seem all that horrible, consider that they threaten to evolve into an increase in fire sales that drives prices down significantly in the frozen market. This already begun in Hong Kong after mogul Eric Chu had to liquidate billions at 40-50% discounts following his wife’s arrest for securities fraud in Vietnam.

China's Demographic Decline

China faces an unprecedented demographic crisis. The first ever population decline last year foreshadows worsening unemployment and social burdens. UN forecasts show China's working population plummeting below 800 million by 2100 - a dramatic shrinkage akin to medieval plagues, inevitably reshaping the socioeconomic landscape.

Figure 4. China's Demographic Decline

China is in a demographic situation that looks set to worsen over the next century and, while it is indeed worse in China than many other countries due to the lasting impact of the One-Child Policy, it is also true that many developed nations are facing similar crises (demographic dividend). The fact is, China may have more levers to pull in combatting this than a country like Japan does.

Recessions are typically not accretive to demographics, an understandable fact considering that people with jobs and good incomes tend to be more willing to have children. While avoiding a severe downturn will not solve China’s demographic issues, it will make them less likely to be resistant to ever being solved by traditional measures – which do exist.

In this area, as a country only decades removed from severe poverty, there are many strides that can be made. Improving healthcare can enable an aging population to remain active, enhancing overall productivity. Childcare support and equal employment opportunities, reforming the hukou system to facilitate greater labor mobility and portable social benefits. While immigration could potentially counter demographic declines, cultural attitudes might limit its effectiveness – something that only gets worse during recessions (think of how significant of a political talking point Mexican immigrants taking jobs was in 2012).

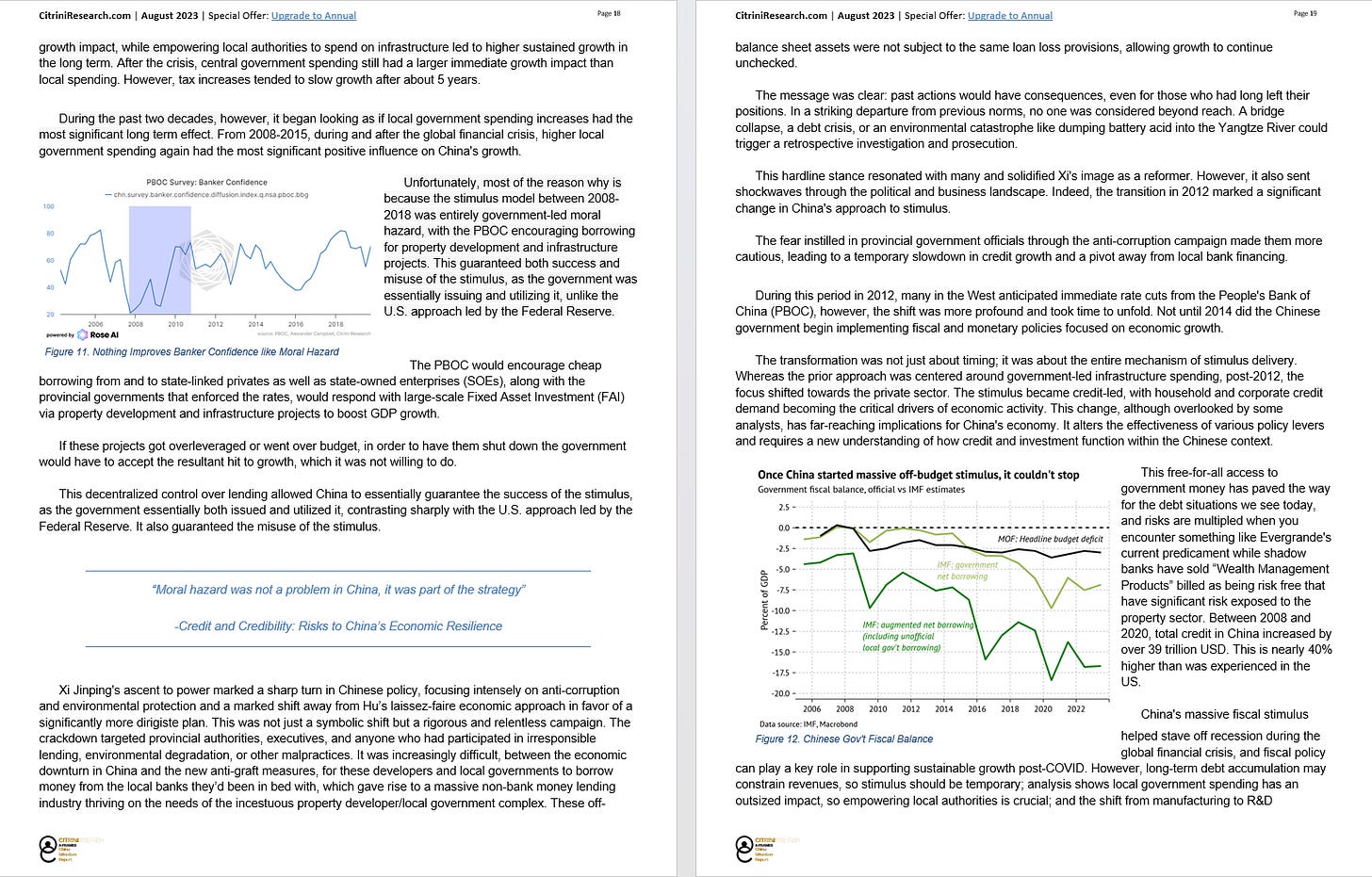

Fiscal Policy: Complacency or Caution?

Equally troubling is China's apparent indifference, with the government's "lying flat" rhetoric symbolizing inaction. This deepens investor distrust and complicates recovery, especially with looming global downturns threatening export demand.

Policy missteps like indications of support followed by underwhelming action undermine confidence further. Expectations shaped by past stimulus have not materialized. The lack of decisiveness amid prevailing uncertainty makes China's economic revival more elusive.

What's more troubling is the Chinese government's apparent complacency towards its economic situation, with policymakers seemingly very firmly positioned behind the curve. The very country which gave us the term "lying flat," coined by the government, has come to approach their economy in a manner that symbolizes this indifference.

Is it a symptom of authoritarian rule, with sycophantic members of the standing committee too afraid to tell Xi things are as bad or worse than they seem?

Is it all going to plan, a masterful attempt as “beautiful deleveraging” that could only have a snowball’s chance in hell in an authoritarian regime?

Is Xi, a strong proponent of “Communism with Chinese Characteristics” just hardheaded or, worse, economically inept?

These are all questions investors in China are likely to ask themselves every day, and while this primer is unlikely to provide a definitive answer, it can help recognize the signs of each.

All these factors are converging to deepen investor distrust in China, further complicating the task of reigniting the market. The lack of a decisive and transparent policy response casts a long shadow, creating an environment where uncertainty prevails, and recovery seems more elusive. This is all complicated by the looming specter of a western economic downturn, which means measures to spur growth in the domestic economy could be thwarted by weakening demand for China’s exports.

Indications of support followed by underwhelming actions have muddled expectations, which are primarily shaped by both the US response to COVID & the previous Chinese response to cyclical downturns like in 2015). China's dramatic pandemic policy reversal shows decisive action is possible but difficult. The PBOC's August meeting emphasized steady, targeted credit expansion, amounting to 16.1 trillion CNY in new loans from January to July. However, the scale achieved so far appears inadequate amid deflation..

Continued lack of clarity and follow through by Beijing, perhaps due to hesitancy over misallocation, has heightened investor caution in a manner that is unlikely to soon subside. China is not the expert game theorist that Japan is, historically speaking, making it unlikely that many games will be played. There will, of course, be “press tests” and “leaks”, but if the PBOC’s decision to cut the 5 Year Loan Primary Rate by 10bps (less than market expectations) and leave the 1 Year Loan Primary Rate unchanged and then come out 3 days later with a press test about cutting 1yr LPR as well because the effect on the yield curve could result in tightening Net Interest Margins, well…that’s not exactly four dimensional chess.

The Last 90 Days of Chinese Policy Promises & Proposals:

Navigating these constraints requires care to avoid unrest. However, excessive caution also risks social instability. Comparisons to the zero-COVID reversal are apt - bold action elicits backlash but inaction brings its own perils. Overcoming hesitancy is key to restoring confidence, despite risks. In attempting to understand the seeming unwillingness to address these issues.

Potential Reasons for Underwhelming Policy Response:

· Lack of Clarity: The transition from broad statements to actionable policies requires a clear and coherent plan. The ambiguity around how to balance competing priorities might create confusion among officials tasked with implementation.

· Fear of Unintended Consequences: Just like relaxing Covid controls, attempting to boosting the economy comes with inherent risks. The fear of (re-)igniting a property bubble may make officials

· hesitant. A similar dynamic was observed during the Great Depression of the 1930s, which ended poorly, as well as with key moments in 2008 (when the US government “allowed” Lehman to fail, for example).

· Bureaucratic Inertia: In a top-down system like China, directives from the top must navigate through various layers of government, often slowing the process. Officials may wait for clearer signals or guidance from higher levels before taking bold action. There may exist reluctancy to take blame, or report negative developments to higher ups, making it difficult for officials to have a comprehensive top-down view.

· Public Perception and Social Stability: Rapid changes in policy, particularly in sensitive areas like property and public health, must be managed with care to avoid social unrest or loss of public trust. However, wait too long to act and the people will break the social contract (as we saw during the protests of 2022).

· Economic Considerations: The complexity of the property market and its intertwined relationship with many aspects of the Chinese economy means that any action is likely to have far-reaching effects. A calculated, deliberate approach might be deemed necessary.

Accountability concerns compound inertia, but deflation risks should outweigh bubble fears. Policies will likely aim to enhance financial resilience while avoiding overstimulation and will likely remain more accepting of moderating economic growth.

Earlier this summer, Xi’s remarks stated of the new economic growth model,

“Most cadres can actively adapt to the new development requirements, but some cadres cannot keep up…Some think that development is about launching projects, doing investments, and expanding scale."

The problem here is the risk of doing too little or sending mixed messages. Instructing these new development requirements, finding out they don’t work and reverting to the old model is likely to be a very difficult approach, especially given how important “Xi Jinping Thought” has become. How long will the Chinese government be willing to implement these new rules during an economic downturn before they become untenable?

Preventing deflation now appears more critical than potential bubbles, if history is any indication. With the economy teetering, bold action may finally align with officials' self-interest, overcoming hesitancy. Targeted stimulus supporting growth, while ensuring affordability and stability, is key to a sustainable revival. Of course, this is a contentious area. Some would say China is still executing its deleveraging, nothing too significant has gone wrong, and others would say it’s already too late.

China has the policy levers available to them to attempt to navigate the current economic challenges. However, the only outcome worse than doing nothing right now is doing something that ends up being ineffective. Once they pivot from half measure to full, there is no turning back. So it’s important to monitor what’s a half measure and what’s not.

The Three Major Adjustments:

The July 24 Politburo meeting marked a notable shift in the verbiage surrounding policy direction, at least.

· Property: By dropping the mantra “housing is for living, not for speculation”, Beijing is signaling a possible easing in property regulations. This could open doors for more speculation and investment but will need to be balanced against long-term sustainability and affordability issues.

· Local Government Debt: The call for “implementing a comprehensive solution” shows an increased focus on preventing a confidence crisis rather than penalizing moral hazard. A managed resolution of debt issues might involve a mix of restructuring, support from central authorities, or other measures to maintain stability in local financial systems. The risks inherent here include SOE consolidation of the property sector or a mishandled systematic risk analysis that leads to unknown unknowns threatening a worsening financial crisis.

· Short-term Stimulus: The pro-growth stance and the mention of an “aggregate monetary policy tool” signaled the potential for rate cuts or other monetary easing. This might be aimed at supporting consumer spending and investment but is more likely to refer to continued cuts to the Loan Primary Rate. This is, perhaps, too little too late. Real rates need to be significantly lower than GDP growth, and it if China continues to experience genuine deflation, then that is likely not currently the case. The average mortgage rate in China was 4.11% in June and is likely to drop to about 4% in July - down ~60bps from this time last year.

Although, as a point of fact, I think it wise to essentially discount the impact of any changes to the LPR. China’s economy has never been extremely responsive to policy rate, with more significant influence from window guidance and fiscal policy. This quote from Zhu Ronji to Alan Greenspan in 1994 illustrates the fact:

“You have increased [interest] rates by 0.25 percent each time and this was extremely effective, but in China the effect wouldn’t be very great. In China perhaps even a 10 percent increase might not have a great effect because some enterprises have no intention of repaying the money and don’t care what the interest rate is.”

However, the Chinese economy has changed significantly from 1994 and the recent policy rate cuts reflect a Beijing that is at least aware their priority must be on stimulating credit, or at least that seems to be the message they wish to send at the current moment.

To Summarize: China following Japan's Footsteps; Lost Decades and Debt Deflation ahead

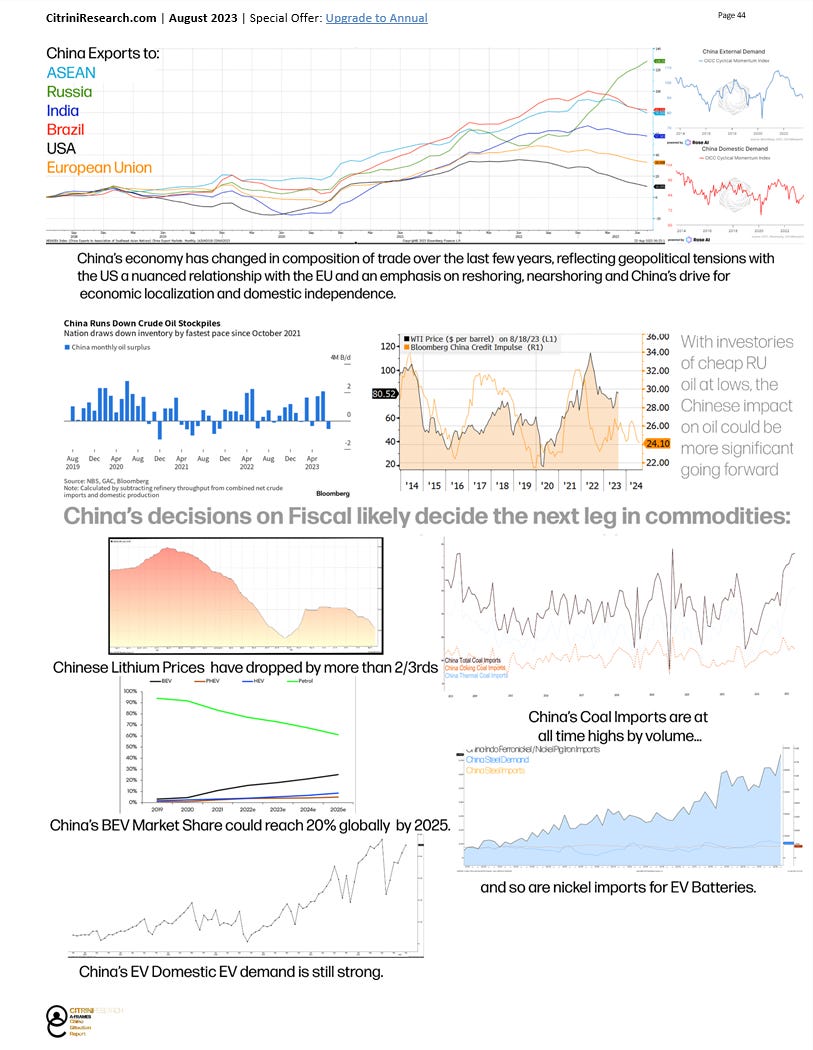

The reasons to be bearish on the Chinese economy are almost too numerous to count, including the sustained leveraging by state-linked corporations, despite private enterprises' deleveraging; systemic assumptions of government backing leading to potential hidden liabilities; the triple threat of debt, demographics, and deflation; restrictions causing reduced access to lucrative Western markets; local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) generating low returns on long-term projects; shadow banking fallout ripple effects, massive first-half losses at SOEs imperiling housing market support, yuan weakness stressing PBOC reserves. and growing concerns over economic outlook.

Recent measures to permit provincial governments to raise funds to repay off-balance-sheet debt and “extend and pretend” measures further reflect underlying vulnerabilities. These factors collectively contribute to a cautious or pessimistic view of China's economic prospects in the near to medium term.

But, even if the economy is more difficult to stimulate, it’s likely even the most fervent bears would cover their shorts if China embarks on an honest-to-god fiscal stimulus campaign. So the real crux of the bear case is essentially the absence of major stimulus like a "capex bazooka". The most salient point of the “Stimulus, Deferred” argument is that China is not in a position to do any sort of significant stimulus, or, that if it is, it won’t.

One argument here is perhaps that Xi's economic priorities seem to most closely resemble those of Andrew Mellon during the Depression - Mellon was obsessed with deleveraging the US economy and refused to extend credit or cut rates, in fact hiked rates out of a desire to balance the budget at all costs even if it bankrupted entire industries

.

“Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate.” -Andrew Mellon to Herbert Hoover during the Depression

Sputtering moves like inadequate LPR cuts undershooting expectations seem to validate this view.

Words are cheap. While strong rhetoric and promises have emerged, markets await comprehensive stimulus plans beyond piecemeal actions that have consistently failed to materialize. Unless convincing solutions are implemented, faith in authorities' ability to stave off a "lost decade" scenario will continue to wane.

As kind of accompanying piece, next week I’ll be releasing the Thematic Analysis on US Fiscal Primacy. So this week you get “what happens when fiscal goes wrong” and then next week "when it goes right and (hopefully) continues to do so”.

My overall *personal* conclusion is as follows (please read the article and develop your own though, please - it’s the entire point of why I presented both sides).

There’s a lot of great risk vs reward asymmetry in longs out 3-6mo or so for Chinese equities. The answer to the title of the post is that there will be no Minsky Moment, in my opinion. It may look more similar to a beautiful deleveraging but it will entail less actual deleveraging going forward than the market expects. The fiscal response will be the great determinant and hopefully this article allows you to refine your reaction function to fiscal announcements from the Chinese government. Most significant would be, in my opinion, measures focused on social welfare and consumer spending. Eventually the market will get used to a slower growth China, unless there’s a contagion event that’s uncontrollable.

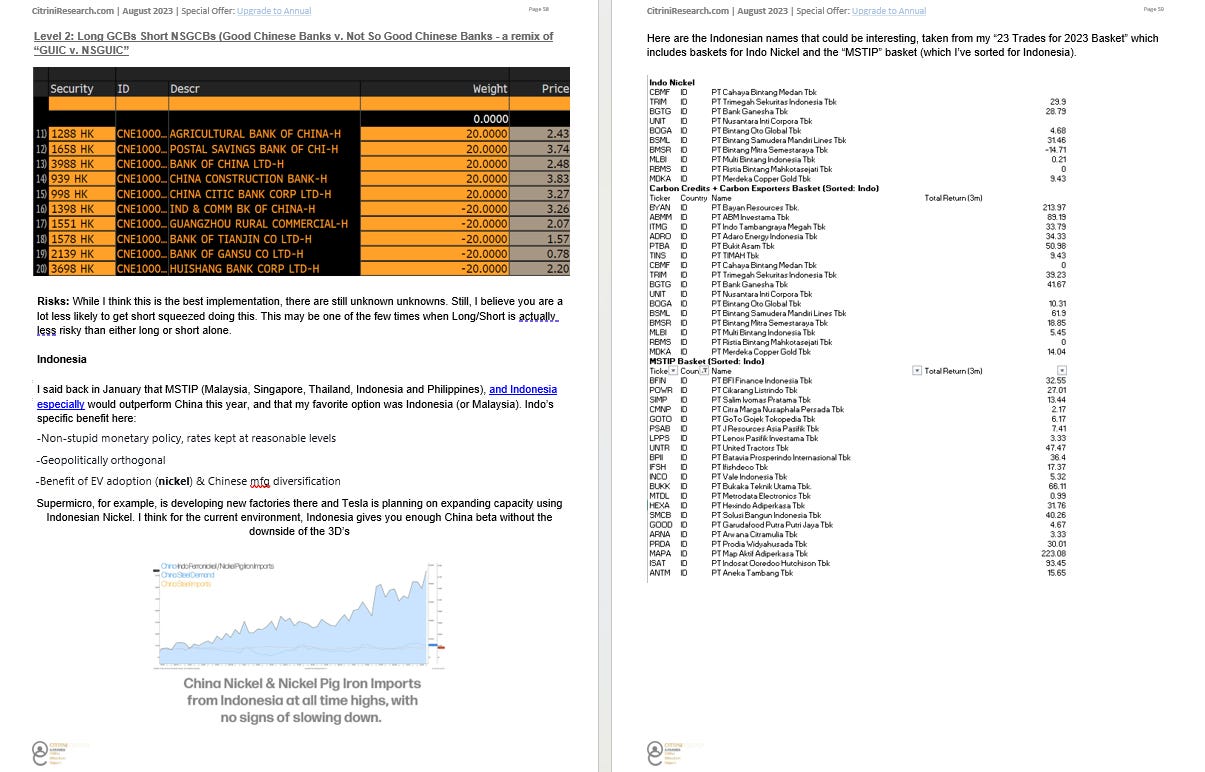

BABA is very cheap still, my favorite of all the ADRs (although it may end up being PDD, it’s path dependent and right now BABA does have more upside I think), and I bet a few of these Chinese financials end up surviving.

The Chinese Yuan (CNY) will likely continue to weaken, as it’s caught in a cycle of no fiscal stimulus = weaker economy = lower rates = higher rate differentials = weaker currency or fiscal stimulus = money printing = weaker currency. That isn’t to say that the PBOC will not fight back, they will at all costs. Well, perhaps *most* costs.

I don’t think China can afford to spend a trillion dollars defending CNY fixing like they did in 2015. This is why I think you can acquire significant asymmetry in Chinese equities and FX hedge it / fund it with a short on CNH (despite it being pretty weak already) and still outperform / benefit from a bit of a hedge. The ratio to which you are short CNH vs. long CN equities depends on how bearish you are overall. This “Chinese Stimulus Barbell” (with CNH as the bar) was described in the article above but really you could do it with anything. Anything you think is ridiculously cheap in China, you can balance it with a short CNH (for the time being). Try to be opportunistic with the entries, however, and take advantage of PBOC/Market back and forth dynamics.

If you are uninterested in doing the basket, you can just buy some of the ADRs or use an ETF. FXI MCHI KWEB etc are all fine of course, and while your risk will be reduced if you implement it in a more diversified, picky manner, if I had to just pick some names that have ADRs, in order of attractiveness:

PDD

BYDDY

HSHCY

BABA

JD

NTES

MPNGY

HTHT

ZTO

YMM

Anyway, there’s a lot more in the article but figured I’d give you the upshot here if you just scrolled past it :). Go read it! I think it’s pretty good. Also, something important here: there are a few Chinese names in the AI basket - if you are running it and planning on putting on our “Chinese Equity Barbell” basket I would exit them so you aren’t doubling up on regional exposure.

Enjoy!

Positioning. I’m playing for a violent, flow driven unwind of existing positioning. That’s not going to be as strong with a first lien bond in this situation imo. But you can do whichever tenor or seniority you want! I didn’t specify in the article, I am just saying I like the 2031

Citrini subs eating good tonight <3