A Tale of Two Tariffs

History Doesn’t Repeat, But it Does Plagiarize

“It is perhaps an erroneous opinion,”

Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1781,

“but I find myself rather inclined to adopt that modern one, which supposes it is best for every country to leave its trade entirely free from all encumbrances. In general I would only observe that commerce, consisting in a mutual exchange of the necessaries and the conveniences of life, the more free and unrestrained it is the more it flourishes, and the happier are all the nations concerned in it. Most of the restraints put upon it in different countries seem to have been the projects of particulars for their private interest, under the pretense of public good.”

In the two weeks since “Liberation Day”, I’ve spent one week in the U.S. and one in China. In both countries, I’ve been speaking with business owners affected by tariffs (in between writing “Insuring Against Insanity”, “Seeing the Stag” and “Talk to me, Goose”).

Importers and exporters alike, businesses in these two very different places dealing with any degree of international trade have one thing in common: uncertainty.

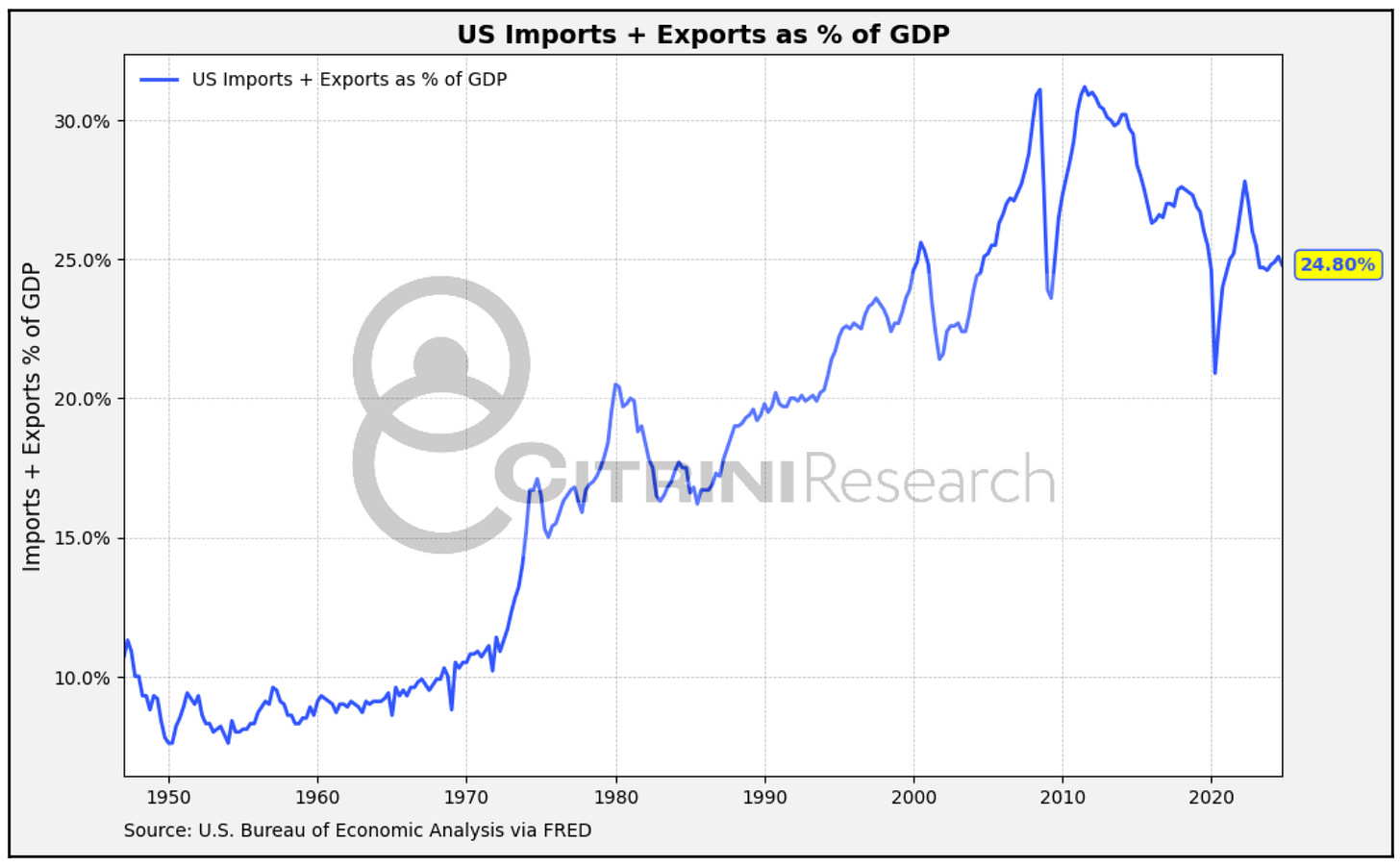

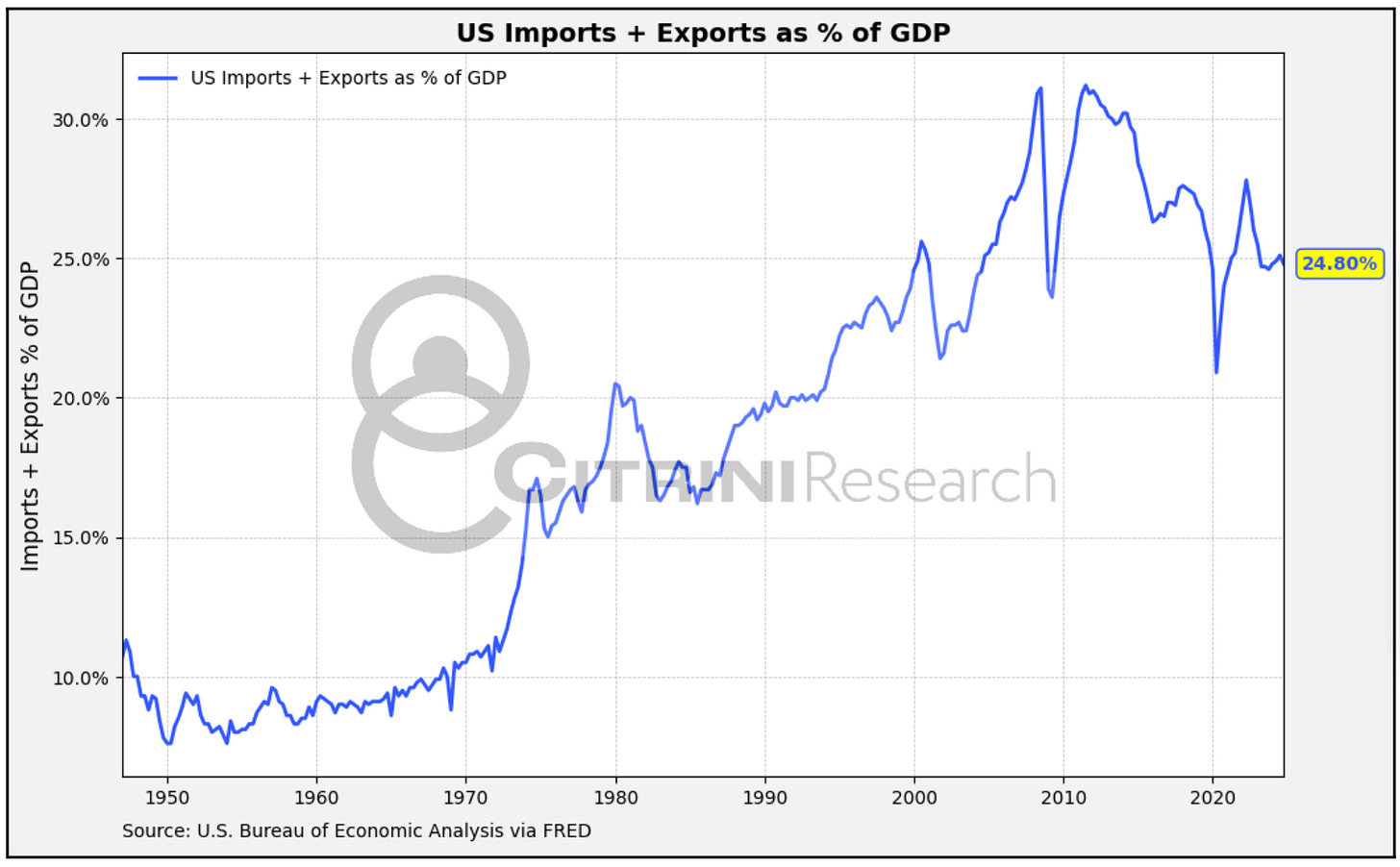

And why wouldn’t they be uncertain? The simple fact of the matter is that nearly everyone alive today has only experienced a world of increasing globalization, relatively free trade and the U.S. as the world’s hegemon and reserve currency.

With that called into question, it’s clear that investors and operators alike are reaching for anything close to a framework for how to proceed. “Wait-and-see” is a deadly proposition for a system built on “just-in-time”, but there’s not much else to do.

For example, speaking with a top 100 (by trade volume) company in Shanghai yielded the following insight, “By now, we’d be ramping up to begin dealing with orders for the holiday season. We have gotten absolutely none of them.” A dual realization should hit anyone reading that who is unfamiliar with the way importing goods works. First, that ordering for an event begins 8 months prior. Second, that it’s a pretty big shift we’re watching unfold.

Chinese companies have broadly viewed duties historically as something they can adapt to. In the past, a 10% tariff might result in the buyer reaching out to the Chinese factory to drop prices (which they’d do with ease). While factories obviously cannot drop prices to account for a >100% tariff, they do believe they can drop prices enough to maintain their post-tariff cost advantage versus US domestic manufacturing. But that doesn’t matter much when nobody is transacting.

It’s been more than two years since I’ve published a history piece to CitriniResearch. After all, our tagline is “you’ll never have to ask ‘what’s the trade?’”, and these pieces are not necessarily actionable. However, the last one I wrote - an examination of how markets have failed to price in geopolitical risks through the lens of WWI (similar to the one we’ve just seen that was…not priced in) - has aged relatively well.

And because the market is primarily going to trade like a tariff rate swap for the foreseeable future, it seems timely. Sometimes, the only shot we have at understanding the future is by understanding the past.

There have been a lot of -isms that have been thrown around without much in the way of care for meaning - mercantilism, isolationism, protectionism. While I am decidedly not an economist, I am an economic history enthusiast. Consider this a bonus article, a very rare instance where I am not talking about which stocks I want to buy or sell, or making directional calls on FX, equities or rates.

Understanding Tariffs Historically

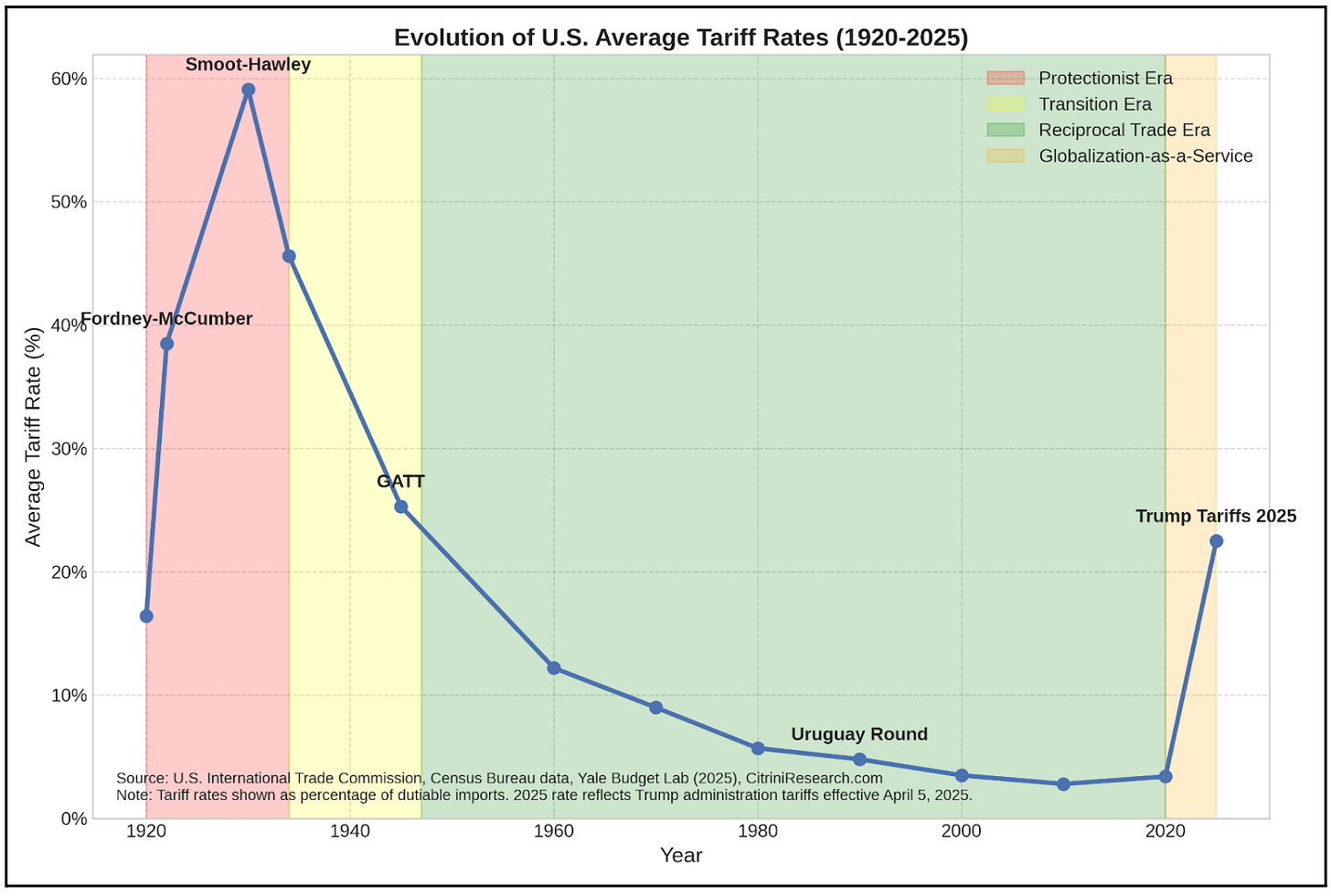

Very few of us alive today have real first-hand experience in what the economy looks like during periods with similar effective tariff rates to today. The best exploration of the history of the tariff in the U.S. that I’ve found for formulating a framework is the book Clashing over Commerce, and I found myself re-reading it over the past couple weeks.

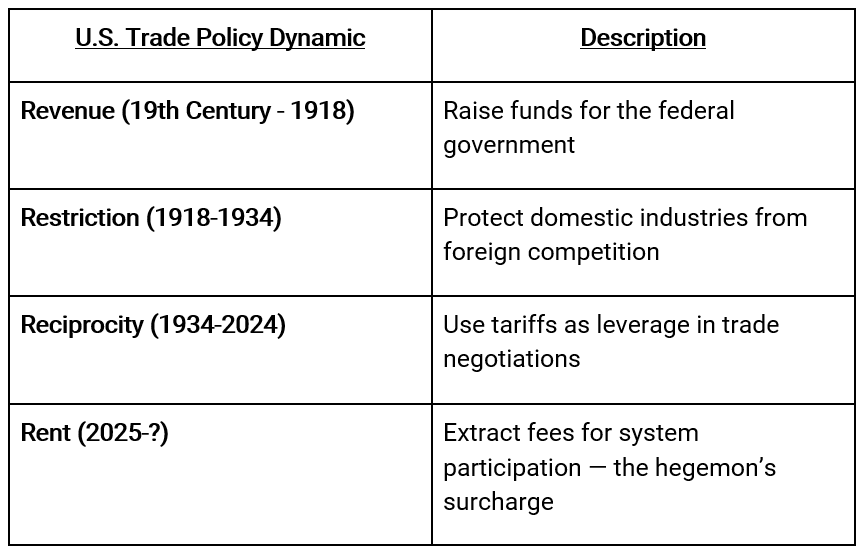

Written by Douglas Irwin, the reigning historian-archaeologist of American trade policy, it lays out the “3 R’s” framework for understanding the political economy of tariffs.

The three R’s of U.S. Tariffs, historically:

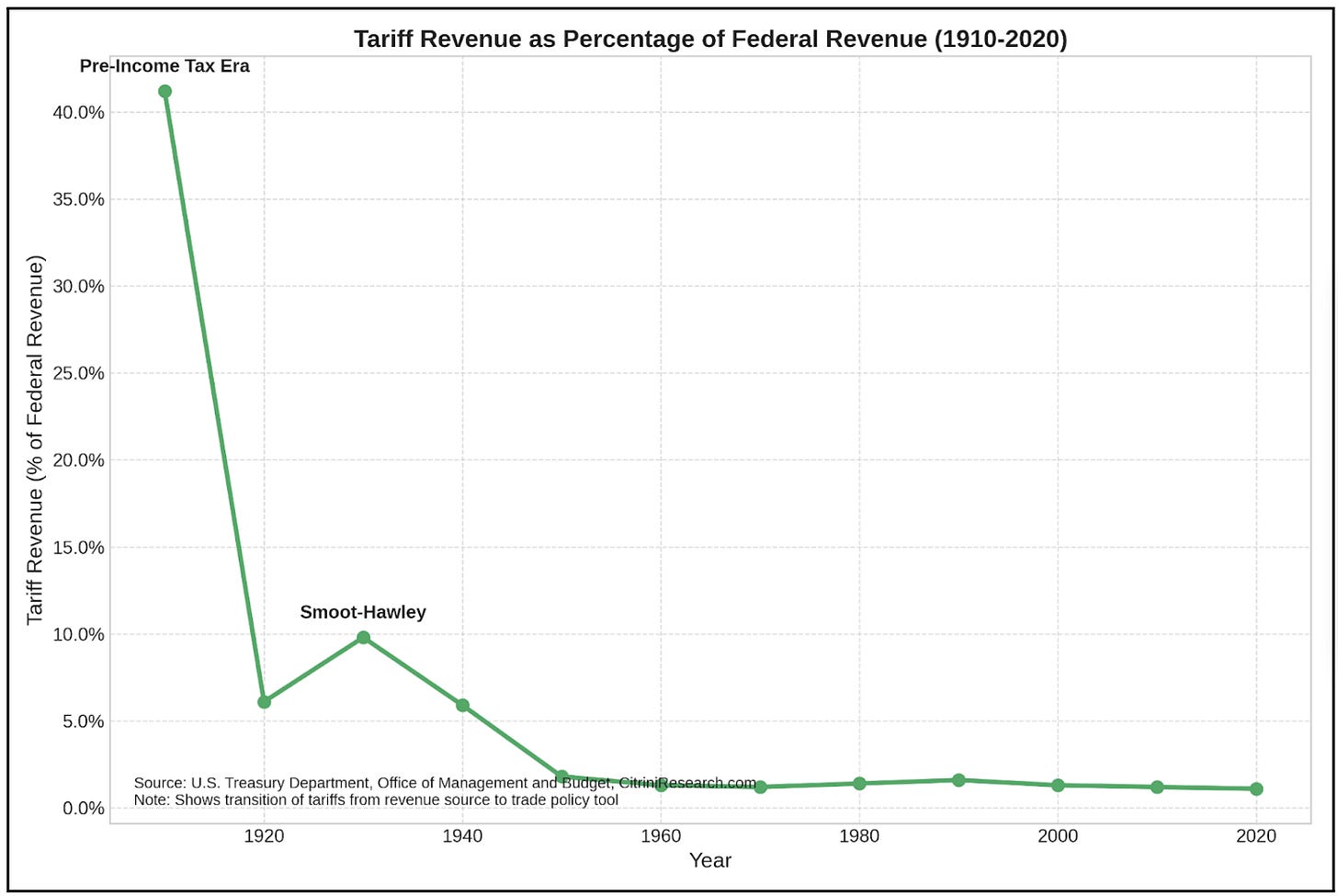

1. Revenue

Tariffs as the primary source of government funding.

This was especially true in the 19th and early 20th century.

Tariff bills have been long criticized for being opaque and unwieldy policy tools, even when they were the primary source of government funding, as this political cartoon from 1883 demonstrates.

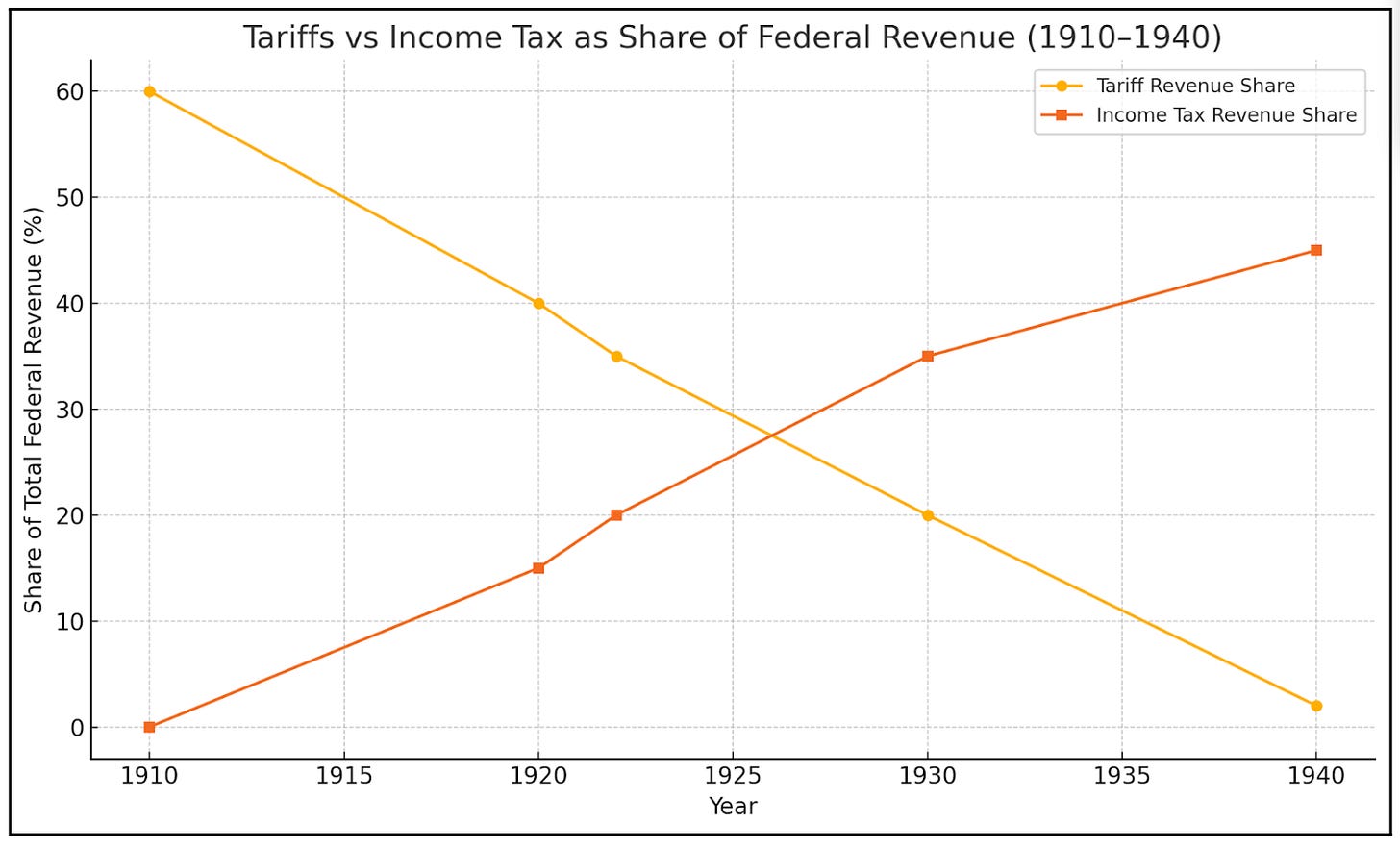

Before the IRS (1913), the U.S. had no income tax. Tariffs accounted for >90% of the government’s revenue in the 1800s. Back then, tariffs were primarily used for revenue rather than protectionism - viewed as a more palatable way to tax the population that wouldn’t lead to a revolt. For the first third of the 20th century, less than 15% of U.S. citizens paid income tax. The rest paid invisibly in the price of imported sugar, lumber, and wool. Tariffs were the original stealth tax: collected at the port, felt at the checkout.

Primarily, they were a way to fund the state without creating internal taxes that might provoke political backlash (a lesson learned from things like the Whiskey Rebellion). In Irwin’s telling, revenue concerns dominated trade policy during the early republic, and even protectionist arguments had to be framed through a revenue-first lens.

2. Restriction

Tariffs as protection for domestic industries.

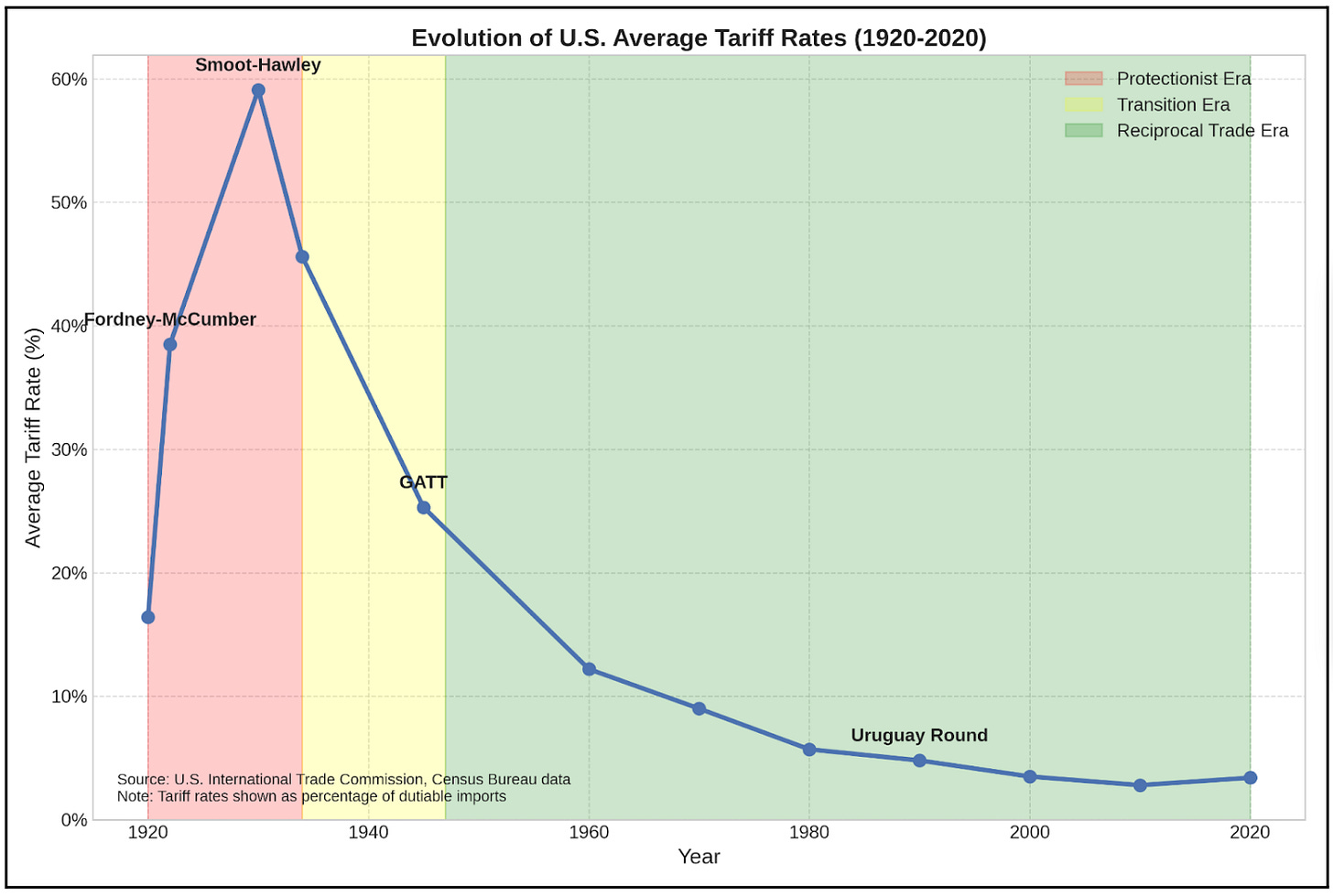

After WWI, tariffs became more of a political tool to pander to domestic industries facing foreign competition - the protectionist dynamic.

Irwin shows that as the revenue motive declined (thanks to the income tax), the restriction motive rose. Post-World War I, tariffs increasingly served industrial lobbies, not the Treasury.

3. Reciprocity

Tariffs as bargaining chips in international trade negotiations.

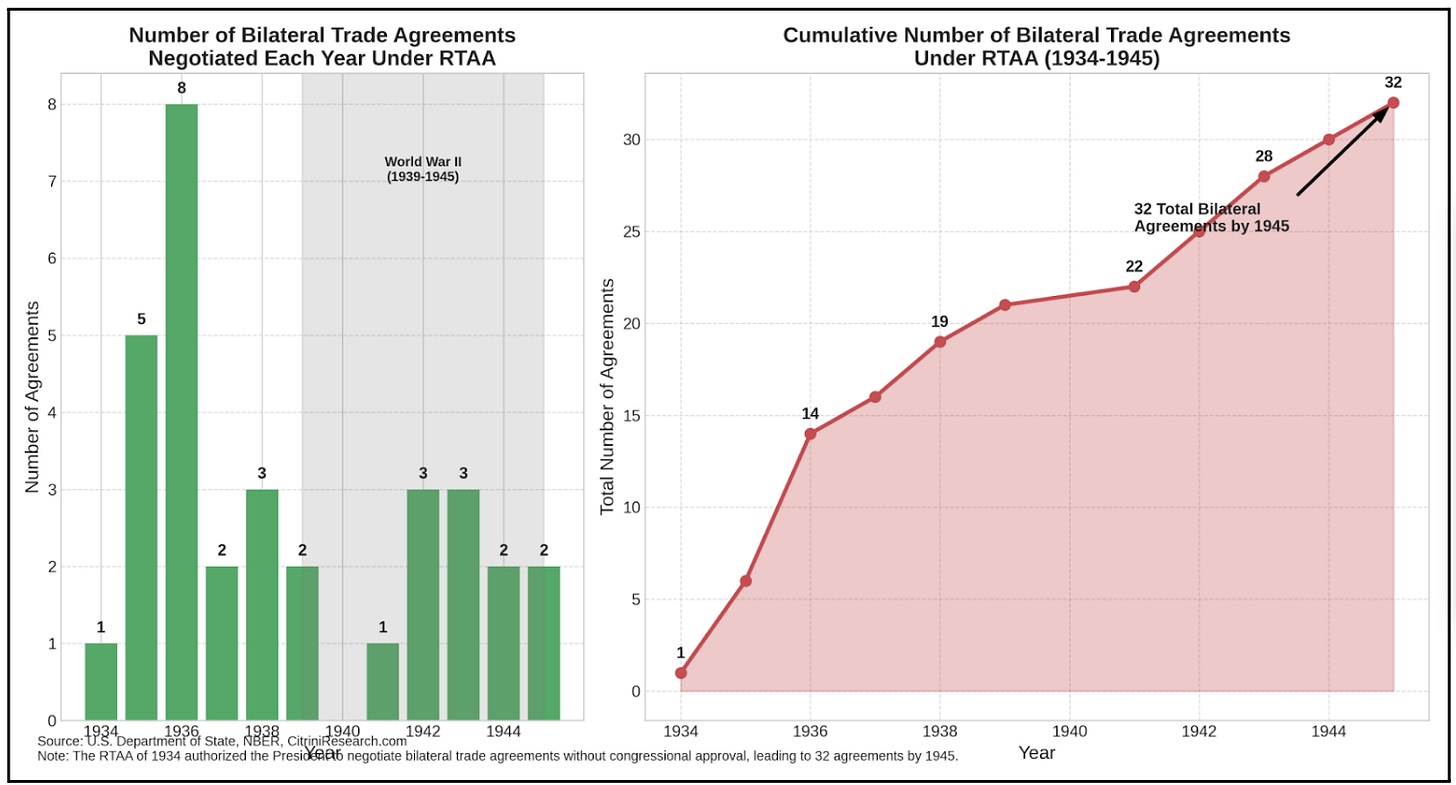

By 1934, income taxes were slowly replacing tariffs as the main source of federal funds — a shift accelerated by New Deal programs and WWII. Tariffs became bargaining chips in global trade negotiations.

This was the logic behind the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (1934), GATT, and later the WTO. The era of Reciprocity marked the post-Smoot shift toward liberalization and away from isolationism. The hegemon (the U.S.) offers tariff reductions in exchange for access to foreign markets. Tariffs became less of a wall and more of a lever. VERs, backroom deals focused on forcing countries to impose export restrictions, took over from tariffs which eventually gave way to more and larger free trade agreements. This fueled the multilateral free-trade era that was emblematic of the late 20th and early 21st century.

1922: The Fordney–McCumber Tariff

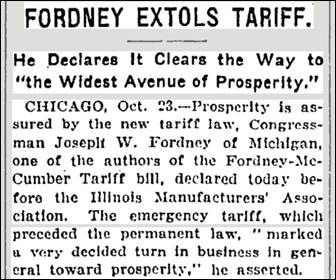

The Fordney-McCumber Tariff was an early prototype of protectionist overengineering and the first real example of tariffs for reasons external to revenue.

Picture Congress in the post-WWI glow: America was flush with industrial output, but farmers were increasingly broke. The core fear of the day was cheap European competition, but Europe still owed us a lot of money and couldn’t sell anything to us (because we kept raising tariffs). So, obviously, we raised them again.

In 1921, Congress passed an Emergency Tariff, followed by the comprehensive Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act of 1922, signed by President Warren Harding.

This law raised tariffs well above the low levels set by the 1913 Underwood Tariff and higher than they’d been since the U.S. Civil War (although on dutiable imports, the rate was roughly where it was back in 1909 under Payne-Aldrich). Furthermore, it gave the President authority to adjust rates by up to 50% to “even out foreign and domestic production costs” .

The result? A booming 1920s for urban industry, a protracted death spiral for agriculture and the slow suffocation of European trade surpluses, which they needed to, you know, pay us back for all the war stuff.

For American industry, the 1920s roared. Manufacturing output increased by nearly 50% between 1922 and 1929. Unemployment dropped from 6.7% in 1922 to 3.2% in 1923. Steel, chemicals, automobiles—all flourished behind the tariff wall. The protected sectors hired, expanded, and profited. Corporate profits nearly doubled during this period.

For agriculture, however, the story unfolded differently. Farm income plummeted from $22 billion in 1919 to $13 billion by 1922. While urban prosperity soared, rural America slid into a depression that predated the Great Depression by a decade. Why? European markets closed in retaliation, and American farmers—who had expanded production during the war—faced collapsing demand and prices.

In the 20s, protectionism delivered concentrated benefit. If you were an urban industrial worker, these were good times. If you were a farmer, this was the beginning of 20 years of misery. The protectionist dynamic had begun, and it had seen some measure of success for some (although at a high cost for others)

1930: The Mistake

A Mass Tariff, A Massive Depression

1928 - Herbert Hoover is riding high. The Great Engineer had just won the presidential election in a historic landslide: 444 electoral votes to Al Smith's 87, carrying more counties than even Warren Harding had in 1920, and securing 58% of the popular vote. The "Prosperity President" had promised Americans in his acceptance speech "a final triumph over poverty" – words that would soon come to haunt him.

The stock market was soaring, unemployment was low, and Americans were buying automobiles, radios, and refrigerators at unprecedented rates. The Fourth Party System, dominated by Republicans since McKinley's victory in 1896, seemed as entrenched as ever.

And just like his Republican predecessors, Hoover was a devotee of the protective tariff. "The Republican Party has for seventy years supported a tariff designed to give adequate protection to American labor, American industry, and the American farm against foreign competition," Hoover declared during his campaign. He made tariff protection, particularly for agriculture, a cornerstone of his economic agenda.

As Secretary of Commerce under both Harding and Coolidge, Hoover had developed a clear protectionist philosophy: America should largely confine its imports to products that couldn't be produced domestically. This wasn't radical – it was the culmination of the McKinley Republican tradition, the natural extension of the Fourth Party System's economic orthodoxy.

Hoover used the “success” of the Fordney-McCumber Act (with total American imports having increased since the passage) as proof that the United States could concurrently protect its own industries AND expand sales in Canada. He wrote in 1926 “In considering the broad future of our trade, we can dismiss the fear that an increased tariff would so diminish our total imports as to destroy the ability of other nations to buy from us”. In a campaign speech in 1928 he stated, “there is no practical force in the contention that we cannot have a protective tariff and a growing foreign trade. We have both today.”

Then came Black Thursday, October 24, 1929. By Black Tuesday, five days later, the market had lost over $30 billion in value – nearly twice what America had spent fighting World War I. The Roaring Twenties screeched to a halt. Amidst the turmoil, tariff talks did not subside but ramped up:

Rather than reconsider the tariff legislation in light of the economic earthquake, Congress doubled down. The initial agricultural tariff bill morphed into what we now know as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, named after its primary sponsors, Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Representative Willis C. Hawley of Oregon. Originally a farmer-first relief bill, it metastasized into a Frankenstein of industrial protectionism.

What had begun as a targeted effort to protect American farmers became a free-for-all of protectionism. As the bill worked its way through Congress throughout 1929 and early 1930, the list of protected industries grew exponentially. The bill eventually included tariff increases on over 20,000 imported goods, creating the highest tariff rates in American history since the 1828 "Tariff of Abominations."

Cartoon shows an exhausted GOP elephant seated in the middle of the road bracing himself against a large stone labeled "Tariff Legislation."

Markets didn’t like it. 1,028 economists, all of whom would eventually be in disagreement about how to exit the economic morass of the Great Depression, agreed on one thing - it would be a disaster if the bill were to pass.

They wrote to Hoover, begging him to veto the bill:

May 8th, 1930 Front page

Thomas Lamont, a partner at J.P. Morgan, would later recall: "I almost went down on my knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot Tariff. That Act intensified nationalism all over the world."

Henry Ford spent an evening at the White House trying to convince Hoover that the tariff bill would cause serious economic harm.

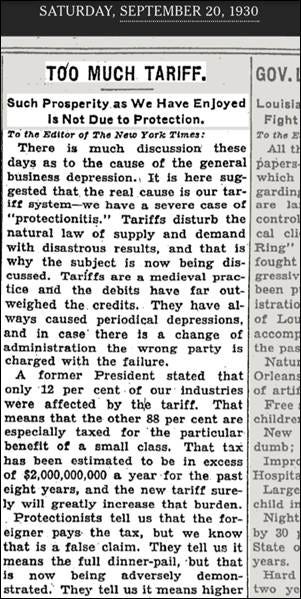

Yet, on June 17, 1930, he signed it anyway, because political suicide isn’t immediate, and sometimes that’s enough. The immediacy with which the tariff’s unpopularity grew can be seen in regular letters to the editor in the NYT:

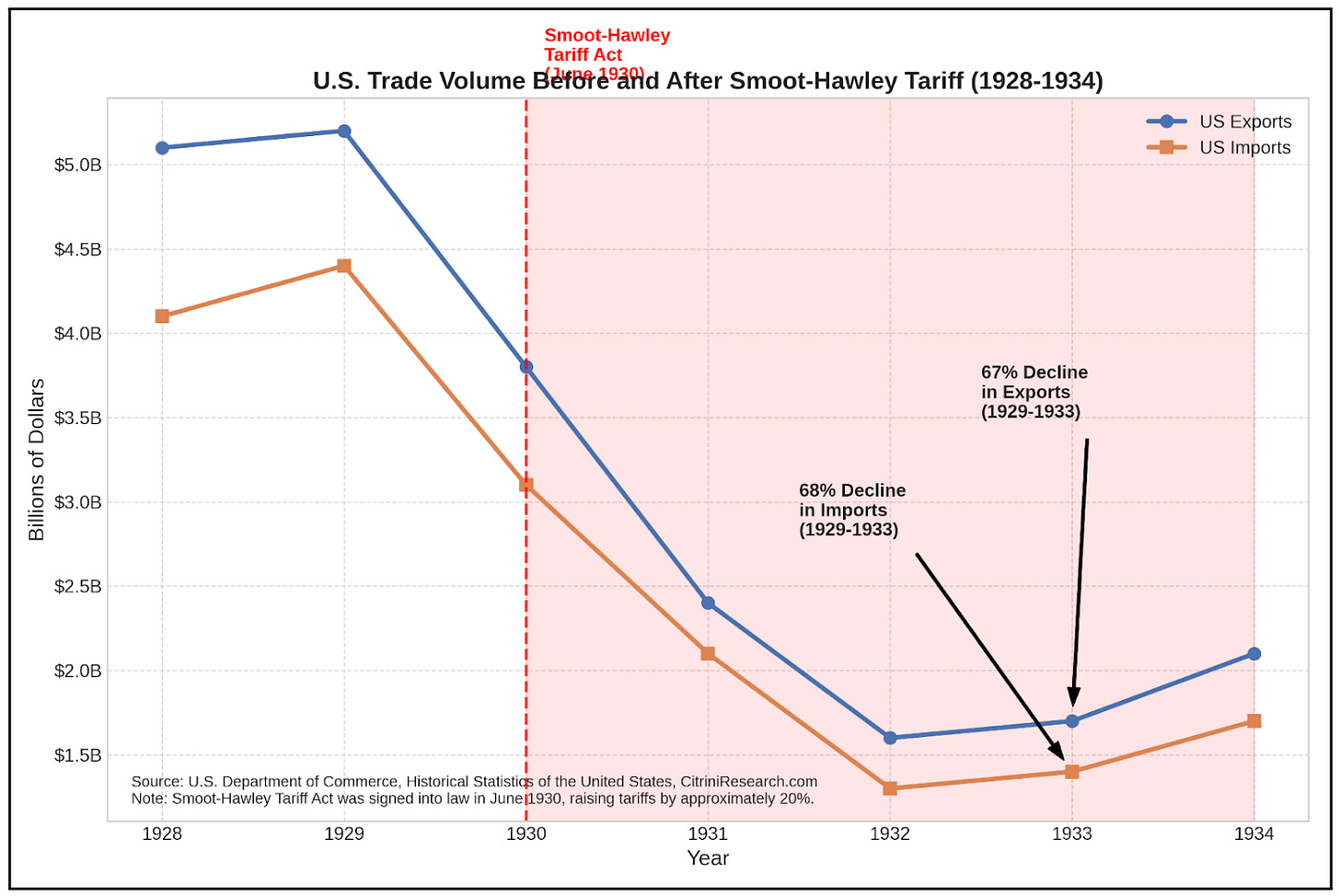

What followed was exactly what they said would happen: 25+ countries retaliated. Global trade collapsed.

U.S. imports fell from $4.4 billion in 1929 to $1.3 billion in 1932. Exports plummeted from $5.4 billion to $1.6 billion over the same period. World trade fell by roughly two-thirds between 1929 and 1934.

The 1929 crash set the stage for recession. Tariffs helped convert it into a depression.

What began as a financial shock turned systemic because policy — especially Smoot–Hawley — took a demand-side downturn and strangled it with a supply-side chokehold.

As economists had predicted, American consumers and businesses paid the price. The tariffs may have protected some jobs in specific industries, but they destroyed far more by making imported materials more expensive and closing off foreign markets to American exports.

The Democrats, recognizing the disaster, made tariff reform a key platform in the 1930 midterm elections – the first time they would control both houses of Congress since 1918. FDR said of Smoot-Hawley that it “compelled the world to build tariff fences so high that world trade is decreasing to the vanishing point”.

The verdict was clear: Smoot-Hawley had failed spectacularly.

Tariffs in 1922 vs. 1930: What changed?

You might be asking yourself at this point (you’re a real super nerd): “But why were the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariffs associated with an economic disaster and the 1922 Fordney-McCumber Tariffs not?”

First, the starting point: Fordney was imposed during a time of relative global economic growth, especially in the U.S. The Roaring Twenties masked many of its inefficiencies. Smoot–Hawley, in contrast, was passed after the 1929 stock market crash, during a period when global demand was already collapsing. It took a bad situation and made it worse. In the protectionist sense, tariffs are recession accelerants, but they still require a source of ignition.

In 1922, businesses and consumers were confident, credit was flowing, and financial conditions were loose. In 1930, you already had bank failures, significantly declining stock prices & contracting credit. Smoot–Hawley, with its significant increase in rates and broad swath (20,000) of covered goods, was heaped on top of this and signaled policy insanity at a critical moment, making investors pull back even more, fearing further protectionist escalations.

Second, retaliation. Fordney–McCumber triggered some limited retaliation (e.g. France in 1928, selective pan European tariffs), but global trade was still expanding in the 1920s. It's tempting to view Smoot-Hawley's damage in terms of its direct economic impact – raising the average American tariff on dutiable imports to 59.1%, a level reached only once before in 1830. But the true catastrophe wasn't the tariff itself. It was the global retaliation it provoked.

The Canadians, America’s largest trading partner at the time, had absorbed previous U.S. tariff increases without major retaliation. The 1922 Fordney-McCumber Tariff had raised duties on important Canadian exports like wheat, cattle, and milk, but Canadian producers had viewed these as tolerable reversions to pre-World War I levels.

Smoot-Hawley was different. It came during a deepening global recession when Canadian exports were already suffering. When King's Liberal government fell to Conservative Richard Bennett in the July 1930 election – just after Smoot-Hawley's passage – Bennett followed through on his campaign promise to "blast" Canada into world markets with tariffs of their own. Backing countries into a corner can result in their response becoming increasingly difficult to model.

In September 1930, Canada raised its tariffs dramatically on 16 American products that accounted for around 30% of U.S. exports to Canada. Not content with this, Canada also negotiated preferential trade agreements with other Commonwealth nations, further disadvantaging American exports.

The retaliation didn't stop with Canada. By 1932, at least 25 countries had enacted retaliatory measures against American goods. Spain adopted the "Wais Tariff" specifically targeting American cars and tires. Switzerland boycotted American products. France and Italy imposed quotas on American goods. Britain abandoned its historic free trade policy and enacted protectionist measures of its own. This caused a spiraling situation that lead to global trade freezing up in the face of uncertainty and consistently higher tit-for-tat trade policy.

Third, The State of Global Finance. In 1922, the U.S. was still a rising creditor nation, but the gold standard wasn’t fully re-pegged, and many countries were still restructuring from WWI. There was no tightly integrated global financial system yet. By 1930, however, the gold standard had been reestablished globally. International trade and debt flows were more interconnected.

Finally, from a symbolic perspective, Fordney was bad policy, but expected. Tariffs had been the norm in the U.S. since the Civil War, and Fordney-McCumber was viewed by many trading partners simply as a return to pre-WWI level. Smoot–Hawley, however, was seen as an escalation during a moment of obvious global fragility. It signaled the U.S. was turning inward at a time when it had cemented its status as a creditor nation. It undermined faith in global coordination and it may have helped trigger the abandonment of the gold standard by many countries shortly thereafter.

Markets and policymakers interpreted Smoot not just as a tariff, but as a worldview: isolationist, chaotic, and irrational. Uncertainty choked business investment.

A unique and unprecedented disaster of the protectionist trade policy era, it paved the way for the election of Roosevelt who promptly torched tariffs and passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act.

1934: RTAA - The Dawn of Reciprocity

After the protectionist disaster of Smoot-Hawley, American trade policy stood at a crossroads. The shift in power to determine trade policy from Congress to the executive branch that resulted in the move away from “Restriction” and towards “Reciprocity” began with the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934. This institutional change fundamentally altered how trade policy was made and allowed for the more liberal trade regime of the post-WWII era.

The story of modern international trade begins with Cordell Hull, a Democrat from Tennessee who would become America's longest-serving Secretary of State. Hull's journey from the agricultural South profoundly shaped his views on tariffs and trade. Unlike his northern counterparts who sought to protect manufacturing industries, Hull understood that high tariffs hurt agricultural exports.

Signing of the United States-Canada Trade Agreement. (Seated, L-R): Cordell Hull, W.L. Mackenzie King, Franklin D. Roosevelt in Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

1935-11-16

Hull's awakening to the international dimensions of trade came gradually. He later reflected that before Washington, he had "breathed in the fire of great tariff battles—but they were battles fought on the home grounds that high tariffs or low tariffs were good or bad for the United States as a purely domestic matter. There was little or no thought of their effect on other countries."

The RTAA emerged directly from the ashes of Smoot-Hawley's failure. Where that protectionist bill had triggered a cascade of retaliatory tariffs that throttled world trade, the RTAA offered a pathway back toward international cooperation. It introduced three revolutionary concepts that would define the Reciprocity era:

Executive authority: For nearly 150 years, Congress had jealously guarded its constitutional authority to "regulate commerce with foreign nations," resulting in trade policy captured by provincial interests. The RTAA transferred substantial negotiating power to the President, allowing tariff reductions of up to 50% without specific congressional approval for each cut.

Bilateral reductions: The Act enabled targeted negotiations with individual trading partners, creating a more strategic approach to trade liberalization and giving export industries a seat at the table alongside import-competing sectors.

Most-favored-nation clause: Any tariff reduction negotiated with one country would automatically extend to all countries with which the U.S. had commercial agreements, creating a multiplier effect that accelerated trade liberalization across the global system.

While initially focused on bilateral agreements, the Act created a template that would later inform the international trade architecture.

1947: Bretton Woods and GATT - Rules for a World on Fire

Source: Wikipedia/Wikimedia

As the guns of World War II fell silent, the architects of the postwar economic order gathered at a resort hotel in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods would lend its name to the system they designed—a framework intended to prevent the economic nationalism and financial instability that had contributed to the war they had just fought.

The Bretton Woods Conference of July 1944 brought together 730 delegates from 44 Allied nations for three weeks of intense negotiation. The conference reflected two competing visions for the postwar economic order. On one side stood the British economist John Maynard Keynes, representing a war-weakened Britain now dependent on American financial support. Across the table sat Harry Dexter White, representing the economic juggernaut that America had become.

Keynes proposed an ambitious "International Clearing Union" with a global currency (which he called "bancor") that would automatically balance trade and prevent the accumulation of excess surpluses or deficits. White's more conservative plan preserved national monetary sovereignty while establishing rules for exchange rate stability based on the U.S. dollar's convertibility to gold at $35 per ounce.

White's plan largely prevailed, though with important concessions to Keynes's concerns about adjustment flexibility. The resulting agreement established two critical institutions: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which would monitor exchange rates and provide short-term financing to countries facing balance-of-payments difficulties, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, now part of the World Bank), which would facilitate reconstruction and development through longer-term loans.

The Bretton Woods system represented a compromise between the rigidity of the pre-1914 gold standard and the chaos of the interwar currency wars. Countries would maintain fixed but adjustable exchange rates against the dollar, which served as the system's anchor through its link to gold. The IMF would provide short-term financing to countries facing temporary balance-of-payments problems, allowing them to adjust without immediately resorting to contractionary policies or competitive devaluations.

This was a system explicitly designed to prevent the disastrous economic nationalism of the 1930s. By providing liquidity and adjustment assistance, it aimed to give countries the breathing room to maintain both domestic economic stability and international cooperation. The architects of Bretton Woods understood that the choice between domestic economic objectives and international obligations had torn apart the interwar economic system. Crucially, the Bretton Woods architects recognized that monetary stability alone was insufficient.

A complementary framework for trade was needed. This came in the form of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947.

While the U.S. and Britain agreed on the bones of the system, they clashed over the cartilage. The U.S. wanted to eliminate British imperial preferences. Britain wanted deep cuts in U.S. tariffs, still bloated from the Smoot-Hawley era. The compromise? Make it multilateral. Dilute the politics and spread the pain.

Its core pillars:

● MFN (Most-Favored Nation): Every trade concession made to one member must apply to all.

● Tariff bindings: Once a tariff is cut, you can’t raise it without compensation.

● No quotas (mostly): Because nothing says “central planning” like a chicken import limit.

Over the next few decades, GATT rounds (Annecy, Torquay, Dillon, Kennedy, Tokyo, Uruguay) would chip away at global tariffs, converting an ad hoc postwar peace into a functioning world order. By 1994, GATT had become the WTO, and global average tariffs had dropped from 22% to under 4%. From the initial 23 founding contracting parties, it expanded to include most of the world's trading nations, overseeing a dramatic expansion of international trade in the postwar decades.

GATT’s genius was its simplicity. It treated tariffs like nuclear weapons: dangerous if used, contagious if retaliated against. GATT’s core principle was not that all trade is good but that any retaliatory protectionism is worse. It was a behavioral contract, in effect: No more weaponized tariffs. No more trade collapses. If you want to raise barriers, you pay. If you cut a deal, you share.

Because of this elegance, GATT proved surprisingly durable. For decades, it worked for one simple reason: everyone remembered what happened when it didn’t.

The Bretton Woods monetary system, however, proved less resilient. Faced with persistent balance-of-payments deficits and declining gold reserves, President Nixon suspended the dollar's convertibility to gold in August 1971, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates.

1971: The End of the U.S. Dollar’s Convertibility to Gold

From the Age of Exploration through the Colonial Era (roughly 1400 to mid-1900), gold and silver broadly functioned as the currency for settling international trade. Spanish silver dollars specifically were most often used for international trade settlement (and the term "dollar" has its etymology in a silver mine). Generally speaking, IOU-based fiat money systems could work well locally (where trust and enforcement were practical), but not internationally.

For example, during the Golden Age of Piracy, the Caribbean was a melting pot of European colonial empires (the British, French, and Dutch) all settling trade in Spanish silver dollars. The Spanish empire was the biggest source of silver and produced standardized, ubiquitous silver coins. Even on the other side of the world, China only accepted silver (and Spanish silver dollars specifically) in exchange for the tea it sold Britain.

Fast forwarding through a period where the British pound (gold-backed) was the primary reserve currency, the US became the world's largest economy during the American industrial revolution in the late 1800s and the recognized military superpower in 1944. And after 1971, it became the first true fiat-only global reserve currency. One way to think about it: in a winner-take-all network effect, the US dollar became and persisted as the dominant global reserve currency.

It’s relatively easy to see what that did to the U.S. economy:

Given that gold and silver deposits are scattered around the earth, metal-based currency systems, even the one under Bretton Woods, meant that no single country was the sole source of the global reserve asset. Under Bretton Woods (1944-1971), currencies were pegged to the dollar and the dollar was convertible into gold at a fixed rate. So, in addition to gold itself, the British pound and Swiss franc were also functional substitutes for the reserve asset.

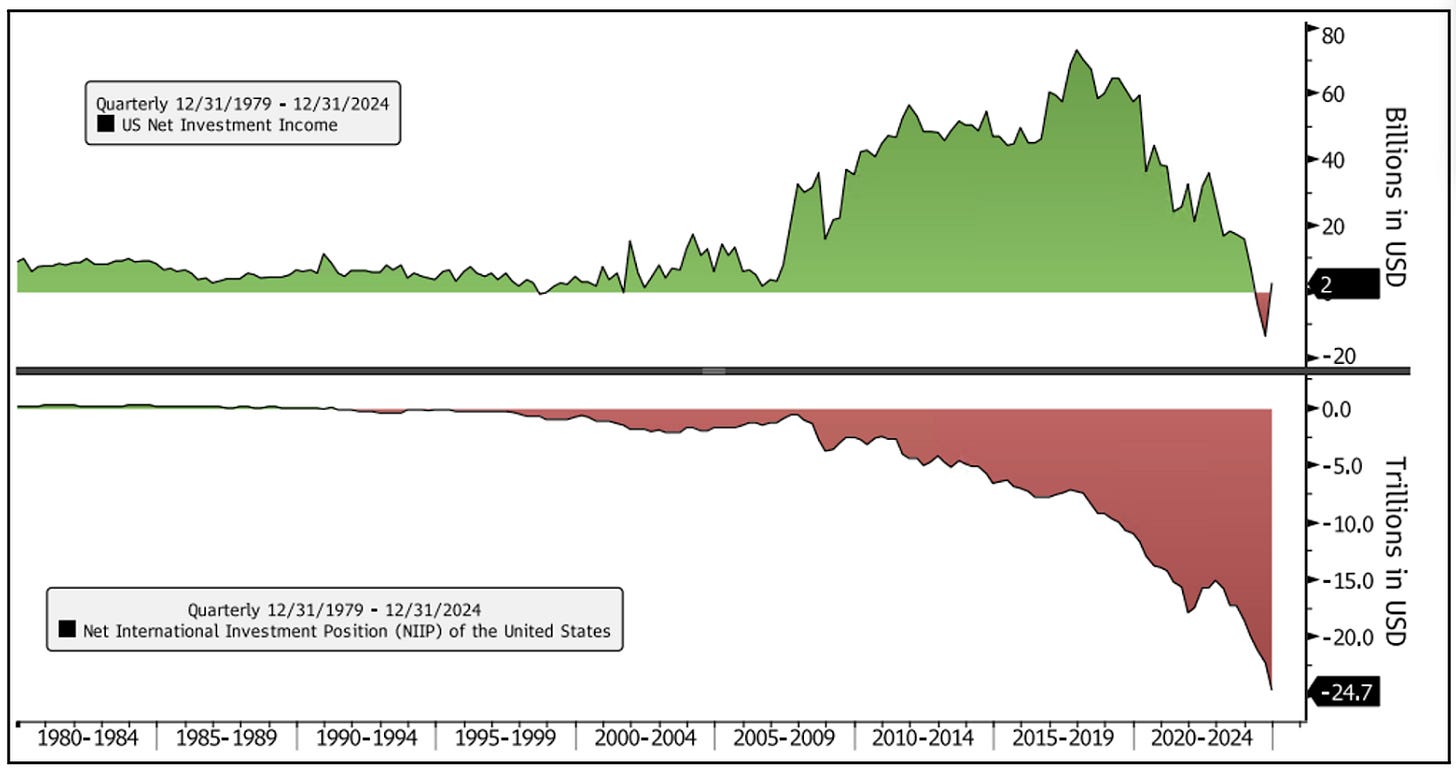

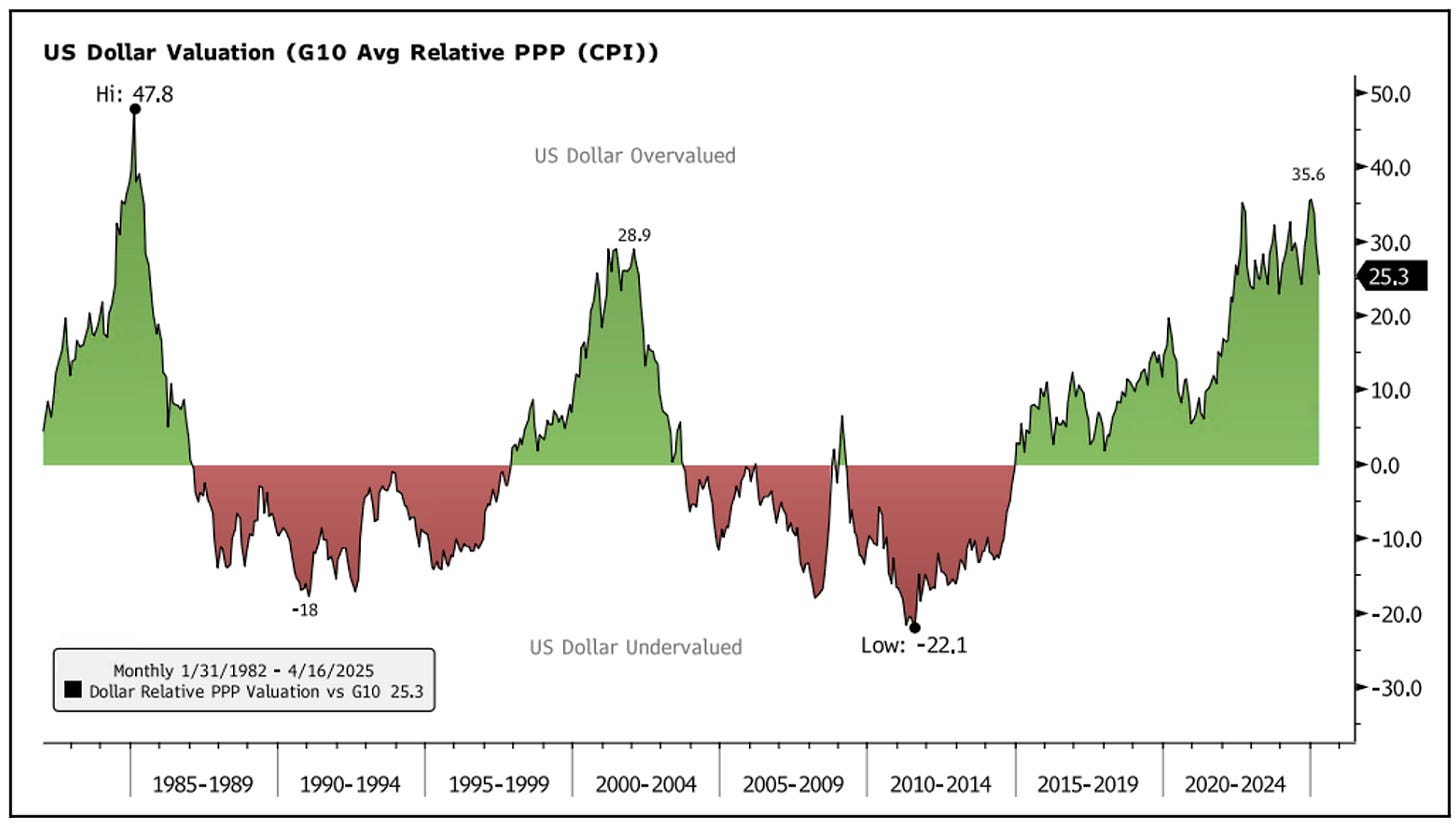

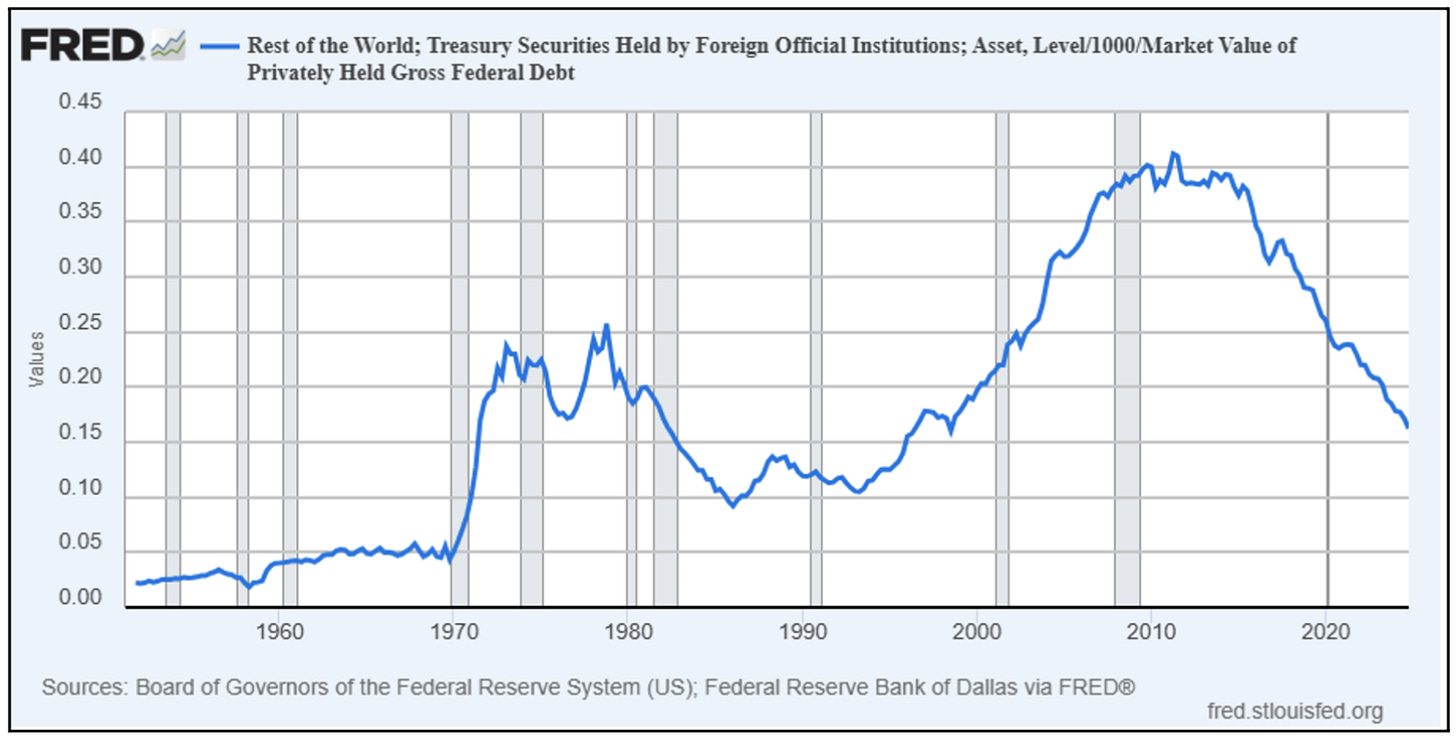

Somewhat counterintuitively, the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 solidified the US dollar’s world reserve currency status. As the sole source of the dominant reserve currency, the US eventually entered a dynamic of running persistent trade deficits to supply the rest of the world with liquid reserve assets. It’s counterintuitive because initially the US dollar was dismissed in favor of “the real thing” - gold. Volcker in the 1980s reasserted the dollar as the world reserve currency. In 1980, gold was no longer a one way bet versus the dollar. It was “exposed” as a volatile commodity prone to speculative booms and busts—not a stable store of purchasing power. Since the 80s, the US has had a hard time running a trade surplus (given the rest of the world’s natural desire to accumulate financial wealth denominated in the reserve currency).

The dollar’s reserve currency status has not been without benefits to the US, however. The “exorbitant privilege” concept means that while the rest of the world owns more US assets than the US owns in the rest of the world, the US actually makes more income off their overseas investments. That’s because a large portion of the US assets held abroad are in the form of high-quality, low yielding USD currency balances and fixed income securities (e.g., Treasuries, agency MBS, etc).

An IOU-style fiat system can work on the global level when there is international trust and enforcement (and it has for many decades), but the US hegemonic global order is now being cast into doubt–not by the rest of the world, but by the US itself.

How Could It Play Out From Here?

While the world has drastically changed since the post-WWII era of Reciprocity, the fundamental tensions that shaped America's tariff history remain. Today, we find ourselves at a similar inflection point to the ones that transformed trade policy in 1930, 1947, and 1971. Just as those moments were driven by shifts in America's position in the global order, today's tariff resurgence reflects another realignment of economic power. However, there's a critical difference: the U.S. is voluntarily disrupting the very system it created.

It’s time for the investing public to internalize a key insight - this isn’t going to be over in three months. Not in any appreciable sense, anyway.

Everything that the U.S. does in the next 90 days won’t be about relief or returning to a reasonable paradigm (i.e. 10% blanket tariffs and targeted reciprocity), it will be the first salvo. It will be focused on isolating China in an attempt to force them to the negotiating table. And if you’re not with us, you’re against us in that.

There exists 2-3 months worth of inventory in domestic US warehouses that can blunt or distort the initial impact of the hit to global trade. As that inventory runs dry, we’ll begin witnessing the genuine impact and second order effects of freezing up global trade. Reserve managers will continue to diversify away from the dollar, which has entered a secular bear market.

The tariff pause is a tactical gesture in ongoing negotiations, with no chance at permanent resolution with China over the next 2-3 months but backchannel progress made on European and potentially LatAm countries. The market read it as de-escalatory, but the reality is that it makes business conditions even more uncertain. To survive over the next 90 days, it’s imperative we have a good idea as to…

How do we understand how the administration is seeing things?

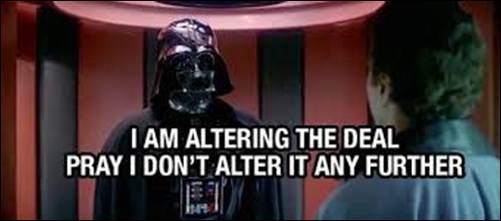

In this context, it is helpful to frame the view of the administration. As far as Trump is concerned, US hegemony and reserve currency status has been a raw deal for the U.S. - losing advantage in trade and manufacturing while simultaneously holding up the system of global trade “for free”. So, now, the US takes a stance that can more or less be summarized as:

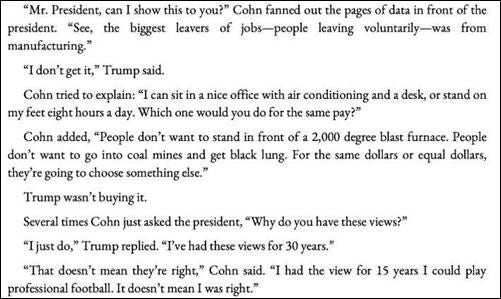

What’s extraordinary is not that tariffs were used, I don’t think anyone should be surprised by that fact. Trump has loved tariffs for decades, and if you’re surprised that “Tariff-man did tariffs” you should find a new occupation.

What is surprising is how all three R’s returned at once and yet they still don’t capture the full picture.

Revenue, in the form of billions in new federal intake that isn’t called a tax hike but walks and quacks like one.

Restriction, not just as an industrial strategy but as populist aesthetic — a wall, built at the port instead of the border, applicable to everything and anything. Unless I’ve missed exactly how we are protecting the American banana and coffee growers, the blunt nature gives this away.

Reciprocity, turned from a mutual easing of barriers into a scoreboard grudge match tallied in trade deficits.

Then there’s something else at play, something that’s not quite revenue but is unique to this implementation and the globalized world it is occurring in. There needs to be a fourth “R” to define the change that this seemingly simple increase in tariff rates represents. Because we aren’t really reverting to a previous dynamic, we’re charging into a novel one.

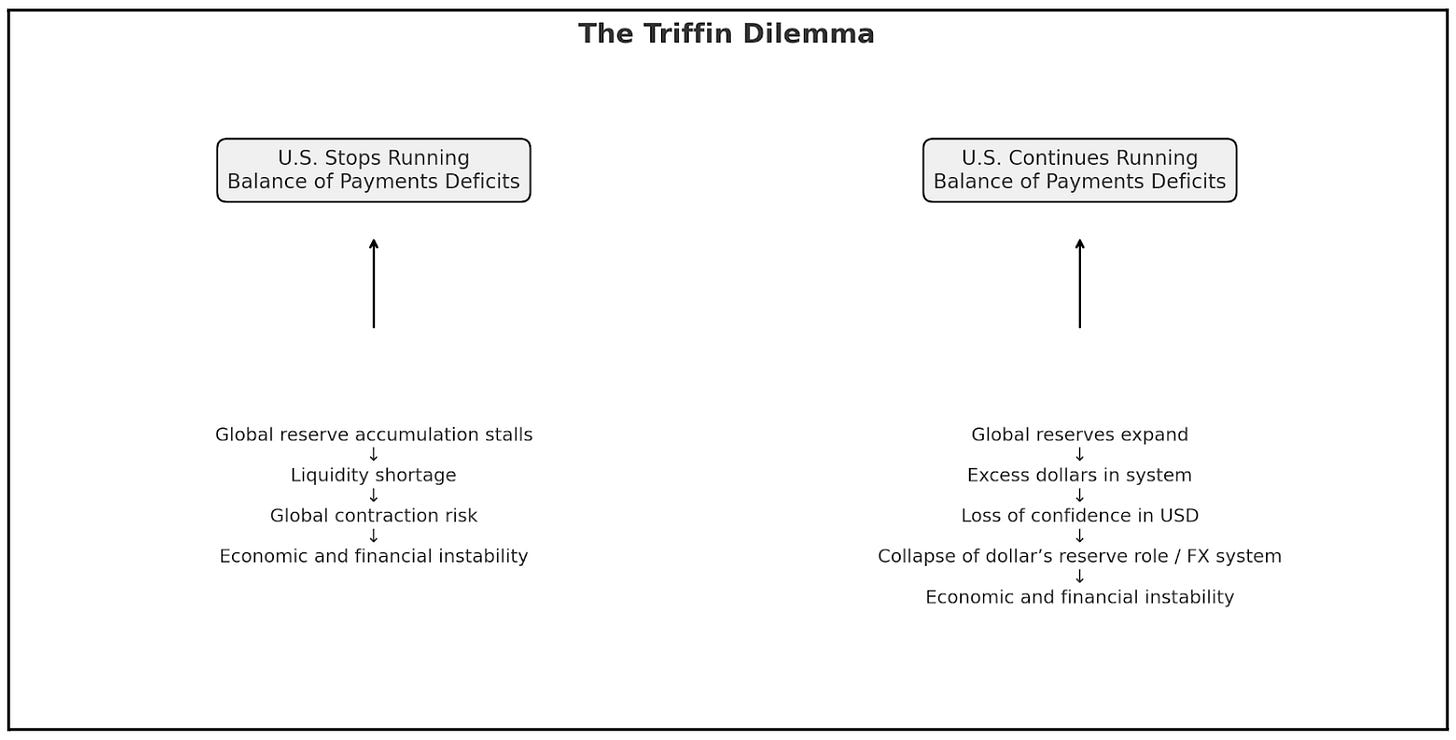

In order to do that, one must fully understand the administration’s point of view. We mentioned the challenges of attempting to rebalance global trade via targeting deficits with other countries in our piece two weeks ago (Seeing the Stag). The “Triffin dilemma” describes the paradox faced by a reserve currency country (and was applied back before the U.S. dollar’s convertibility to gold had ended). The paradox goes like this:

“Providing reserves and exchanges for the whole world is too much for one country and one currency to bear."

Henry H. Fowler

U.S. Secretary of the Treasury

The Trump administration’s take on the Triffin Dilemma is, predictably, less IMF white paper and more invoice. They feel the U.S. has been taken advantage of and forced to underwrite foreign trade surpluses, and they want to remedy that. Targeting countries with tariffs via their respective deficits is a good indication of where their priorities and concerns are.

FROM THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION’S PERSPECTIVE, what has happened/is happening in the existing system is:

Foreign central banks buy dollars not out of preference but obligation—because if you want to keep your currency down and your exports up, you need to hoard USD.

Those dollars get parked in Treasuries, which conveniently fund the same U.S. government that complains about being taken advantage of.

The dollar stays structurally overvalued, a direct byproduct of being everyone else’s savings account and lifeboat.

American manufacturing gets hollowed out, not because China cheats (though sometimes it does) but because the U.S. plays system administrator in a network it doesn’t fully control.

Eventually, the trade deficits compound, and Trump doesn't like the sound of the word “deficit” or the idea of being the world's biggest “debtor nation.” The reserve currency role begins being viewed as less of a privilege and more of a terminal liability.

Tariffs, seen through this lens, are not just about protecting factories or funding the government. They’re an overdue fee for system maintenance. In effect, they’re the geopolitical equivalent of being charged $14.99/month for a subscription you forgot you signed up for. Put even more simplistically, the administration’s view is

“We run the system — we moderate the flows, we secure the shipping lanes, we buy your exports, and we issue your reserve asset. Now we’re billing you for it.”

The Fourth R: Rent

Rent reframes tariffs not as a means to fund the state (Revenue), protect domestic producers (Restriction), or secure reciprocal access (Reciprocity), but as a fee-for-service model for global economic participation. This new paradigm is essentially…

Globalization-as-a-Service

Tariffs, NATO threats, mineral ultimatums, opposition to foreign acquisitions) are forming an intentional pattern: extract national wealth from foreign dependencies using whatever levers are available. Even if the lever is to blow up global trade and the USD’s reserve asset status.

Tariffs are a blunt tool, and it’s clear that Trump is using them as part of a broader negotiation in an attempt to upset this system. This is nowhere more evident than the tariff rate on China - 125%. With tariffs that high, trade simply stops. So why not use sanctions or quotas? Because it’s integral to start that negotiation from a place of “paying a fee”.

The negotiations during the 90 day tariff pause window could play out a few ways. The primary focus will be to form a coalition to force China to the table, but it might also be the case that we start to see talks about imposing this “fee” in a more sustained way.

How does the rent get paid?

The idea of a “Mar-a-Lago” accord is something I’ve been skeptical of, and I still think it’s extremely unlikely to play out. But, still, there is value in examining discussions. The proposed issuance of a century bond, rife as it is with potential for unintended negative consequences, is a good example of how the fourth 4 of “Rent” could work.

The idea is this: by issuing a 100 year duration treasury at a negative real interest rate and encouraging (forcing) countries to swap their existing longer duration holdings into this new issue, the U.S. can extract additional financial benefit from remaining the world’s reserve currency and facilitator of global trade.

While the impact would be unpredictable and likely chaotic, undermining US creditworthiness and wreaking havoc on the curve, the idea of offering to take tariffs off (or lower them significantly) on countries that agree to swap their treasuries into a 100 year duration bond that pays a negative real interest rate is something that Trump could be keen on. After all, he has spent his life restructuring and refinancing the debt of various Trump organizations.

This is just one example, and an unlikely one at that. Stephen Miran has recently expressed that he is not advocating for such an idea. But the fact remains that Trump is taking a sledgehammer to the existing international rules of the game and calling the role of the dollar and US treasuries into question. And why? Because he is solely focused on the impact of the existing dynamic on the U.S.’ coffers. This point of view risks missing the forest for the trees.

If the US effectively defaults on its foreign held Treasuries in a hostile century bond issue/swap, that will likely send gold higher and the dollar lower. The impact on the yield curve would be a sight to behold. Even without this scenario playing out, it seems clear there will be further diversification of official FX reserve assets, into gold, euros, francs, and yen. And that, potentially, deals will be struck to settle trade in currencies other than the dollar.

It’s unsurprising, when faced with this potential reality, that foreign official holdings of U.S. treasuries have been declining for years:

Current U.S. policy is prone to being viewed by other countries as extortionate. This kind of economic brinksmanship is inherently high-risk. In a failed implementation, it is kind of like the U.S. being both the bank and the customer taking a loan from the bank…and then deciding to default on itself.

But the fact remains: for now countries are stuck negotiating with someone ready to blow up the system, consequences be damned. It is not difficult to see how many countries could simply acquiesce rather than deal with the reality of a deglobalized world & hardship.

Is there an outcome to this that’s not devastating to the global economy? Yes, but there’s no outcome where global trust in the U.S. is restored with haste.

No matter how the negotiations go, it’s clear that trade policy is going to be the primary driving factor for cross-asset returns and economic growth this year. And it’s clear that we are witnessing a regime change that will have macroeconomic consequences for years to come.

In this new regime, tariffs aren’t policy as much as they are precedent. The U.S. has shown it will use market access like a dial, tightening or loosening trade conditions based not on economic efficiency, but on geopolitical compliance. Regardless of whether the administration proposes extensive tax cuts or other supportive measures, it will all come down to how and when US-China trade talks progress.

Nothing really matters more than that right now. China and the U.S. have already speed run the Smoot-Hawley retaliation spiral, up to 145%.

So, even if the situations and circumstances are drastically different, it’s easy to see how those desperate economists and bankers felt in 1930 watching the trade war of Smoot-Hawley unfold. Globalization has become a bit like economic mutually assured destruction. And, just like MAD, there can exist “winners”. Maybe one country is only 80% obliterated while the rest are totally gone. But is that really a world we’re hopeful for?

Unlike Hoover’s administration, the Trump administration faces the contradiction of being both debtor and trade restrictor. While both sought to maintain America's position through tariffs despite warnings from economists, Hoover's policy was a primarily defensive (and misguided) attempt to protect American industries, today's approach contains an additional offensive element: the deliberate use of the U.S.’ debtor status as leverage, turning the global trading and financial system from a public good into a private toll road.

And while it might be tempting to simply go back to the last time tariffs were this high and say “well, that will probably repeat”, there’s a problem with that.

The Return of the Tariff State?

This isn’t the 1890s or 1930. It is a world that’s become globalized and integrated and has never tried de-integration before.

We are not too far temporally removed from a situation that taught us a lesson about just how interconnected the world has become. The pandemic didn’t just disrupt, it revealed. It showed us, in stark relief, just how brittle the architecture of global trade had become. Ships stalled, semiconductors vanished, and the illusion of supply chain robustness shattered.

I don’t think we can just…unweave supply chains. Nor do I think America can tariff its way out of systems that were designed, over decades, to be just-in-time, just-in-place, and just-barely-resilient. Trump’s trade policy isn’t Smoot-Hawley, regardless of how many are tempted to compare.

The most uncomfortable part of this whole thing is that there is no historical framework. You can borrow from the 1970s and the 1930s and any other events that rewrote the plumbing layer of the system, but it’s not going to account for everything.

The world didn’t de-globalize in the 1930s, it had barely globalized to begin with. Now, for the first time, we are watching a superpower voluntarily jam a stick in the spokes of the very wheel it built.

And here’s the kicker: it may work. Temporarily. Politically. Until it doesn’t.

Just like Smoot–Hawley “worked” for about three months - - until Canada retaliated, Europe rearmed its tariffs, and global trade fell into a trapdoor. Until U.S. farmers went bankrupt in record numbers while still voting for the men who doomed their prices.

Today’s tariffs are different only in form, not in function. The same belief animates them: that you can produce stability by disrupting complexity. Unfortunately, complexity isn’t going to go down without a fight.

Let’s be honest: no one fully understands how our complex, multivariate global system functions in real time. Not the Fed, not CEOs, not the IMF and, sure as shit, not me or you. The ripple effects are impossible to comprehend. On the course we’re on, however, it seems we will be increasing our collective understanding in the most uncomfortable way possible.

Which raises a blunt question:

How does a company commit to a 30-year, capital-intensive investment in a world where the rules might change next quarter?

Where tariffs aren’t policy but vibes subject to the next tweet (or, “truth” I guess), the next election, the next populist wave?

This isn’t just a trade problem. It’s a capital formation problem. Long-term investment can only exist under a rare combination of circumstances: predictability and trust in institutions being the primary two.

While U.S. markets have proven remarkably resilient; through world wars, depressions, stagflation, tech bubbles, and Twitter-driven bank runs, that resilience wasn’t accidental. It was built atop a rare and volatile mixture of ingredients that most nations never manage to assemble, much less maintain over decades.

Start with global trade. The U.S. has been the central node in the world’s commercial web for nearly a century—not because it produces the cheapest goods, but because it provides the deepest markets, the most trustworthy currency, and the broadest consumer base. Trade has been the silent partner of American prosperity, enabling the country to import low-cost goods, export high-value services, and recycle global surpluses into domestic assets.

Then there’s political stability. Say what you will about polarization and the follies of a two-party system, but the peaceful transfer of power every four years and the predictable continuity of contracts, courts, and governance has given capital the confidence to stick around. Investors may hate regulation, but they hate chaos more.

Add in a robust legal and regulatory framework. Property rights. Bankruptcy courts. Enforceable contracts. These are the dull, technocratic plumbing of capitalism, but without them the capital doesn’t flow.

On top of all this, of course, there’s the dollar. The reserve currency status of the U.S. has created a kind of gravity well for global capital. Foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, multinational corporations: all of them keep reserves, settle trades, and manage risk in dollars. That demand suppresses borrowing costs and gives the U.S. an unparalleled ability to run deficits without immediate consequence.

And finally, there’s luck. Two oceans, a vast network of rivers and navigable waterways, natural harbors, agricultural perfection, no hostile neighbors for a century and a half. Massive natural resources. A demographic boom when it mattered most. A continent-sized internal market. If you were designing a country for hegemonic success, you’d start with a map of America. The U.S. has been quite lucky, to say the least.

The system may look sturdy from the outside but it is, in fact, intricate and interdependent—an equilibrium held together by geopolitical necessity, norms, incentives, and a kind of polite collective delusion that tomorrow will look roughly like today. Massive shifts to the plumbing of the system are the only geopolitical events that don’t result in a “buy the dip” moment but rather protracted periods of volatility - 1971 being a prime example.

And so, we return to the foundational question, and one that we will soon all have an answer for.

What is the cost of unpredictability?

The honest answer: I don’t know. I don’t think anyone does. But the system can only take so much of it, there is a line that, once crossed, cannot be undone. The good news, perhaps, is that the U.S. still retains more leverage than any other country in the world. That is, unless they team up or are willing to endure more pain than has been planned for by the Trump admin.

Nicely done. I remain skeptical that anything resembling a grand plan will come out of this. Negotiating credibility is mostly gone, political will for a protracted period of economic pain is not there, and this is the second-term project of a lame duck with a thin congressional majority and no strategic allies.

Great piece. But it begs the question - how do we position for this? It seems everything is "bad" under this scenario?